Cristian Gonzalez

Questions

Where do the poorest residents live in your city? How did they get there? Are there or were there in the past districts of housing built by the occupants themselves?

Discussion

A Bogota mayor in the 1960s described the city as “a city of refugees.” It may sound overstated, but the fact that in 1964 50% of the total population and 70% of those ages 15 to 64 were born outside the city may explain that polemical statement (Torres, 2013, 34). In the first half of the 1900s the average annual growth rate was 3.2%, which quickly increased to 7% on average between 1951 and 1973 (Torres, 2013, 30). In other words, the city passed from 144,000 inhabitants in 1918 to 1,697,000 in 1964 (Torres, 2013, 30). According to Rene Carrasco, this phenomenon occurred mainly due to two factors: first, because of the increase of the fertility rate and the decrease of mortality rate, and second because of the migration from rural areas to the city (58). Alfonso Torres ties the peak of rural immigration between 1951 to 1977 with the “El Frente Nacional,” which was an agreement made by the two main political parties of Colombia, trying to bring peace to the country after many years of political violence (20). Torres points out how this urbanization phenomenon created the beginning of many social movements in Colombia with the barrio (neighborhood) playing the main role in Bogota (20-28).

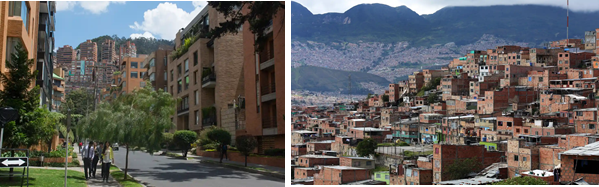

This huge movement of people to Bogota created a new spatial distribution of the city. Alan B. Simmons and Ramiro Cardona describes the migration phenomenon with a focus on what kind of people migrated to Bogota and from where. The authors mainly analyze male migrants, tracing their migration path to Bogota and their spatial distribution in the city based on their skills and income through historical documentation and surveys. Simmons and Cardona report that migrants on average were young men with low educational attainment who came from small towns rather than from rural farms or intermediate cities (170,171). When these migrants, who before migrating had a small portion of land with their own crops and houses, arrived at Bogota, one of their first goals was to find a parcel of land to build their own house (Torres, 2013, 38). As Simmons and Cardona describe, the migrants’ different backgrounds determined their spatial distribution in Bogota. For instance, migrants classified as unskilled and semiskilled settled in the far south of the city, those classified as white-collar settled in the south center, and professionals and upper-income migrants settled in the north (169). Adriana Parias explains in more detail how this pattern of spatial distribution happened in part because of the informal rental market, making the south of the city easier for low-income migrants to obtain a place to live (79). The land was bought legally by investors, but these investors divided the land in illegal plots, which were illegal because those areas of the city did not have public services, hence, they were not allowed to be urbanized (79). This parallel market limited large-scale squatting in Bogota, though people in these informal settlements were still living in very poor conditions (79). Through this process, the northern side of Bogota became formal settlements, where professional and upper-income migrants went, and the south became mostly informal settlements, housing most of the unskilled and semiskilled migrants.

Figure 2. A contrast between north and south urban planning in Bogota. Ella Jessel, 2017

Adriana Parias’s article explains that people in informal settlements live mostly as renters because some externalities have greater influence than their desire to be homeowners. She analyzes in detail the informal housing market, offering clues for improving affordable housing plans from the national government. Parias analyzes the informal settlements of Bogota as a parallel or underground real estate and rental market that formed mostly in the southern parts of the city (79). The high demand for housing and the limited government housing offered to low-income families left a gap that according to Parias was filled by illegal developers who bought cheap land in the outskirts of the city and then sold plots to those disadvantaged populations, creating districts we know today as slums (79-80). Although these lots did not have public services or housing, people figured out how to build their homes: in the beginning they used temporary materials to later be replaced by stronger materials such as bricks. The process lasted between five to ten years (Torres 2013: 52). For this reason, Parias explains that even though the housing deficit (the difference between the number of households and the number of recognized housing units) in Bogota was close to 53% in 1964, only 3% of the total population were actually homeless (82). This low number of homeless was explained by two factors: first by the self-construction that counted 42% of the new housing, and second by the informal rental market where the remaining population found shelter in the form of overcrowding housing (Jaramillo, 1986, quoted in Parias, 2008) Accordingly, more than a half of the people living in informal settlements, which in 1972 represented the 60% of the total population of Bogota, were living in rented housing, confirming Parias’ point that the rental market in informal settlements was strong and profitable despite the poverty of its residents (83).

This city of refugees was formed by many informal settlements with a strong and profitable illegal market. Nevertheless, these neighborhoods had a lot of problems due to the lack of public infrastructure and public services. Torres explained that people living in slums approached those multiple problems in two ways: within the family and as a community (85). Usually, women played a role solving daily issues such as getting clean water and cleaning up the house. Regarding the bigger issues, Torres notes that before the 1960s, residents in the barrios (neighborhoods) randomly started associations with family members and neighbors as an effort to solve some of the issues of their barrios. These unions were the starting point for the later formal neighborhood organizations that would use legal instruments and protests to push local government to improve their well-known deficient infrastructure (85). These movements achieved some positive results, as public works such as sewers, aqueducts, and pavements began to appear in some informal settlements. This development indicated that Bogota had begun to accept these informal settlements as part of the city (85). This social integration was the beginning of a larger protest movement, raising the voice of disadvantaged people working through unions to establish their informal neighborhoods as communities rather than merely physical places (Torres, 2013, 163).

People from the underserved southern neighborhoods found in their unions a successful strategy to be heard by the local government, in an effort to improve their quality of life. However, the pace of those improvements from the public sector was very slow, resulting in increased noncompliance among informal settlement residents. Forero and Molano’s historical description of the timeline and the reasons for the formation of social organizations and protests in Ciudad Bolivar, which is one of the poorest neighborhoods in Bogota, concludes with the civil strike in 1993. In 1983, the Ciudad Bolivar district was created to celebrate the bicentenary of the birth of Colombia’s founding father, Simon Bolivar (Forero and Moreno,2015, 123-124). The area where the new district was created had already been occupied by rural migrants and by migrants from within the city who moved there because of the cheap housing (Forero and Moreno 2015: 124-126). The creation of the district was supported by the national government and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) as an effort to dignify life in the south of Bogota. This district was intended to offer affordable housing to the lowest income families, but, as Forero and Moreno state, Ciudad Bolivar failed to meet its good intentions (124). The new neighborhood grew far faster than the number of affordable housing units given, so again the underground market filled this gap, creating a new slum on the southeastern side of Bogota (123). Nonetheless, the community unions in informal neighborhoods still were their best strength. In 1993, the ten-year old neighborhood with more than 250,000 inhabitants was a neighborhood with extremely high crime and poverty. Because of these deplorable conditions in Ciudad Bolivar, the role of the community unions have gained importance as the only channel that people have to be heard on the local and national stage (134). As a result of these community unions, a strike occurred in October of 1993 in which people blocked roads and highways in the south of the city, demanding immediate action from the local government on issues such as expanding coverage of public services (135). In the story of Ciudad Bolivar, Torres’s point is illustrated, as each neighborhood grew from a mere physical location to a unified community.

SOURCES:

Ella Jessel “’If I’m stratum 3, that’s who I am’: inside Bogotá’s social stratification system”, The Guardian, November 9, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/nov/09/bogota-colombia-social-stratification-system

Forero Hidalgo, Jymy Alexander, and Frank Molano Camargo. “El Paro Cívico de octubre de 1993 En Ciudad Bolívar (Bogotá): La Formación de Un Campo de Protesta Urbana.” Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de La Cultura 42, no. 1 (2015): 115–43. https://doi.org/10.15446/achsc.v42n1.51347.

Parias Durán, Adriana. El mercado de arrendamiento en los barrios informales en Bogotá, un mercado estructural. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, Centro Interdisciplinario de Estudios Regionales, 2008.

René Carrasco Rey. “Barrios Marginales En El Ordenamiento De Bogotá.” Bitácora urbano-territorial 1, no. 8 (2004): 56–63.

Simmons, A B, and R Cardona. “Rural-Urban Migration: Who Comes, Who Stays, Who Returns? The Case of Bogota, Colombia, 1929-1968.” The International Migration Review 6, no. 2 (1972): 166–81.

Torres C., Alfonso. La ciudad en la sombra: barrios y luchas populares en Bogotá, 1950-1977. Segunda edición. Bogotá: Universidad Piloto de Colombia, 2013.