By Luan Tian

Questions

- What were the structural and historical causes that initially encouraged the growth of tourism in Melbourne and how have they continued shaping the city’s development?

- What are the various cultural and urban identities that the city of Melbourne takes on to attract tourists and how have they changed over time?

- In what ways has tourism altered the physical urban space and the lived experience of its residents?

- Who were the main agents in the city’s rebranding?

Discussion

In its mid-twentieth century transition from an industrial city to a tourist city, Melbourne relied on a strategy integrating infrastructure development with urban rebranding. This discussion identifies the historical conditions and primary actors in producing urban change. It also explores how spatial redevelopments enabled the city’s attempts to rebrand itself while its evolving identity manifested in urban space through the city’s physical transformations.

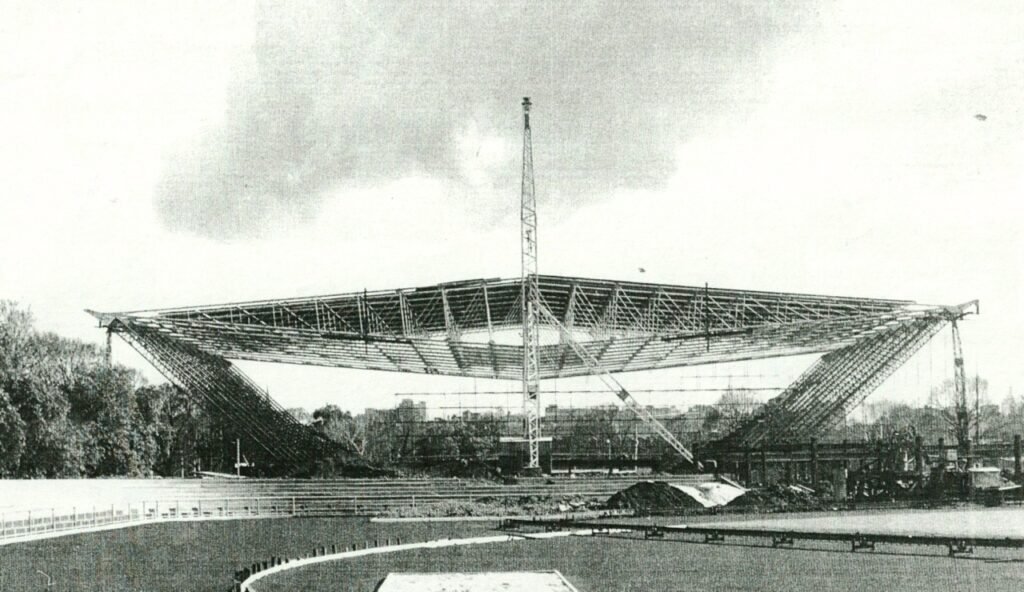

Figure 1: Olympic Pool Building for the 1956 Melbourne Games. (Engineers Australia)

Figure 2: “Olympic Games Melbourne” 1956 Poster by Richard Beck. (Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences)

The 1956 Summer Olympic Games provided a platform for attracting international visitors and an impetus for urban change. Initially, prominent social and cultural critics in Melbourne responded harshly to the decision to host the Games. Robin Boyd, a locally-based architect, characterised the city as a “sleepy city” and a “colonial remnant” unfit for global attention (Hughson 2012, 273). At the same time, however, Boyd participated in a range of projects aimed at altering public perceptions of Melbourne and rebranding the city. The largest project was the design and construction of the Olympic Pool Building. Boyd served on the judging panel and deemed the project to be a modernist achievement and the “first fairy story of Australian building” (Hughson 2012, 273). Furthermore, the Olympic poster designed by Richard Beck embodied the city government’s rebranding exercise to “enhance Melbourne’s reputation as a cosmopolitan city for international business” (Hughson 2012, 278). Hughson’s article historicises Beck’s poster to explain its resonance with the city’s agenda to modernise. The poster departed from nationalist iconography and discarded the common semi-naked male body motif to figure, instead, an abstract invitation card, in the “clean-lined, singular, geometrical” form of the International Style, as an invitation to international visitors and investment (Hughson 2012, 270). Finally, the interconnection between urban space and branding was clearly visible in street decorations such as Boyd’s ceramic sculptures and Beck’s spinmobiles. These street decorations were installed and “brought an element of fun” (Hughson 2012, 276), in contrast, for example, to the city’s traditional liquor licensing laws prohibiting bars from opening past 6pm (Hughson 2012, 273). In these instances, urban rebranding did not rely on legislative change but rather on a remaking of Melbourne’s urban spaces.

In addition, the redevelopment of existing buildings in Melbourne for purposes of tourism provided an opportunity to reinforce its local identity. The architecture of the Old Melbourne Gaol displays strong imperialist influences, as a replication of Pentonville in London, and its function evokes Australia’s heritage as a British penal colony (Welch 2012, 585). Even though British imperialism has shaped Australian urban spaces in very significant ways, Welch’s article complicates the claim that penal institutions solely reference the colonial past, arguing instead that as the Old Melbourne Gaol was converted into a museum, it allowed for the production of “cultural meanings” rooted in local history (Welch 2012, 585). His case study of the Gaol emphasises the exhibit on Ned Kelly, a criminal outlaw hanged there in 1880. Ned Kelly has been mythologised as a rebel against oppressive law-enforcement and society’s unequal distribution of land and wealth by fighting the police authorities (Welch 2012, 605). For Welch, the combination of Ned Kelly’s specific execution site and the museum exhibit’s glorification of his symbolic legacy suggests that this instance of penal tourism is attempting to convey a uniquely Victoria-local identity in contrast to the Australian identity at-large (Welch 2012, 610). Whereas the new constructions for the Olympic Games looked to the future, the Old Melbourne Gaol museum’s retelling of Ned Kelly’s story draws upon local history to convey the city’s individual identity.

Figure 3: Interior of the Old Melbourne Gaol. (National Trust Victoria)

The waves of urban redevelopment and rebranding from the 1970s to the 1990s followed a similar pattern. The historical cause was commonly an economic crisis and the solution was to improve Melbourne’s attractiveness as a tourist city. In 1977, two reports published on the condition of the inner city highlighted the loss of blue-collar and unskilled jobs, and warned of unemployment, social disorder, and urban decay (O’Hanlon 2009, 30). At the time, Melbourne lost its competitive edge against other Australian cities, in particular Sydney, which had restructured economically to strengthen the media and finance industries, and Brisbane, which attracted tourism and mining with its sunny weather and rich natural resources (O’Hanlon 2009, 32). In response to economic crisis caused by the decline of manufacturing, Melbourne decided to specialise as an “events city” to expand the city’s tourism industry (O’Hanlon 2009, 31). Hanlon’s article explores the physical transformations in association with the city’s competitive strategy and how Melbourne avoided the social unrest that was predicted in the 1970s. The article emphasises the role of the state government under Labor leader John Cain and the state Treasurer Rob Jolly. The state government tailored an infrastructure program characterised by Keynesian policies in the 1980s, spending public funds to redevelop existing stadiums and build new facilities to establish Melbourne as the home of major sporting events (O’Hanlon 2009, 33). Furthermore, with the closure of factories along South Bank, the state government intervened to convert the area into the Arts Centre; the facility was completed in the early 1980s to host cultural events (O’Hanlon 2009, 34). These major infrastructure development projects were enabled by a transfer of planning power from the municipal level to the state level (Blomkamp and Lewis 2019, 115). In addition to providing public funding, the state government was able to reduce application processing times fivefold, thereby increasing efficiency and making private sector participation and investments more attractive (Blomkamp and Lewis 2019, 121).

The pattern repeated itself in the 1990s with the procurement of a casino and leisure complex in South Bank. Hall and Hamon traces three waves of casino development in Australia, beginning with smaller cities developing European-style casinos in the 1970s to large, high-turnover, American-style casinos in medium-sized cities in the 1980s (Hall and Hamon 1996, 31). The third wave constituted of casinos built in Melbourne and Sydney in the 1990s (Hall and Hamon 1996, 31). The Melbourne casino was envisioned as a major public works project and a source of tax revenue, necessitated by large amounts of public debt, growing unemployment, and “the collapse of several major financial institutions” (Hall and Hamon 1996, 32). To address severe economic concerns, Melbourne promoted “gaming tourism” (Hall and Hamon 1996, 35). This example continues the trends of previous attempts to rebrand Melbourne. First, it is clear that regardless of how urban identity is conceived to attract tourists, whether as a “modern city” in 1956, an “events city” in the 1970s and 1980s, or a “gaming city” in the 1990s, large-scale infrastructure development was the primary mechanism to achieve its branding goals. This did not mean, however, that infrastructure always took precedence over, or determined, urban branding. Hall and Hamon articulate how Melbourne’s branding also expressed itself through urban planning and determined the built environment. For example, the casino and leisure complex followed a competitive bidding process, in which the key selection criterion was design; private sector consortiums argued that their entries were “more Melbourne, more cultural and more understated” in response to state government solicitation (Hall and Hamon 1996, 33).

Second, the state government played the predominant role in urban planning. Blomkamp and Lewis suggest that the transfer of planning power was a central governance change that permitted the development and redevelopment of Melbourne’s sports facilities, arts complexes, and the casino (Blomkamp and Lewis 2019, 116). For example, in the procurement of the casino, the City of Melbourne Council was largely “excluded…from the planning and selection process” (Hall and Hamon 1996, 33). However, the central argument of Blomkamp and Lewis’ research is that the municipal government was not completely passive; the public policy success in Melbourne’s rebranding for tourism depended on the complementary nature of state and municipal activities. They label the state’s large-scale infrastructure projects as “‘hard’ instruments” in contrast to the “soft” approach of the municipal government aimed at improving liveability (Blomkamp and Lewis 2019, 118). The division of labour between the two levels of government permitted the municipality to “do things differently” and improve the lived experiences of its residents (Blomkamp and Lewis 2019, 133). One aspect of the latter was a campaign to bring arts and cultural events to Melbourne, thereby making use of the state’s investments in infrastructure and facilities; Blomkamp and Lewis claim that the label of a “creative city” was formulated in Melbourne before anywhere else in the world (Blomkamp and Lewis 2019, 123-4). Another element was spatially-defined, as seen in the pedestrianisation of the city and increasing the availability of public gathering spaces such as cafés (Blomkamp and Lewis 2019, 126-7). Thus, liveability took physical shape in Melbourne’s urban spaces. The emerging identity as a “liveable city” was then leveraged to advertise Melbourne to tourists, international students, and investors (Blomkamp and Lewis 2019, 124).

As historical conditions in Melbourne necessitated an increasing emphasis on tourism and tourist revenue, the state and city governments were challenged to incorporate its branding and cultural identities into urban planning, infrastructure development, and the built environment. Melbourne’s physical appearance at any time, therefore, embodies the accumulation of its tourism strategies and urban rebranding.

Sources

Blomkamp, Emma, and Jenny M. Lewis. “‘Marvellous Melbourne’: Making the World’s Most Liveable City.” In Successful Public Policy: Lessons from Australia and New Zealand, edited by Joannah Luetjens, Michael Mintrom, and Paul ’t Hart, 113-137. Canberra, Australia: ANU Press, 2019.

Hall, Michael C. and Christopher Hamon. “Casinos and Urban Redevelopment in Australia.” Journal of Travel Research 34, no. 3 (1996): 30-36.

Hughson, John. “An Invitation to ‘Modern’ Melbourne: The Historical Significance of Richard Beck’s Olympic Poster Design.” Journal of Design History 25, no. 3 (2012): 268-284.

O’Hanlon, Seamus. “The Events City: Sport, Culture, and the Transformation of Inner Melbourne, 1977-2006.” Urban History Review 37, no. 2 (2009): 30-39.

Welch, Michael. “Penal Tourism and the ‘Dream of Order’: Exhibiting Early Penology in Argentina and Australia.” Punishment & Society 14, no. 5 (2012): 584-615.