By Kelly Liu

Questions

How has war affected the history of Nanjing? How have memories of war been interpreted locally, nationally, and internationally?

Discussion

The sources reviewed here show how, over the course of centuries, Nanjing has been repeatedly ravaged by rebellion and dynastic upheaval, with each successive regime attempting to shape the city according to their visions of political order. This report will explore how the millenarian Taiping movement and the modernizing Republic both saw in Nanjing’s wartime destruction a blank slate on which to construct a new state. The bulk of this report will focus on the Nanjing Massacre, particularly the transfiguration of the massacre as a localized event into a symbol of national victimhood. This transformation sheds light on the ways in which local memories and practices are subsumed in the nation’s narratives.

Nanjing’s Ming city walls still stand today, the product of repeated cycles of destruction and restoration. When the city was elevated to the status of imperial capital in 1368, its Ming rulers embarked on a frenzy of wall-building to defend the region from pirate attacks. Nanjing’s walls consumed the labour of over 200,000 workers over the course of twenty years. City walls were seen as inland defence frontlines, safeguarding not only the walled city itself, but also the surrounding regions by disrupting supply chains to pirates (Fei 2009, 80). Nanjing’s walls preserved the city from pirates and stayed intact through conquest by the Qing (1644-1911), whose forces took Nanjing peacefully following the flight of the last Ming emperor. However, the city walls would fall under the guns of Taiping rebels some two hundred years later (Wooldridge 2015, 95).

In City of Virtues, historian Charles Wooldridge draws on the diary of scholar Wang Shiduo to examine new spatial and temporal practices in the Taiping “Heavenly Capital.” After seizing Nanjing from its Qing administrators on March 19, 1853, Taiping leader Hong Xiuquan, who believed himself to be the younger brother of Jesus Christ, set about reorganizing the city as a microcosm of heaven. According to Taiping cosmology, the world was filled with demons that could only be dispelled with God’s truth. These demons were understood as the Qing Manchus and traditional religious and ritual practices. Thus, the Taiping slaughtered banner families, razed Qing garrisons, and tore down temples (Wooldridge 2015, 95). In this newly emptied space, they enacted their vision of cosmological and political order. The Taiping rulers abolished private property and divided families into single-sex social units called guan (dwellings). Each guan contained twenty-five members of the same occupational group, who lived and ate communally.This reorganization of space and time ruptured existing practices and understandings of everyday life, driving many residents to flee the city as refugees (Wooldridge 2015, 99-100). For instance, Wang Shiduo endured separation of his family into different guan until his daughter died, unattended by her family. He escaped to neighbouring Anhui province in December 1953 (Wooldridge 2015, 106). Wooldridge provides a fascinating account of Taiping spatial practices but his discussion of residents’ lived experiences is limited by his focus on the perspective of Wang Shiduo, an elite literati diarist.

In 1864, Qing-allied forces retook the city, reducing most of it to rubble. However, as historian Charles Musgrove shows in “Building a Dream,” for nationalists like Sun Yat-sen, Nanjing’s destruction offered a blank slate for constructing a “model capital” for the new Republic. The National Capital Planning Office was established in 1928 to build the city according to international standards for hygiene, communications, and transportation. The office was led by Harvard-trained engineer Lin Yimin and staffed by planners influenced by the City Beautiful Movement, which advocated the use of “scientific” city planning to maximize efficiency as well as the creation of parks and public spaces to foster social harmony. Nanjing’s planners adopted rationalizing measures that would maximize the city’s economic growth, including a grid plan for roads and zoning restrictions that separated the city into functional zones for living, working, and recreation (Musgrove 1999, 148). However, above all, planners were concerned with reshaping Nanjing’s urban space to express a new political order based on formally equal, self-regulated citizens with a sense of responsibility to the nation (147). Leaders lauded plans for being “systematic” and expressing “freedom and equality in the Chinese republic” (Musgrove 1999, 146). Musgrove shows how city planning in Republican China encapsulated conceptions of modernity, nationalism, and political order.

However, most of the Nationalist government’s plans for Nanjing went unrealized due to capital shortages. What little they did accomplish was destroyed in the Japanese invasion of the city on December 13, 1937 and the six weeks of murder, rape, robbery, and arson that followed, a period now known as the Nanjing Massacre. In Forgotten Ally, historian Rana Mitter highlights the “ghastly price” of Chinese resistance, paid in human life, ecological disaster, and the destruction of infrastructure. According to the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE) held in Tokyo after the war, “‘approximately 20,000 cases of rape occurred within the city during the first month of the occupation.’” In addition, the IMTFE claimed that occupying forces killed 30,000 Chinese combatants and 20,000 male civilians. (Mitter 2014, 139). The occupation also destroyed eighty percent of Nanjing’s infrastructure, mostly through fires set by retreating Chinese troops and by Japanese soldiers terrorizing the civilian population (Mitter 2014, 5-6).

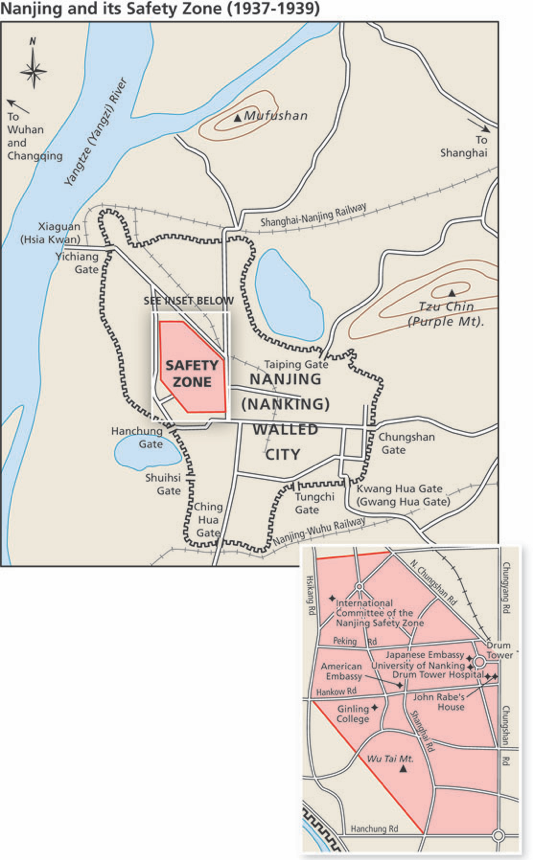

The primary documents of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone give us a glimpse into how occupation reshaped urban geography and spatial conceptions. As government leaders fled in October 1937, a small group of foreign businessman, missionaries, and doctors established an International Safety Zone within the old walled city, which included the campuses of Nanjing University and Ginling Women’s College (Mitter 2014, 125-127; see Fig.1). After the city fell, approximately 80,000 of the 200,000 residents left in Nanjing crowded into refugee camps set up by the International Safety Zone Committee, which noted in a petition to the Japanese Embassy on December 21, 1937 that looting and burning have “reduced the whole civilian population to one vast refugee camp” (Brook 1999, 49). From within the Safety Zone, members documented “cases of disorder by Japanese soldiers” and pled for Embassy officials to restore order. The conditions inside the zone were dire: Japanese soldiers continuously entered to rape refugees, sanitation was utterly inadequate, the hospitals were overrun with victims, and food and fuel was running out in the absence of commerce (Brook 1999, 2-10). A public health crisis was brewing as sewage overflowed and corpses piled up in rivers and ponds (Brook 1999, 76). The rapes and murders began to abate in late January 1938, and a new city government under Japanese command took over the administration of the Safety Zone and slowly began to restore a semblance of order (Mitter 2014, 140). The documents in Brook’s compilation are invaluable for providing some of the only first-hand accounts of the Massacre (due to the Japanese media blackout) but they are limited in scope for they only record what was happening in the Safety Zone itself, and not in the city as a whole.

Figure 1: Map of the International Safety Zone indicating its location within the city. Source: “Nanjing and Its Safety Zone (1937-1939),” Facing History and Ourselves, accessed May 7, 2020.

For decades, the massacre in Nanjing persisted in local memory rather than national consciousness. During the war, the Nationalist government was aware of the incident but found chemical warfare and the carpet bombing of Chongqing more politically useful in gaining international support (Yoshida 2006, 27). The massacre was not understood as a unique and isolated incident of Japanese violence. After 1945, the war between the Nationalists and the Communists resumed and both sides focused on winning the civil war, rather than remembering the Japanese invasion. When the Communists emerged victorious in 1949, they preferred to focus on reconstruction and national strengthening, and not China’s victimhood (Yoshida 2006, 62). However, in Nanjing, local residents continued to preserve the memory of the massacre. From 1960 to 1962, the Department of History at Nanjing University conducted interviews with survivors, which were collected in an eight-chapter manuscript. The manuscript was classified by the central government (Yoshida 2006, 69-70).

Thus, historian Takashi Yoshida argues that the understanding of the Nanjing Massacre as a symbol of Japanese aggression and China’s victimization by imperialist powers is a recent construct. The massacre entered national and international consciousness due to geopolitical shifts in the 1970s and 1980s. The internationalization of the Nanjing Massacre began in Japan, when the country’s economic rise emboldened conservative revisionists to publicly deny Japanese wartime atrocities. Ironically, the controversy over Japanese history textbooks in 1982 drew regional and international attention to Japan’s wartime actions. This period coincided with China’s economic liberalization and the Party’s concerns about the dangers of “spiritual pollution” from the West and the corresponding need to inculcate patriotism and nationalism among youth. Thus, from 1982, testimonies and witness accounts of Japanese atrocities began to appear in the Chinese press and the Nanjing Massacre became an important part of the Patriotic Education Campaign in schools (Yoshida 2006, 102). The Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, built on the site of a mass grave, opened on August 15, 1985 to mark the fortieth anniversary of Emperor Hirohito’s announcement of Japan’s surrender (Yoshida 2006, 107). Yoshida’s careful study of Chinese, Japanese, and American historiography of the massacre shows how historical memory is deployed for political purposes. Local memories have been subsumed into nationalist discourses as Nanjing has become inextricably linked to the patriotic narrative of China’s Hundred Years of Humiliation at the hands of foreign imperialists.

The sources reviewed illustrate the ways in which new regimes seized on wartime destruction to enact their political visions. The Taiping Kingdom and the Republican government sought to physically inscribe radical new orders onto the urban space of Nanjing, while the Communist Party has discursively constructed the Nanjing Massacre into a rallying point for nationalism. In each case, we see how local practices and lived experiences are subsumed under grand, national narratives.

Sources

Brook, Timothy, ed. 1999. Documents on the Rape of Nanking. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Fei, Si-yen. 2009. Negotiating Urban Space: Urbanization and Late Ming Nanjing (Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2009).

Mitter, Rana. 2014. Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937-1945. Boston: Mariner Books.

Musgrove, Charles D. 1999. “Building a Dream: Constructing a National Capital in Nanjing, 1927–1937.” In Remaking the Chinese City, edited by Joseph W. Esherick, 139–58. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Wooldridge, Chuck. 2015. City of Virtues: Nanjing in an Age of Utopian Visions. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Yoshida, Takashi. 2006. The Making of the “Rape of Nanking:” History and Memory in Japan, China, and the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.