By Rosalie Lovy

Questions

- Why are tourists drawn to Cairo? What do they see when they go and what are they directed to see by the industry?

- How has tourism changed since the end of the colonial era? Does modern tourism overcome the exoticism of earlier times?

Discussion

Modern tourism in Cairo has developed to reflect the variety of tourists who are drawn to Egypt and to Cairo specifically. Elements of the industry rely on ancient sites, perceived elements of traditional culture, or a sense of exoticism and escape sought particularly by Western tourists. Each of these elements has prompted significant investment and development of tourist infrastructure, resulting in an industry now integral to the Egyptian economy. This vibrancy, however, does come at a cost to government investment in ordinary Egyptians and Cairenes as well as to the environment.

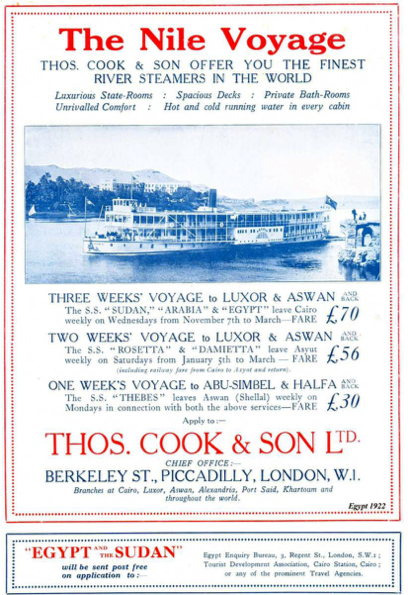

At the beginning of modern tourism during Europe’s industrial revolution, Western tourism to Egypt was often prompted by an attraction to the exoticism of the Arab World. However, the nature of the first mass-marketed popular tourist programs, created by the Thomas Cook travel company, was quite sheltered. F. Robert Hunter, an expert on colonial history of the Middle East and known from his work on Palestinian politics, describes the growth of this company and its effect on the tourism industry in Egypt. This was within the context of colonial control of Egypt, which created and maintained a stark separation between native Egyptians and European visitors and officials. These early tours capitalized on romanticized representations of Cairo and of Egypt while remaining within this segregated and artificial framework. Cairo was the center of this enterprise, providing a home base for communications resources and connections to the colonial presence in Egypt at the time. (Hunter, 2004) At the same time, the development of luxury resorts and cruises in the 19th and early 20th century provided employment, drawing labor from the agricultural sector into service jobs. The cruise industry continues to thrive, particularly on the segment of the Nile between Cairo and Luxor.

The luxury tourist experience remains popular today. Luxury hotels within Cairo as well as resorts on the outskirts offer a high-end travel experience which can be experienced completely divorced from contemporary Egyptian culture. These institutions remain large local employers and support the government through resort taxes. Outside the city, spas and ecotourist “glamping” sites (“glamourous camping”: basically hotels with a rustic veneer) provide a more rustic experience, again totally detached from contemporary Egyptian culture. These experiences are inexpensive by European standards though they are exorbitant for native Egyptians. Such resorts came into being in the 19th century when European tour companies brought an influx of upper middle-class tourists who sought a sheltered travel experience and were willing to pay for better amenities. This group is distinct form the elite colonial class or very wealthy tourists, whose hotels and apartments were beyond the reach of the target market for the new wave of boat cruises and tours (Hunter, 2004).

The feeling of remote otherness sought by European tourists also promoted illicit activities which created new revenue streams for the drug and prostitution industries. This continues today. Behbehanian posits that this phenomenon is linked to Islamic culture, which traditionally has had high levels of recreational drug use due to the banning of alcohol for religious reasons. This means that drugs such as opium, heroin, and hashish were relatively easy for wealthy tourists to procure. This reputation made Cairo and Egypt in general popular among upper-class European tourists, who set up their own cafes with alcohol to circumvent local abstinence while also enjoying the more relaxed attitude towards drug use that in Europe at the time. Opium and hashish establishments during the colonial period became important social institutions, similar to prestigious hotel bars or social clubs (Behbehanian, 2000), and contributed to the growth of villages and towns adjacent to tourist sites.

The ruins of ancient Egypt have drawn visitors for centuries. Travelers and merchants from within the Arab World as well as from across the Mediterranean and from below the Sahara sought to bring home artifacts from the Pharaohs after a visit to Cairo or its previous incarnations. This has resulted in grave robbing and forgery to supply the demand for artifacts. In contemporary history, this fascination with the ancient has led to significant investment in the preservation of ancient sites such as the Pyramids at Giza and the temples of the Nile Basin. The international effort to preserve ancient ruins at the time of the construction of the Aswan Dam exemplifies the importance of these monuments. Lucia Allais, an architectural historian, shows that the heritage status bestowed upon the monuments by the UN allowed the mobilization of a large community of international scientists and financial backers. In analyzing the monuments chosen for restoration as well as their ultimate locations after the project, Allais claims that tourist convenience was a major deciding factor in the project. The choice to reconstruct the monuments in closer groupings so as to facilitate tours, as well as the gifts to foreign countries of treasures such as the Temple of Dendur, show the perceived importance of these sites in promoting tourism. Foreign participation in the project should thus be seen as motivated not only by the interest of preserving historic sites but also by the desire for new items for museum collections. (Allais, 2012) Many tourists continue to visit Egypt specifically for these ancient sites rather than for the contemporary cultural experience. These assets form a core piece of the government’s strategy to promote tourism.

The UN’s involvement in the relocation of threatened temples is not the only example of international involvement for the sake of Egypt’s tourist industry. Mitchell details the World Banks’s efforts to promote tourism in Luxor in order to create economic opportunities for locals. These projects included land appropriation for tour bus parking, training in production of souvenirs, and subsidies for the operation of hotel schools teaching hospitality related career skills. These programs did help build the tourism industry, but they also disrupted local economic activity and took many young people out of their communities and away from family enterprises.

City planning of Cairo has similarly emphasized tourist convenience as the industry has grown. The preservation of historical architecture as well as the implementation of English-language signage indicates the prioritization of tourism in Cairo itself. Ahmed Sedky outlines the trends in architecture and claims that the aesthetic preferences were at first based on the ruler’s tastes but eventually turned outwards to attract outside visitors (Sedky, 2009). In Mitchell’s view, these activities in the 1980s and 1990s helped foment discontent among the young generation, which contributed to the context of the Arab Spring. (Mitchell, 2013)

Some contemporary tourists are looking for a more “authentic” experience of Egyptian culture. These tourists support the large guided tour industry which provides curated experiences of daily life in Cairo. Walking tours and bus tours are popular as they help navigate the large and confusing urban area as well as bridge the language gap and provide security. Tourists are also drawn to specific sites within the city including historic mosques, bazaars, and squares. However, tourists seeking untouched Egyptian cultural sites often find carefully preserved and curated reflections of the tourist’s view of Cairo. An example of this is the Khan al-Khalili market in Cairo. This market has been in operation for centuries and over time has expanded significantly to now encompass several city blocks. In the early days of European tourism, the market was known as a hot spot for serious collectors of Egyptian artifacts and architectural features. As the flow of Westerners grew, the availability of these items decreased as more and more of the city and surrounding ruins were plundered. In addition, the locals found they could easily do good business with imitation products and souvenir-quality materials. Now, the bazaar is almost exclusively maintained for tourists and supports a large number of local vendors and craftsman who make clothing, décor objects, cookware, and other objects for the tourist market. Thus, while Khan al-Khalili is marketed as a taste of the real Cairo, it is in fact carefully targeted towards foreigners. (Alsayyed, 2011) In reality, markets and bazaars do still hold an important place in Cairo, but western-style supermarkets and convenience stores also exist in increasing numbers.

Tourism provides essential revenue for the national government as well as individuals working in the industry. For this reason, the state has justified disproportionate expenditures on supporting it in the form of hotel construction, preservation efforts, and beautification of downtown Cairo (Sedky, 2009). There is some criticism of this prioritization of the tourist industry. One of the strongest critiques can be examined in the response to Cairo’s recently announced Cairo 2050 visionary plan for the city’s development. The plan aims to relocate the densely populated informal settlements on the outskirts of downtown to newly developed satellite towns, which would alleviate some of the problems in these areas suffering from extreme poverty and lack of municipal services. The plan focuses, however, not on this significant portion of the population but rather on the downtown areas. The plan outlines a complete overhaul of much of downtown Cairo, particularly along the Nile, in order to create a modern business district attractive to foreign companies as well large swathes of pristine parkland and attractions for tourists. The project is in many ways more focused on attracting further international involvement and tourism rather than on improving the city for the sake of its residents (Tarbush, 2012).

Overall, Cairo has been and will continue to be shaped by the desires of its tourists. The government continues to prioritize this significant source of revenue. The relationship between native Cairenes and tourists remains complex and will be tested as the country continues to modernize away from the traditional cultural elements that attract visitors.

Sources

Allais, Lucia. “The Design of the Nubian Desert: Monuments, Mobility, and the Space of Global Culture.” In Governing by Design: Architecture, Economy, and Politics in the Twentieth Century, by Aggregate, 179-215. Pittsburgh, Pa.: University Of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

Alsayyad, Nezar. “Modernizing the New, Medievalizing the Old: The City of the Khedive.” In Cairo, 199-228. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Behbehanian, Laleh. “Policing the Illicit Peripheries of Egypt’s Tourism Industry.” Middle East Report, No. 216 (2000): 32-34.

Hunter, F. Robert. “Tourism and Empire: The Thomas Cook & Son Enterprise on the Nile, 1868-1914.” Middle Eastern Studies 40, No. 5 (2004): 28-54.

Mitchell, Timothy. “Worlds Apart: An Egyptian Village and the International Tourism Industry.” In the Arab Revolts: Dispatches on Militant Democracy in the Middle East, edited by Mcmurray David and Ufheil-Somers Amanda, 76-82. Indiana University Press, 2013.

Sedky, Ahmed, “The Current Meaning of Historic Areas in Cairo.” Living with Heritage in Cairo: Area Conservation in the Arab–Islamic City, American University in Cairo Press, 2009, pp. 3–36.

Tarbush, Nada. “Cairo 2050: Urban Dream or Modernist Delusion?” Journal of International Affairs, vol. 65, no. 2, 2012, pp. 171–186.