Questions:

How is Singapore’s history gathered through oral histories? Who archives and creates these oral histories? What do they tell us about the relationship between the archivist group and the citizens? What are some critiques of Singapore’s oral history archive?

Discussion:

It’s no secret that the PAP cares deeply about the country’s “story.” For example, Singaporean schools teach a history curriculum dubbed “the Singapore Story” that closely follows the narratives pushed in President Lee Kuan Yew’s own memoirs of the government’s success (Blackburn 26). Thus, an analysis of Singapore’s oral history presents a fascinating dichotomy between the government’s tight grasp on the nation’s narratives and the influence of families passing down their own culture and values to the next generations.

For much of this analysis, I will look to Nanyang Technological University’s Professor Kevin Blackburn’s analyses of Singapore’s Oral History Archives. An expert in Malaysian and Singaporean history, especially during World War II, Blackburn has written chapters in two different books covering oral histories in Asia. One chapter is called “Family Memories as Alternative Narratives to the State’s Construction of Singapore’s National History,” and the other is called “Family Memories as Alternative Narratives to the State’s Construction of Singapore’s National History.”

The largest archive has been curated by Singapore’s Oral History Centre, founded by the Ministry of Culture in 1978 (Blackburn 2008, 32). For the first few years of operations, the Oral History Unit focused primarily “on interviewing former government members and senior civil servants,” which created an unbalanced archive that was weighted to the government perspective (Blackburn 32, 2008). After a few years, in 1985, the commission opened its interviews up to a more diverse group of interviewees. Lim How Seng, who coordinated the oral history projects, admitted that the interviewers were given instructions not to ask “challenging questions” or discuss specific topics that “were clearly off limits, such as eliciting criticism of Lee’s decisions” (Blackburn 34, 2008). This bias affected not only the questions asked in the oral histories, but also the selection of interviewees. For one oral histories initiative, named “the Pioneers” project, Lim admitted in an interview that the project aimed to interview “wealthy and powerful businessmen,” who used the interviews as self-serving opportunity to create their own “rags to riches” stories, which went unchallenged by the interviewers (Blackburn 35, 2008).

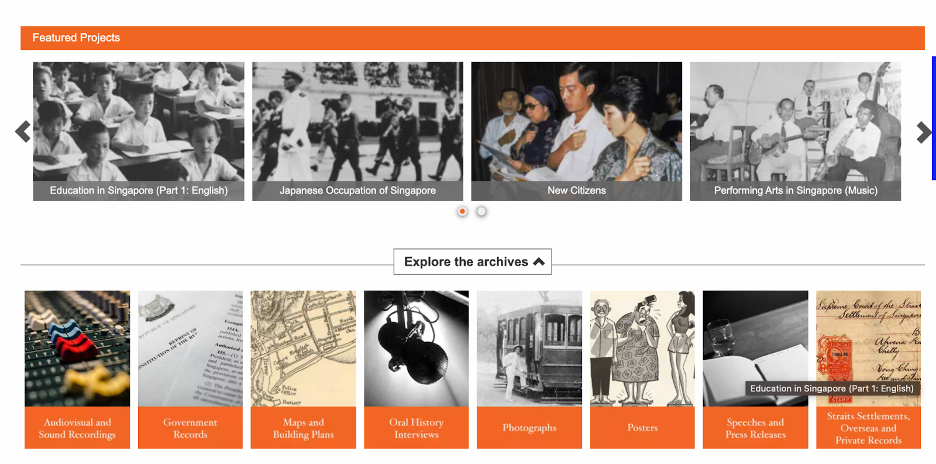

As shown in figure 4, the archive itself is divided into sections called “projects” that each cover a specific part of Singapore’s history. For example, there is a “Japanese Occupation” project, a “Sports Personalities” project, a “Print Media” one, and even one covering the “Political History of Singapore 1945 to 1965” (National Archives of Singapore 2021). Within each project, there are hundreds of names of interviewees that cover stories on the project’s topic (National Archives of Singapore 2021). Each interviewee has their own page and access number on the archive, and on their page one can either listen to the interview itself, watch it if video is available, or even review a pdf document with a full transcript of the interview (National Archives of Singapore 2021). According to Blackburn, the interviews are conducted by members of Singapore’s Oral History Unit (Blackburn 32, 2008).

Blackburn also notes that given the context of the Oral History Centre’s “nation-building mission,” academics and historians “are reluctant to use” material from the archives (Blackburn 38, 2008). Blackburn’s qualms with the Oral History Centre’s archives derive primarily from the selections of oral histories that are chosen to promote the “government-endorsed nation-building message (Blackburn 43 2008). In his “History from Above: The Use of Oral History in Shaping Collective Memory” chapter, Blackburn concludes that “the use of oral history by the state-run Oral History Centre” exemplifies “how national repositories of oral history in developing countries are strongly influenced by the nation-building agenda mandated by the state” (Blackburn 44, 2008). Blackburn’s evidence, however, does not show that the archive itself was censored, but instead that the nation’s textbooks choose quotations from the archive that are misleading. Blackburn names two widely used school textbooks, Beyond the Empires: Memories Retold and Understanding our Past: Singapore from Colony to Nation, which both promote a nationalist narrative of “survival” of the Japanese Occupation to come out as a united Singaporean people (Blackburn 43, 2008). For example, Understanding our Past “de-emphasize[s] the ethnic tensions that characterized the Japanese Occupation and highlight the forging of a nation out of the common suffering of all,” when in reality, the Japanese treated the Malay and Singaporeans well and mostly persecuted the Chinese (Blackburn 43, 2008). While Blackburn is right in criticizing the history textbook for misrepresenting the “differential treatment between the Chinese and Malays,” it is probably unfair to blame the Oral History Centre itself, since there are interviews that shed light on this differential treatment. One such example comes from a randomly selected interview from the Japanese Occupation section with a woman named Ms. Esme Woodford, who was born in 1926 in East Malaysia and immigrated to Singapore in 1936 Woodford 2. In the interview, she reveals that the “well disciplined” Japanese soldiers did not “commit atrocities… in Singapore” on most people (Woodford 14). According to her, she had heard that “there was a lot of atrocities in Malaysia,” but the killing of civilians was mostly confided to rural and isolated areas (Woodford 13).

Upon reviewing Singapore’s oral history archives, the themes discussed above become immediately clear. After searching the word “housing” in the database, 90% of the first twenty interviewees worked for the Housing Development Board in some capacity (National Archives of Singapore 2021). Their interviews, like that of Alan Fook Cheong, who served in the Urban Redevelopment Department of the HDB, focus largely on not only the successes of the HDB, but also how they fit into the Singapore Story. In discussing the HDB’s involvement in resettling the displaced Singaporeans after the Bukit Ho Swee fire, the conversation does not touch on the challenges of the HDB’s controversial land acquisition. Instead, the interview frames the HDB’s actions even less as achievements, and more as “contributions” the government made on behalf of the Singaporean “squatters” (Cheong 1997). The subjects that Cheong refrains from discussing are discussed at length in Loh Kah Seng’s book Squatters into Citizens, which reveals a “more nuanced and complex story” than the HDB’s narrative of an “unpleasant and dangerous… squatter community” (Loh 2013). “In reality,” Loh writes, “the squatters were progressive and urbanized, and had [an] effective social autonomy” (Loh 2013). Indeed, there are certainly two sides to the story of the HDB’s acquisition of land in the kampong squatter communities.

While the archives are certainly self-censored, it would be fallacious to say that the more than 37,000 interviews were conducted without mention of any government failure. Though the topic of HDB’s problematic land acquisition laws rarely show up in interviews, I did actually find a handful of interviewees willing to discuss not just that topic, but also the subject of government corruption. Singapore’s government is known for its hard stance on corruption, which Tan Chok Kian, an officer in the Ministry of National Development (part of the HDB), verified in his testimony. He explained that working for such a powerful government branch presented an environment that was particularly “open to tremendous temptations” (Tan 33). In fact, Mr. Tan remembers that “three Ministers lost their jobs because of alleged corruption” (Tan 33). Despite those cases, he credits the “strict control” and “severe penalt[ies]” given to “wrongdoers” that kept the number of corruption cases to only three (Tan 35). Mr. Tan also freely discussed the “massive acquisition… of land at very very low prices,” and he even mentions how the predatory “Fire Clause in the Acquisition Act” allowed the government to acquire land at one-third the market price (Tan 37). Mr. Tan did not go into detail about how the HDB used the fire clause aggressively by lumping sets of ten houses under one unit, meaning if just one of them was burnt then the HDB could invoke the clause (Chua 2011). He also did not mention the clause about the HDB’s authority to pay very low prices for any land that had what the government deemed “squatter” houses, but nonetheless it is significant he talked about the Fire Act and its importance in his interview (Straits Times 1961). It is worth noting that Mr. Tan viewed the unfair land acquisitions as a necessary evil with good intentions. As he says, the government could only sell public housing “at a very, very low price,” to enable mass homeownership if it “really took advantage” of the landowners by buying land for many times below market price (Tan 37).

While these oral histories mostly fall under the PAP’s propagated national narrative, they still provide crucial data and fill gaps in the country’s history that would otherwise remain unknown today. A UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) fact sheet on the International Memory of the World Register of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore credits the Singaporean Oral History Centre Archive’s Japanese Occupation section as a highly important archive for many reasons. It is uniquely comprehensive, gives partially undocumented insight into Japanese military strategy at the time, and reveals a diverse set of race and class relations in accounts on British, Australian, New Zealander, Malay, Japanese, and Chinese interactions (UNESCO 2). Most significantly, the Japanese practice of destroying all records “in the days leading up to their surrender” in 1945 left a major void in the history of the 42 month-long occupation (UNESCO 1). Indeed, UNESCO even goes as far as to say that Singapore’s oral history archive provides “significance beyond national history” (UNESCO 5).

While the archive certainly highlights the same themes presented in the “Singapore Story” that are written by the hand of Lee Kuan Yew himself, the accounts are nonetheless authentic in their own right. The archive’s stories are not less genuine nor less important just because both interviews fit a narrative of PAP-born national pride. The stories are compelling, original, and personal; thus, the archive provides significance both in a historical sense, as the UNESCO fact sheet praises, and in the world of oral histories itself.