By Aaron Wolf

Questions

How has war affected the history of Tehran? Are its marks visible? How have the techniques of modern warfare—including terror, broadly defined—shaped the city or urban policy?

Discussion

Over the course of Tehran’s modern history, several conflicts have had a significant impact on the city both socially and physically. Tehran gained status as a legitimate town within the Safavid Persian Empire in 1554 when Shah Tahmasp I led the construction of the bazaar (marketplace) and first city walls, but it was nothing more than a small, nationally insignificant place until the late 18th century when the founder of the newly ascendant Qajar dynasty, Agha Mohammad Khan, chose it as his capital (Bosworth et al, 2007; Khosravi, 2008). Since that time, several major events within Persia, and later, Iran, have shaped Tehran into the metropolis it is today. With a focus on the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s, this report will demonstrate how these impacts of war have been both direct and indirect, affecting both the physical shape of the city and the psychosocial condition of its residents.

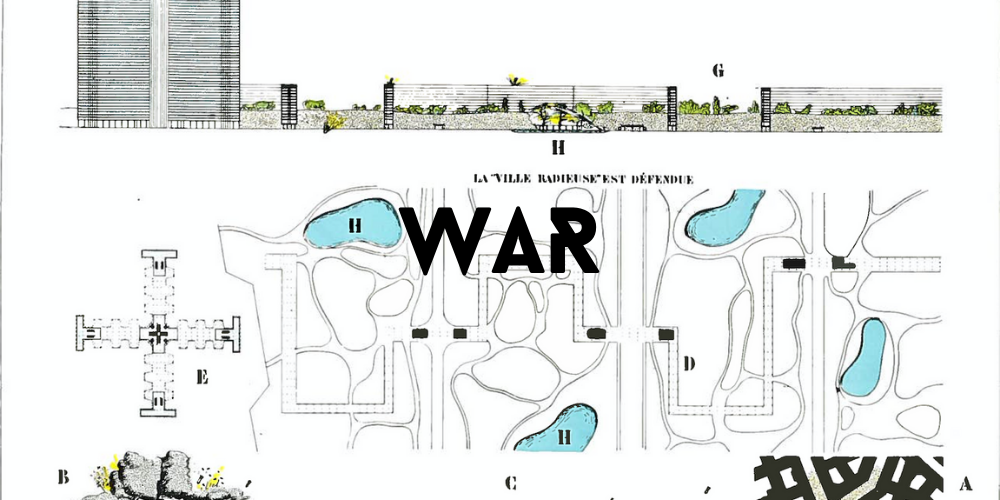

By the mid-18th century, population growth within the city had rendered the original rectilinear enclosure surrounded by city walls obsolete. In fact, by the 1860s, one out of every ten Tehranis lived outside the city walls. At the same time, the ruling Qajar dynasty was struggling both in terms of its political leadership and its military strength. Persia had fallen victim to major defeats in three wars with the British and Russian empires over the course of the early-to-mid-19th century, leading to both embarrassment for its governing body and large swaths of lost territory. After being trounced in these conflicts, Persian leadership, headed by Naser al-din Shah, sought to modernize the empire and this large-scale modernization effort reached the capital. Following the first town-planning initiative in the 16th century, a second one took place from 1868 to 1880, which Madanipour describes in his 2006 article covering the Tehran’s major urban developments. Influenced by European architectural and city planning experts, Tehran erected new city walls in an octagon shape. These walls expanded the city’s land area to accommodate the growing population and helped bring Persia’s capital into a new age.

The purpose of these walls was less defense than it was growth management and tax collection. Although many cities around the globe at the time were doing away with walls altogether, keeping the city’s population within a defined, compact area allowed for easier urban administration (Madanipour, 2006). In this way, Tehran’s 19th century expansion represents one channel through which war can accelerate urban development, albeit indirectly, as military defeats triggered modernization efforts, but not in a way that directly addressed military shortcomings.

War has also had immediate and direct effects on Tehran, and this was manifest to an extreme extent with the Iran-Iraq War. The war was a long and brutal conflict fought to alter the balance of power between the two Middle East countries, and directly caused by both border disputes and fears of a similar revolution in Iraq to the one in Iran in 1979. The impact of the war on Tehran’s inhabitants came to a head in its final stages, which McNaugher describes in his article on the use of deadly weapons to end the war. As part of the so-called “war of the cities,” the two states exchanged aerial attacks on each other’s major urban areas in 1988. During this time, Iraq used chemical weapons on Tehran and launched 160 extended-range SCUD missiles against the city over a seven-week period. The psychological impact these attacks had on people in Tehran and other major Iranian cities was a major factor in bringing an end to the war (McNaugher, 1990).

It should first be noted that Iran was suffering from an overall decline in morale amongst its soldiers and citizens before the “war of the cities” was initiated. The republic’s military success in the war had plateaued after February 1986 and Iraq was growing in international support. At the same time, Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini’s government was struggling through an economic and political crisis, in part due to its failure to accept a UN-brokered cease-fire agreement in July 1987 which was unquestionably favorable to Iran (McNaugher, 1990). So, while the scale of the bombing of Tehran was not enormous, in the context of other morale problems, the attacks exacerbated the psychological effects of war for a military force and urban populace that probably knew the war could not be won.

The type of weapons used on Tehran was also a major factor in generating the psychological effects and visible panic that led Khomeini to finally accept a cease-fire in August 1988. Unlike more predictable bombing raids, ballistic missiles can strike at any time without warning, and as a result, tend to be more demoralizing for their victims. Chemical weapon attacks also tend to be more disturbing visually than other types of weapons, producing a deep psychological impact even if fatalities are minimal (McNaugher, 1990). In this sense, the direct impact of the final months of the Iran-Iraq War on Tehran’s citizens and soldiers was so powerful that it became a major factor in pressuring Iran’s leadership to bring the eight-year conflict to a close.

On top of the immediate psychological impact that the war had on Tehran, there were also lasting effects for the city’s residents, which Ehsani illuminates in his article on the war’s refugees. The war created tens of thousands of refugees in areas throughout Iran and compounds were established across the country to shelter and protect refugees for the remainder of the conflict and often for long afterwards (Ehsani, 2017). Some of these compounds were in Tehran, including Shahrak-e Fajr, which sheltered 700 households during the war (Ehsani, 2017). Conditions for wartime refugees were theoretically supposed to be better in Iran than in other countries, especially considering that in Iranian society, families of fallen soldiers are meant to be treated with respect. Martyrdom is considered the highest representation of the moral legitimacy of the republic, and the war left approximately 200,000 widows and orphans of lost soldiers (Ehsani, 2017). Despite this, Iran-Iraq War refugees in Tehran suffered through miserable conditions for extended periods of time. The hostels suffered from material deprivation and overcrowding. Additionally, women in the compounds were victim to severe moral policing, as officials feared the single women would initiate relationships with strangers considered inappropriate or turn to prostitution to make their lives in the hostels more tolerable. The children who grew up in these places were particularly shaped by the insular culture and persistent propaganda (Ehsani, 2017). Once these families were finally able to depart the compounds, they were often stigmatized as poor wards of the state and it was difficult for war widows to remarry because their families viewed no potential new husband as equal to the one who was martyred. In Ehsani’s article on the subject, he writes of a “double displacement” for the refugees: first due to the war violence, and then due to the difficulty of returning home, as finding work was nearly impossible (Ehsani, 2017). Many of these refugees were forced to settle permanently in Tehran, significantly increasing the urban poor population. In this way, the social impact of the war on Tehran’s citizens endured long past the cease-fire of 1988.

The long-term impact of the Iran-Iraq War on Tehran as an urban area is reflected in the city’s immense growth in its aftermath. Refugees from the war, in addition to other migrants and refugees from conflicts in Afghanistan, drastically offset any decreases in population caused by city bombings during the war. In 1966, the population was 3 million, but by 1986 it had ballooned to 6 million due to both war displacement and the promise of low-cost housing provided by the state (Madinipour, 2006). The change in the land area within municipal boundaries was even more pronounced, tripling from 1980 to 1992 (Khosravi, 2008).

As demonstrated, war has had an enormous impact on Tehran in a variety of ways. In the 19th century, major military defeats prompted Persian leadership to modernize the capital, fundamentally altering the city’s shape. In the late 20th century, the Iran-Iraq War had both immediate and lasting consequences for Tehran’s residents. Aerial assaults on the city exacerbated morale problems to the point that the Iranian leadership finally accepted a cease-fire to end the conflict. In the long-term, refugees in the city were forced to suffer in meager living arrangements for years after the war. This influx of migrants also drastically increased both the population and land area of the city, forming one of the world’s largest metropolises.

Sources

Bosworth, Clifford Edmond, Minorsky, V., Calmard, J., & Hourcade, B. “Tehran.” In Historic Cities of the Islamic World, edited by Clifford Edmond Bosworth, 503–520. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill, 2007.

Ehsani, Kaveh. “War and Resentment: Critical Reflections on the Legacies of the Iran-Iraq War.” Middle East Critique 26, no. 1 (2017): 5-24.

Khosravi, Shahram. Young and defiant in Tehran. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Madanipour, Ali. “Urban planning and development in Tehran.” Cities 23, no. 6 (2006): 433-438.

McNaugher, Thomas L. “Ballistic missiles and chemical weapons: The legacy of the Iran-Iraq war.” International Security 15, no. 2 (1990): 5-34.