By Jane Hutton

Questions

Where do the poorest residents live in Johannesburg? How did they get there?

Discussion

Ferreira’s Gold Mine in Witwatersrand in 1886.

When gold was discovered on a farm on the Witwatersrand in 1884, it initiated the gold rush that led to the founding of the city of Johannesburg. As Susan Parnell describes in her doctoral thesis, the migrant workers that constituted most of the mining workforce were generally housed in compounds close to the mines, resulting in a lack of working-class housing for the future city (Parnell 1993, 123). For the next few decades, the city’s population grew rapidly as an influx of Africans, Afrikaaners, and white immigrants from Europe came looking for work. The tensions that arose from this mixing, primarily tensions between Afrikaaners and English migrants, contributed to the outbreak of the Second Boer War (Parnell 1993, 20). As Ronald Mears explains, pass laws were originally introduced in 1896 to prevent desertion by restricting labor mobility, and labor was racially divided to save mine owners from having to pay the full subsistence cost of both white and black workers (Mears 2011, 4-5). Despite the differentiated provisions, urbanization and industrialization in Johannesburg during the early twentieth century resulted in increased racial integration of housing in the inner-city as labor needs required both poor Africans and poor whites. Due to the fact that mining activities were concentrated in the city-center, available urban land to construct working-class housing was scarce. During this time, the wage inequality meant that poor whites typically lived in boarding houses or rented rooms in private homes, while Africans were housed in workers’ compounds.

When mining activities decreased, leasehold rights to previously restricted prospecting sites were sold, allowing for cheap dwellings to be rapidly constructed for poor laborers that prioritized accessibility to their workplace (Parnell 2003, 618). While a limited amount of working-class housing did exist, the number of workers wanting to live in the city far exceeded the housing that was available. Moreover, many laborers actually preferred the more expensive slum-yards over the workers’ compounds. Segregationist laws like the Natives’ Land Act of 1913, which defined less than 10% of South Africa as black “reserves” and prohibited the sale or lease of land to blacks outside of the reserves, sought to restrict Africans from access to cities and effectively prevented Africans from land ownership throughout the country. However, the labor needs of Johannesburg’s growing manufacturing sector, especially in the wake of World War I, when increased industrialization also increased the need for African labor, meant that the Johannesburg municipal government ignored national policy and allowed racial mixing in these growing urban slums to occur (Parnell 2003, 619). A municipal system of exemption certificates obtained through employers did exist to grant African workers the right to live in urban areas. However, employers’ disregard for filling out the paperwork meant that most Africans resided in the city illegally.

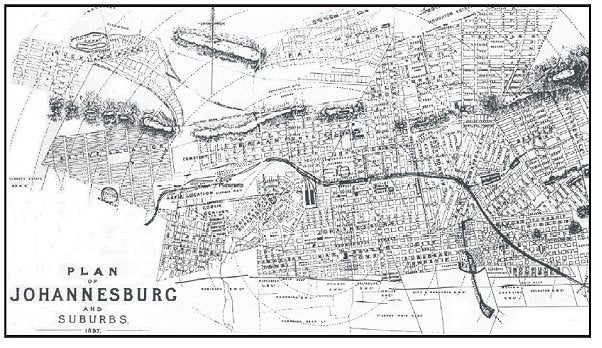

1897 map of Johannesburg.

Complaints about the inner-city slums had been going on for years, but when the population of urban poor came to have a higher percentage of whites in the 1930s, the city began a series of forced removals in order to acquire land for white-only housing to satisfy white demands for segregated housing. The destruction of slums, which was always racially motivated, as Parnell has argued, was originally justified for public health reasons, but eventually evolved into explicitly segregationist acts (Parnell, 1988, 311). Per the Native (Urban Areas) Act of 1923, cities were designated as white-only spaces, with Africans only permitted if they were employed by a white person, and “influx controls” were created to reduce access to cities by blacks. Empowered by this act, the city of Johannesburg undertook a number of slum clearances during the 1920s and 1930s. Under the act, Africans were theoretically assured alternative accommodations, while there was no such obligation for displaced whites. However, Parnell explains that the Johannesburg Council determined that there was a moral and practical obligation to ensure the success of the slum clearances by providing accommodations for the poor whites who had been displaced as well (Parnell 1988, 308). The vacant, accessible, and ecologically favorable area north of the city center became the site for subsidized housing development projects for the white workers. Africans, on the other hand, were sent to black townships typically to the south of the city center and farther away. However, the Johannesburg City Council encountered a roadblock as it pursued its goal of achieving a white-only urban center. The allocated township housing proved insufficient in accommodating all of the Africans being forced from the slums, resulting in the growth of illegal communities around the periphery of African townships (Parnell 1993, 185). To speed up the completion of the slum clearances, a development scheme focused on “sites and services” was adopted. The African slum dwellers were moved to townships outside of the city with the expectation that they would construct their own temporary housing until the government had money to build more permanent structures. The services offered were little more than water taps on vacant plots. Mears argues that the promise was ultimately not fulfilled to any significant extent, resulting in illegal squatting in shacks doubled up on land that was intended for lower-density residential occupation (Mears 2011, 11-12).

A woman and her child walk over rubble left behind after the Sophiatown removals, 1959.

During the apartheid era, these segregationist laws were more formally institutionalized and implemented at the national level by the Group Areas Act of 1950 and other laws, like the Pass Laws. Over the course of the second half of the twentieth century, Johannesburg saw different degrees of development unfold in different areas along racial lines, always reflecting the intent to reinforce racial segregation. Beall, Crankshaw, and Parnell show that infrastructure investment in the designated African areas practically stopped after about 1968 (Beall et al 2000, 114). While the apartheid era has been over for more than two decades, its legacy still remains evident in Johannesburg. An estimated third of the population in the formerly black-only township of Soweto live in small backyard structures, with about half of these being temporary shacks (Beall et al 2000, 111). The spatial distribution of the population in present-day Johannesburg largely follows the racial zoning imposed before and during apartheid. However, there is growing economic prosperity in the African neighborhoods with the emergence of middle-class homes in townships like Soweto that “are indistinguishable from the middle-class housing of the white suburbs” (Beall et al 2000, 117). Nevertheless, these neighborhoods coexist with the ever-present informal settlements within and around black townships.

Sources

Beall, Jo, Owen Crankshaw, & Susan Parnell. “Local Government, Poverty Reduction and Inequality in Johannesburg.” Environment and Urbanization 12, no. 1 (2000): 107–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624780001200108.

Mears, Ronald. “Historical development of informal township settlements in Johannesburg since 1886.” In Economic History society of southern Africa and ERsA workshop proceedings, Johannesburg, https://econrsa. org/system/files/workshops/presentations/2011/mears-paper-ersa-2011. pdf. 2011.

Parnell, Susan. Johannesburg Slums and Racial Segregation in South African Cities, 1910-1937. Place of publication not identified: publisher not identified, 1993.

Parnell, Susan. “Land Acquisition and the Changing Residential Face of Johannesburg, 1930-1955.” Area 20, no. 4 (1988): 307-14.

Parnell, Susan. “Race, Power and Urban Control: Johannesburg’s Inner City Slum-Yards, 1910-1923.” Journal of Southern African Studies 29, no. 3 (2003): 615-37.