Questions

In what circumstances did facilities and entertainments for travelers first appear in Paris? When did people begin to come to Paris just to look at it, or at some particular place in it?

Discussion

The Paris of the present is a city built on tourism. Easily one of the most visited cities in the world; over 18 million people foreigners in 2018. That is not counting the many people in other regions of France who travel to Paris as well. Tourists spent over $17 billion dollars in Paris during their visits. It is estimated that 260 thousand workers, or 20 percent of Paris’ workforce, are employed in tourism related sectors, be it hotels, leisure, catering, and transport. How did tourism become such an established part of Paris’ economy and how did Paris become an established destination for travelers the world over?

Paris, as the longstanding capital of France, was always a destination of sorts, but not necessarily because it was a nice or fashionable place to be. In the 18th century, when urban renewal efforts began, they coincided with the rise of the Paris salons and an image of intellectual brightness that attracted people to the French capital.

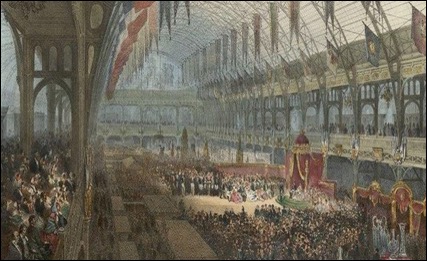

The reconstruction of Paris began in earnest with the reign of Napoleon III and the Baron Haussmann. Napoleon sought to imitate the more urbane image of London. He believed the French Empire needed a capital worthy of the importance of being the center of an empire. Among the things he imported from London was the Exposition. (De Moncan 34) In 1851 London held the first World Exposition which showcased the evolution of London into a modern city and the ingenuity of the British Empire. Not to be outdone, Napoleon III decided to host the 1855 Exposition in Paris and managed to attract over 5 million visitors over the duration of the Exposition (Ageorges 21). While ticket sales were meager compared to the cost of putting on the Exhibition, it was a worthy start to Napoleon’s plans for Paris.

A total of four more Expositions were held in Paris in the 19th century, each one grander and more expansive than the last, and each one regaled world travelers with a city that was closer and closer to realizing its final design. The 1867 Exposition was the first one after many of the reconstructions of Haussmann and Napoleon III were completed (De Moncan 79). What is now known as the 2nd Empire Style of architecture dominated Paris. Visitors could stroll down wide boulevards and avenues. Many of them arrived in Paris by way of the grand train terminals constructed around the center of the city. The 1867 Exposition was attended by a number of foreign leaders. Dignitaries including the Tsar of Russia, the Emperor of Austria, the King of Prussia and Otto von Bismarck, and even the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire attended the Exposition at various times (Allwood 37).

Paris was rebuilt for the 1867 Exposition, and then rebuilt again for the 1878 Exposition. The 1878 Exposition was the first to occur after the Franco-Prussian War which included the destructive siege of Paris. The subsequent Paris Commune uprising damaged large areas of the city and stained the streets with blood. The 1878 Exposition notably featured the completed head of the Statue of Liberty which was later shipped off to the United States. Both Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell traveled to Paris to show off inventions (Ageorges 77). 1878 was also notable because it showed how Paris was becoming a city where standards were debuted and set. Victor Hugo led a standardization of international copyright law. A separate committee standardized international mail circulation. And the International Congress for the Amelioration of the Condition of Blind People adopted braille as a reading language for the visually-impaired (Allwood 93). The Exposition did not necessarily plan this, these groups and people took advantage of the large numbers of people coming from abroad to the expositions to hold concurrent meetings to address these longstanding international issues.

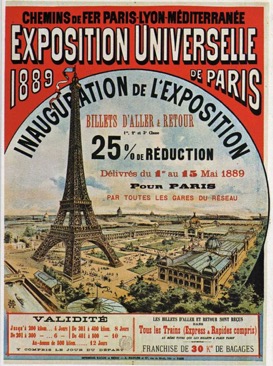

The most well known of the Parisian Expositions is the Exposition of 1889. The 1889 Exposition saw the construction of the Eiffel Tower. By the time of its completion it was the tallest tower in the world, although this was not appreciated by the local populace, who had grown attached to their low-rise city (Alexander 85). Nevertheless, the Eiffel Tower remained standing and since then has become the enduring symbol of Paris and France at large, even if today it is only the third most visited site in Paris after Disneyland Paris and the Louvre museum. Nearly two million people climbed the Eiffel Tower during the Exposition (NYT) and three times that number visit it each year today.

The Exposition of 1900 was the culmination of a half-century of changes in Paris. By this point the renovations of Paris along the plan of Baron Haussmann were almost entirely complete (De Moncan 104). Paris had cemented its image as a global city, worthy of attracting international crowds, worthy of being the imperial capital that Napoleon III had once sought. The 1900 Exposition sought to highlight France’s empire by creating miniaturized villages modeled after those found throughout French territories abroad, a human zoo, essentially (Alexander 108). The Exposition also showed a city on the cusp of modernity by showcasing the first stations of what would become the Paris Metropolitan Railroad (Metro), then one of the first subway systems in the world. The Lumiere brothers showed off their art of projection at the Exposition; the basis of modern film. The Grand Roue was Paris successful attempt at creating an even bigger version of the Ferris wheel which debuted at Chicago’s Exposition several years earlier; it stood over one hundred meters tall (Ageorges 112). Notably, the Paris 1900 Exposition also coincided with the 1900 Olympic Games, their second iteration, which were also hosted in Paris. All told, nearly fifty million people visited Paris that year for the Exposition and Olympics (Alexander 120).

Through all of these grand expositions, Paris slowly established itself as world-class destination, culminating in 1900. By this point the reconstructions of Haussmann which were once new were now historic, and the organized city had grown into its design. Paris has remained one of the world’s preeminent destinations to this day, with tourism, as previously mentioned, being a core section of the economy. The romanticism around Paris has only grown, so much so that there is sometimes a disappointment people feel when they visit: “Paris Syndrome,” it is called. It is the incongruence between the Paris that is seen in pictures and film and other media, and the Paris of the real world. When one steps off the train one might sniff the slight smell of urine rather than perfumed air. One might be harassed by a pickpocket while looking over the city from the hill of Montmartre (this writer has experienced both of these). For a city as trafficked by tourists as Paris, it can sometimes be hard to remember that Paris is still a city, and people live there, and Paris has all of the same ills that plague other cities, including poverty and homelessness, social unrest, and crime. It is the capital of France and ever the subject of politics and demonstrations. Nevertheless, the engine of tourism hums on.

Sources

De Moncan, Patrice. Le Paris D’Haussmann. 2002

Allwood, John (1977), The Great Exhibitions, Great Britain: Cassell & Collier Macmillan Publishers

Jullian, Philipe (1974), The Triumph of Art Nouveau: Paris Exhibition 1900, New York, New York: Larousse & Co

Ageorges, Sylvain (2006), Sur les traces des Expositions Universelles (in French), Parigramme

Alexander C. T. Geppert: Fleeting Cities. Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe, Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

The Commercial Cable From Our Own Correspondent. Copyright. “The Great French Show; What The Present Visitors Can See. The Eiffel Tower And Edison’s Exhibit–American Pictures Very Attractive–Other Matters.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 19 May 1889, www.nytimes.com/1889/05/19/archives/the-great-french-show-what-the-present-visitors-can-see-the-eiffel.html.