Questions:

What is Singapore’s history of census-taking and surveying? Did it occur in colonial Singapore? How are those surveys taken now? What other types of data does the government collect and track from its citizens? How does the government use this data? Are there critiques on these practices? And has the government acted to respond to these critiques in any ways?

Discussion:

Singapore’s media control and data collection history began just shortly after Sir Stamford Raffles arrived at Singapore in 1819 and declared the island a British trading port. In 1824, Francis Bernard, whom Raffles appointed Chief of Police and Master Attendant, founded Singapore’s premier newspaper, the Singapore Chronicle (Wright 2016). In an astounding foreshadowing of the island’s relationship to censorship for centuries to come, a legislative stipulation from 1824, called “the Gagging Act,” mandated that each newspaper had to be submitted to Governor Raffles for review before publication (The Straits Times 1884). Notably, the year that the Gagging Act was abolished (1835) coincided with the founding of another newspaper called the Free Press (The Straits Times 1884). In 1845, The Straits Times and Singapore Journal of Commerce was established, a newspaper that remains in business today and has served me a great service for primary source documentation on most of Singapore’s history throughout my research on the country.

There are conflicting accounts of Singapore’s first official census. Singapore’s Department of Statistics reports in its Census of 2000 that “Singapore’s first census was taken in April 1871 as part of the Straits Settlement Consensus,” and censuses were conducted every ten years thereafter (Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry… 2002). However, the Singapore National Library Board’s curriculum teaches that the first census in Singapore was taken in 1824 (National Library Board 2019). In fact, Sir Raffles’ colonial government did conduct censuses starting in 1824, and within a couple years they “showed rapid population growth rates on the island” (National Library Board 2019). Given these censuses’ inaccuracy, as they were carried out by the island’s provisional police force untrained in surveying, it is common to count Singapore’s first official census date as 1871. From 1871 onward, a census of the island was conducted every ten years with one exception – during World War II.

A leading expert on Singaporean statistics, Saw See-Hock, published a comprehensive look into “Population Trends in Singapore, 1819-1967” that reveals the reason for the discrepancy covered in the previous paragraph. Saw argues that in assessing Singapore’s censuses, one should separate them by those taken prior to 1871 and those taken after 1871, because the former period’s censuses were conducted so “haphazardly” (Saw 1969). In fact, most records of those censuses have since been destroyed or are unavailable (Saw 1969). Coincidently, in 1872 the colonial government enacted the Registration of Births and Deaths Ordinance and began keeping track of population growth annually (Saw 1969). Interestingly, it is known that in all censuses since 1824, population count by each ethnicity was recorded. (Saw 1969) This is a practice that played a large role in the Housing Development Board of the PAP’s creation of diverse communities, where the HDB used ethnicity counts to set quotas for each community to prevent segregation.

The earlier censuses recorded information on ethnicity, sex, and population count. However, it was not until 1992 that Singapore conducted its first official health survey. A small handful of health surveys were executed in the 70s and 80s, but the 1992 survey “was designated as the first” because it “formed the baseline for subsequent health surveys” (National Library Board 2019). Even in 1988, a Straits Times article reveals that Singapore’s Health Minister required more surveys for the government to put “a finger on the pulse of health among Singaporeans” (Toh 1988). The article describes the previous surveys as more akin to questionnaires about citizens’ approaches to diet and exercise (Toh 1988). The 1992 survey, however, took it a step beyond interviewing individuals about their lifestyles by even measuring their vitals (National Library Board 2019). Data on health surveys prior to 1975 in Singapore is severely lacking.

Shifting the focus to present-day data collection enabled by advanced technology, the question to ask is, what is the government’s approach to Big Data?

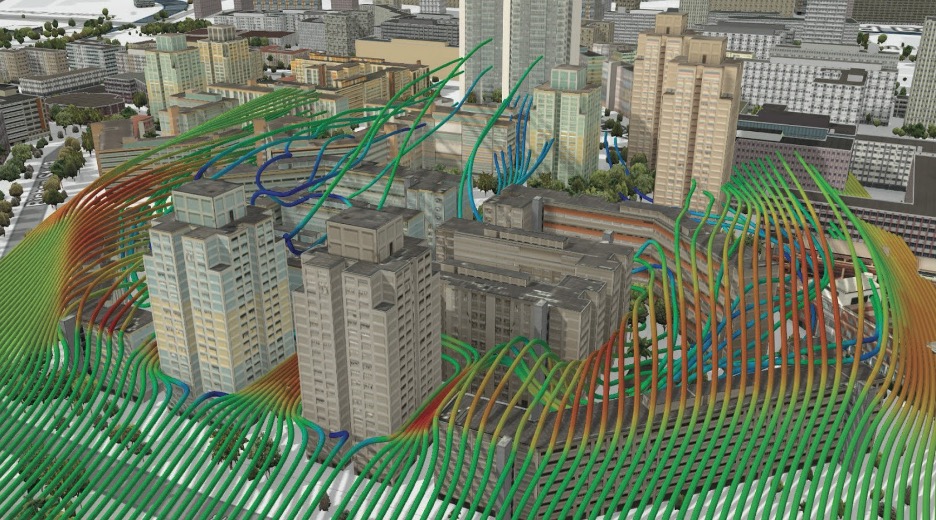

According to the Wall Street Journal, the PAP government of Singapore leads the world’s “most extensive effort to collect data on daily living ever attempted in a city” (Purnell 2016). The effort started in earnest in 2014, when Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong launched the Smart Nation program, which meant the deployment of thousands of sensors and cameras across the country (Poon 2017). The government utilizes this network to “monitor everything from the cleanliness of public spaces to the density of crowds and the precise movement of every locally registered vehicle” (Purnell 2016). One of the centerpieces of the program is to comprehensively map all of Singapore into a replica digital city. The government feeds all its sensor data into the system and can then manipulate simulations to determine best strategies for rerouting bus routes or to model how new skyscraper designs “might affect wind-flow patterns or telecommunication signals” (Purnell 2016). The applications of a big-data network the size of Singapore’s are endless.

The term “big data” can be deceptive in suggesting that the use-cases for the network are limited to macro-level applications like city planning. The network can get as high frequency as monitoring the movement of elderly residents in senior living homes or even individuals swimming in bodies of water to detect drowning (Purnell 2016). The government collects so much data on its citizens that the Smart Nation Program engineers have literally “dubbed the plan, ‘E3A,’ for ‘Everyone, Everything, Everywhere, All the Time” (Poon 2017). Indeed, it is ironic that a country with such radical government authority over data has also passed a national data privacy law, a feat the United States, for example, has yet to accomplish. This dichotomy sets the tone for how the government treats its own authority versus that of the private industry, which will only become more important as the Fourth Industrial Revolution continues.

In 2013, Singapore passed the Personal Data Protection Act (PPDA) to establish a citizen’s data privacy right, a national achievement that not even the United States has attained yet. The PPDA protects citizens’ rights by setting punishments for private organizations misusing or mismanaging their data (Personal Data Protection Commission 2021). However, the interesting part of the PPDA lies in what types of data use it does not protect citizens against. The PPDA does not protect individuals’ data when at or pertaining work, when “acting on a personal or domestic basis,” and most importantly, “in relation to the collection, use or disclosure of personal data” on behalf of “any public agency” (Personal Data Protection Commission 2021). In reviewing the legislative document, it is commendable of the government to establish definitions for terms like “personal data” and to define limits to how much data can be collected and for what purposes. (“Authority” of the PAP government 2012) However, it is hard to discern the meaning of “acting on a personal or domestic basis,” which may lead to loopholes in the PPDA that could enable malicious data mining. Surprisingly, there is a dearth of literature on this gray area.

The government’s free access to private citizens’ data raised concerns in 2020 when the government released its cutting-edge contact tracing app for Covid-19, TraceTogether. Within the first few months, only 20% of the country had downloaded the app. The government responded to this low adoption rate by announcing it would not lift restrictions until downloads reached at least 70% of the population (Lay 2020). The announcement boosted adoption to around 80%, but the issue of data privacy came to the forefront of conversation when, in January, the PAP admitted to allowing law enforcement to use the app’s data for criminal investigations (Jamie Tarabay 2021). The PAP has also used citizens’ data in an unprecedented fashion to implement a “coordinated [social] media strategy” using “digital campaign tools [that] enabled the PAP to overtake the opposition parties in expanding social network” (Tan 2020). Indeed, Singapore’s vast, advanced data collection systems have granted the PAP government unprecedented power.

Today, the PAP takes one of the most hands-on approaches to data collection in the world. Akin to the CCP, the PAP practices censorship and maintains the position that any data useful to the government will be made available to the government. While the cameras and sensors that make up much of Singapore’s Smart Nation program are also used in cities like London and New York, the idea that the PAP could use pandemic-related contact tracing data for criminal investigations exemplifies its extreme reach in the cyber domain. On the other hand, Singapore holds its private industry to high standards and protects the consumer from egregious or malicious use of individuals’ data. Indeed, this dichotomy between the powers in data collection the government enjoys versus the restrictions of collection by private industries dominates the “Big Data” conversation today.