Questions

How has war affected the history of Osaka? How has the city been shaped and changed by war?

Discussion

The ports of Osaka are typically presented monolithically as historically continuous and successful spaces. Today, the port of Osaka is presented as a bustling hub for marine trade and business. It was once home to the Dojima Rice Exchange, where rice rates were established and rice distributed to the rest of the country. Today it also houses the Asia and Pacific Trade Center, a large international trade complex and shopping mall. It is also home to the former Japan World trade center—now Osaka Prefecture Government Sakishima Building or Cosmo Tower. Generally, its history with war has been glossed over. In truth, however, war or the threat thereof is intrinsically connected to the very existence of Osaka and its ports. Throughout its history Osaka has had drastically different experiences of war. Famously, Osaka Castle, which is a major city attraction today, was built as a military stronghold and as such, has been targeted militarily and burned down multiple times in conflicts over the course of time. However, Osaka’s earliest experiences with war go much further back in history, beginning with the very earliest projects for its development.

1614 Siege of Osaka Castle. (Wikimedia Commons)

Dojima Rice Exchange: Woodblock print by Hiroshige (1797-1858). (Osaka Prefectural Nakanoshima Library)

Today Osaka is referred to as the “Manchester of the Orient” and “Japan’s Kitchen” because of its central role as an industrial port city. These are relatively recent monikers, beginning in the Edo and Meiji era (Mizuuchi 107). Before Osaka was a bustling hub, it was an undeveloped natural port, prone to flooding. Osaka’s historical importance to Japan is essentially derived from its importance as a port, but its existence as a successful port is based on war. Towao Sakaehara—a literary scholar and researcher specializing in ancient Japanese history— demonstrates in “The port of Osaka: From Ancient Times to Today” that the inception of one of Japan’s most influential and successful ports surprisingly starts on the Korean peninsula. Initially, the ports of Osaka were developed between the 5th and 8th centuries by the Wa dynasty (Yamato Clan) due to concerns over events on the Korean peninsula. In 427, King Chongsu of the Koguryo kingdom in Korea moved his capital to Pyongyang and, following his father’s legacy of southward expansion, invaded and captured the Paekche kingdom. As Sakaehara explains, the Yamato clan, which held central control of Japan at this point, had a close relationship with Paekche and saw their defeat, followed by increased tensions on the peninsula, as a cause for concern. It was decided that the best course of action would be military fortification. Thus, Sakaehara concludes, after the excavation of a major canal, Osaka became intrinsically connected to the Yamato lands; giving Osaka an advantage over more strategically located sites like the Tsushima Islands or Kyushu when it came to selecting a location for the Yamato clan’s large war supply storehouses (Sakaehara 4-7). Essentially, it was Osaka’s ties with the Yamato clan and their growing concerns over recent and brewing military conflicts that first allowed for its growth into military, political and economic prominence.

Osaka’s underlying connection to war only continued as the port was further developed and used for military and diplomatic missions. Diplomats from Korean and China were housed in Osaka and diplomatic missions were always sent from there. Additionally, the Yamato clan’s navy when heading abroad was said to have always stopped by the port before heading out to sea (Sakaehara 8). With its established national importance encouraging ships to call into port so frequently, Osaka was able to grow into a flourishing and prosperous port. And while the port had eventually lost its national importance by 784 due to its lost capital status and the development of new river canals that bypassed Osaka –then Naniwa-zu (Sakaehara, 9), once again war would into the picture to revitalize the port and modernize it. In the 20th century, during WWI, the ports of Osaka thrived (“City of Osaka Port and Harbour Bureau Outline”) . Not being directly involved in the war, Japan was able to take advantage of the increased global need for shipping hubs, and Osaka experienced increased trade and thrived as a national transportation hub. The money made during this period allowed the region and the nation to thrive and subsequently helped fund Japan’s incursions and military endeavors abroad on the mainland and throughout Asia (Sakaehara 14).

Bomb damage in Osaka, 1945. (Library of Congress)

Osaka’s experience of war has not always been positive, of course. As previously mentioned, the Osaka Castle and, by extension, the city, have been burned down and required rebuilding after wars, military incursions, and peasant uprisings. Perhaps none of these, however, destroyed the city and its port like the bombings of WWII. The city and its port were bombed starting on March 13th and 14th; on several occasions throughout June and July; and even up until the war’s final days on August 14th (“1945”, pg.647-739). As most of the buildings in Japan were built almost entirely out of wood at the time, in contrast with European cities that were reduced to rubble, fire raids left the city almost completely leveled; leaving little more than smoldering ash (Diefendorf 186). With the damage and thus fewer ships calling into port, the city government had a major problem on its hands.

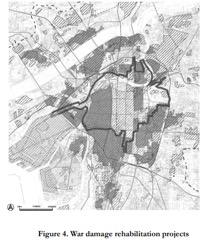

The city, however, was able to use the destruction to its advantage. They developed the Osaka Port Reconstruction Plan (“City of Osaka Port and Harbour Bureau Outline”) and as Jeffery Diefendorf states, Osaka city planners took rebuilding the city as a chance to improve it and “used the opportunity created by reconstruction to raise the level of the harbor area” Diefendorf 186). Despite local protests, the government was then able to reclaim large portions of privately owned land through the Port and Harbour Law (Ports and Harbours in Japan). According to Mizuuchi, 40-50% of privately owned land was appropriated for a 1949 land redevelopment project partially meant to rebuild the port from the war damage but also meant to build up defenses against natural disasters that plagued the port and surrounding region Mizuuchi 110-11). Ultimately the destruction of Osaka’s ports during WWII offered Osaka city planners a chance to do what few city planners abroad had been able to accomplish, which was to almost fully redevelop and expand the destroyed port.

Constructed, destroyed, and reconstructed time and time again as a military resource, Osaka and its ports have played a pivotal role in Japanese history and continue to be a major urban center, but it has only been able to function as such due to its innate connection to war and conflict. Ultimately, through exploration of Osaka’s history, one can see that the city and the port that allows it to thrive today are intrinsically tied to war and conflict. Osaka has a long history; from its origin as a war supplies storehouse with strategic access to the Korean peninsula, through its success as a major transportation hub in the early modern and modern periods, reaching a peak during WWI, to its complete destruction and expansive rebirth after WWII. Since its inception, the port of Osaka has not only been a historical strategic stronghold but also a pivotal place for military funding and conquest, in the archipelago and beyond.

Sources

“City of Osaka port and harbour bureau outline” (n.d). Retrieved from City of Osaka Port and Harbour Bureau, May 4, 2020. https://www.city.osaka.lg.jp/contents/wdu020/port/bureau/b_outline.html

Diefendorf, J. “Wartime Destruction and the Postwar Cityscape”. In War and the Environment: Military Destruction in the Modern Age, Edited by Charles E. Closman, 171-92. Texas A&M University Press, 2009.

Mizuuchi, T. “Postwar Transformation of Space and Urban Politics in the Inner-ring of Osaka”. In Critical and Radical Geographies of the social, the Spatial and the Political by Toshio Mizuuchi 107-131. Osaka City University, 2006.

Sakaehara, T. “The port of Osaka: From ancient times to today”. In Port cities in Asia and Europe by Arndt Graf and Chua Beng Huat, 3-18. Routledge, 2008.

“1945”. In The Army Air Forces in World War II: Combat Chronology, 1941-1945, Compiled by, Kit C. Carter and Robert Mueller, 584-733. Center for Air Force History, 1991. https://www.afhra.af.mil/Portals/16/documents/Studies/101-150/AFD-090529-036.pdf