Discussion

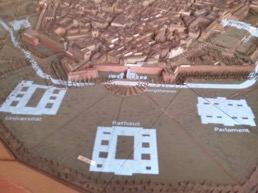

Military conflict has influenced the cityscape of Vienna since the very beginnings of the city. Indeed, Vienna itself began as a Roman military encampment named Vindobona, and it followed the standardized plan that characterized Roman military encampments throughout the Mediterranean world. This legacy persisted throughout the Roman period and into the Middle Ages and beyond, as many of the streets in the modern-day core of the city continue to follow the orientation of the original Roman military camp, particularly its walls. There are fewer records of the city following the collapse of the Roman Empire, but there is evidence to suggest that the site remained continually inhabited at some level until at least 881, when “Vienna” was first mentioned in the historical record (City of Vienna 2020a).

The original roman military encampment that would later become Vienna. City of Vienna. “From the Roman Military Camp to the End of the First Millenary – History of Vienna.” Accessed May 15, 2020.

Despite the presence of ancient fortifications, the modern incarnation of Vienna did not have walls until the beginning of the thirteenth century, having lost them at some point in the intervening years. Leopold V, duke of Austria, captured English king Richard the Lionheart in late 1193 and ransomed him back to the English for 35,000 kilograms of silver (Fuhrmann 1986, 182). These funds were then used in part to construct the first incarnation of Vienna’s walls. The fortifications served the city well during the centuries of conflict with the Ottoman Empire. Vienna first came under siege by the forces of Suleiman the Magnificent in 1529, during which time the centuries-old walls barely held up to repeated attacks. Fortunately for the Austrians, an unusually wet season had created difficult marching terrain, and as a result the Ottomans lost most of their heavy artillery before arriving at the Austrian capital. As a result, they relied on sappers to detonate mines beneath the defenders’ walls, but the Austrians were able to repulse their attempts. Unable to bring the walls down, the Ottoman commander withdrew his forces after little more than two weeks (Sicker 2000, 203-204).

Recognizing the need for better fortifications, the Emperor ordered the building of the second incarnation of the city’s walls, which stood for the next three centuries. These walls turned Vienna into a fortress, with eleven bastions surrounded by a wide, clear field known as a glacis. This was intended to prevent attackers from using any buildings or structures as cover as they approached the walls. This second incarnation of the walls proved vitally important during the second siege of Vienna by the Ottomans in 1683. Unable to raise an army sizable enough to combat the Turkish army, the Austrians found their capital encircled and besieged by between 60,000 and 90,000 enemy soldiers. The lack of heavy siege artillery on the Ottoman side made the walls particularly effective, and the defenders were able to withstand the sapping attempts by the Ottomans for two months, allowing enough time for a 75,000-strong Polish army led by King Jan Sobieski to arrive and break the siege (Hochedlinger 2003, 156-157).

Although these walls proved vitally important during the Ottoman sieges in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the practicality and usefulness of the city’s walls began to shrink as military technology advanced. By the nineteenth century, the walls had largely become an obstacle that physically separated the inner city from its suburbs and hindered the free flow of goods and people throughout the capital. Furthermore, the walls and glacis occupied valuable real estate in a city that was dealing with a burgeoning population and high demand for housing, leading to complaints about wasted space and calls to open the lands up to development (Schorske 1979, 33).

The long history of Vienna’s walls came to an end on December 25, 1857, when Emperor Franz Josef I published a decree that the city’s defensive fortifications be torn down. Pronouncing that “It is my will” (Es ist mein Wille), the emperor stated that

The expansion of the inner city of Vienna should be undertaken as early as possible with a view to a corresponding connection between it and the suburbs, and that the regulation and the beautification of my residence and the imperial capital should also be taken into account. To that end, I authorize the abandonment of the wall and fortifications of the inner city, as well as the trenches around it. (Wiener Zeitung, December 25, 1857)

The construction of the city walls in the middle ages took a literal king’s ransom, but the city found ways to save money on demolition costs (Spielman, 1993, 7-8). First, as the walls were demolished, the material was sold to the general public by the Imperial and Royal State Building Directorate for re-use in construction (Wiener Zeitung, May 1, 1858). With a burgeoning population, housing demand was extremely high, and the re-use of building material was a common practice. There are numerous recorded instances of recycled bricks being used as impromptu construction material, including the erecting of a partition wall made of bricks that had formerly lined a cesspool (Innhauser and Nusser 1878, 5). The city also raised funds through the selling of new plots that would be created once the walls were torn down. Starting in 1859, individuals who could pay for the redevelopment of these plots were given the right to build on them, notwithstanding the 1.5 million parcels – about half of the new land created – that were set aside for the creation of new parks, plazas, streets, and the like. The city was able to raise approximately 220 million Austrian Crowns in this manner (Dmytrasz 2014, chap. 1).

Despite (or perhaps because of) the cost-saving measures, the demolition of the walls was not quickly completed. Work was not commenced until March 1858 (three months after the emperor ordered the walls razed), likely due to the winter conditions, and lasted until 1874 (Dmytrasz 2014, chap. 1). During this time, debates over what to do with the new-found space in the center of the city abounded, including a public competition that attracted 85 architects. One proposal involved keeping the moat around the walls, but laying railroad tracks at the bottom and enclosing them – an antecedent to Vienna’s modern U-Bahn system which, if implemented, could have been the oldest underground metro on the continent, and would have created an subway system in Vienna a century before today’s subway opened in the 1970s (Dmytrasz 2014, chap. 1).

By September 1859, the submissions were judged and the emperor gave his assent for the final plan: it was decided to replace the old fortifications with a new ring road that would encircle the old city and allow for the easy flow of goods and people, fulfilling the requirement laid down by the emperor that connections be made between the inner city and the suburbs. Part of this also had practical military considerations as well. The free flow of people in peacetime also mean the easy flow of troops during times of conflict, such as the uprisings that occurred in Vienna and other cities in 1848. Indeed, at 82 feet wide, the new boulevard would be far too wide for barricading, but wide enough to allow large numbers of soldiers to be easily dispatched to any part of the city. The military even pressed in vain for it to be wider, but with no success (Schorske 1979, 30-31).

The grand opening of the Ringstraẞe, or “Ring Road,” took place on May 1, 1865, with the Emperor and Empress attending a ceremony presided over by the city’s mayor, Dr. Zelinka. In his remarks, the mayor thanked the Emperor for his decision to remove the walls and spoke of Vienna becoming “one of the most beautiful and healthiest cities in Europe” (Wiener Zeitung, May 2, 1865). The mayor did not limit himself to speaking just of the advantages of a new ring road in Vienna’s downtown core, but made positive reference to the larger efforts to improve the urban infrastructure of the Habsburg capital. He particularly highlighted the benefits of the First Mountain Spring Pipeline, which will be detailed in another report (Wiener Zeitung, May 2, 1895).