Cristian Gonzalez

Questions

Does your city have a single overall plan? When was it made and with what aims? How much was realized?

Discussion

The articles and books reviewed describe the urban development of Bogota from 1800 to the early 1900s. This urban development was influenced by national independence from Spain in 1819, and then in 1884 by the introduction of the trolley as public transportation. In the year 1801, the city had 173 blocks and 21,394 inhabitants. Additionally, Bogota was the political and demographic core of Nueva Granada (Colombia today) but remained a small city as compared with similar cities in the 1800s, such as Lima and Buenos Aires (Martinez 151).

Mejia’s (2012) book describes the history of Bogota from 1536 to 1604 that according to the author, this age marked the foundation of Bogota and its consolidation as a colonial city. Romero’s historical compilation of seven chronicles from travelers of different countries during the XIX century in Bogota, reports, among other things, the people’s culture, and customs in the 1800s. Comparing what Mejia (2012) concludes was the city’s shape in 1557 with the 1800s city, the city’s basic shape basically remained the same, a checkerboard, with the Plaza as its core (Figure 2). In other words, the city grew in area adding new square blocks but kept the same urban fabric (139). Romero ,based on travelers’ description of the city in 1830, notes that most of buildings in Bogota had one floor, and a few had no more than two. A special characteristic of those houses with two floors, which were the houses of the wealthiest families of Bogota, were their balconies. Mejia’s (1999) book provides a study of the urban history of Bogota after the Nueva Granada independence from Spain, marking the beginning of the modern city. Mejia’s (1999) city description notes that building facades of Bogota were very simple, without ornaments, meaning no more than a wall with windows and the entry door (148). However, due to the poor street conditions because of the potholes and waste and the lack of cultural and social activity at night, architectural ornament was reserved to the interiors where Bogotanos spent most of their time (148). One of the few outdoor activities of the people of Bogota during the first half of the 1800s was going to the Plaza, or the altozano, as the locals called it (192). Romero describes the Plaza as the social core of the city, where fresh fruits were sold and where inhabitants from all socioeconomic backgrounds converged.

Figure 2. These images show a comparison between the 1557 and 1797 colonial layout of Santafe, which was the colonial name of Bogota, in order to illustrate their similar shapes. Sources: (left) Mejia, 2012- (right) Paredes, 2000

Mejía (1999) explains that after the milestone fact of the independence from the Spanish, which was a process that lasted roughly ten years, from 1810 to 1819, some changes started to happen in the landscape of Bogota (151). Those changes happened slowly while the new republican order was gaining power (196). Trying to distinguish itself from the colonial past, the new Republic began changing the names of the plazas and streets (198). The names of colonial streets were changed for the names of the provinces of Colombia and the names of the most important independence battles (202). Thereafter, the empty plazas of the colonial ages turned into ornamented plazas with trees and civic statues (200). For instance, the first civic statue placed in a plaza in Colombia was the figure of Bolivar, the main founding father of Colombia (198). The statue of Bolivar was unveiled on July 20, 1846, which is the Independence Day of Colombia, in order to strengthen patriotism toward the new republic among people of Bogota and Colombia (198).

Martinez’ work explains how Jews, through their entrepreneurial actions, played a role in shaping the current urban characteristics of Bogota in the late 1800s and in the early 1900s. The book also explains the differences between the real estate market before and after Jewish intervention. The last quarter of the 1800s, from 1870 to 1900, more clearly marked a new urban landscape of Bogota. According to Martinez, the constant rural migration to Bogota had been one of the most important factors that allowed the city to maintain its influence in the region both during the colonial era and during the Republic (164). In 1847, the city governor and the council tried to expand the urban area of Bogota beyond the colonial limits; however, that expansion, which was encouraged by Colombia president Tomas Cipriano de Mosquera, ended in the 1860s (169). The Mosquera plan included designating the western part of Bogota for an orderly urban expansion, including building bridges, wider roads, and plazas, but the plan was only partially implemented (170). In the following decade, other urban initiatives emerged, but this time from the private sector. A group of businessmen, tired of the city’s slow growth, proposed the construction of sewers, theaters, electrical systems, and new roads in order to hasten development (170). Because of the 1876 civil war, this plan could not be implemented, but the initiative led the council to adopt the first urban code of Bogota in 1875 (171). These initiatives tried to update the undeveloped city to the new technologies of the 1800s. However, the pace remained slow, and only after 1882, when the train and the trolley came to Bogota, did some urban development projects begin to progress more quickly (167).

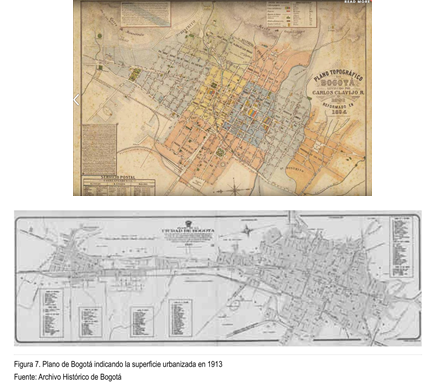

Ricardo Montezuma depicts the trolley of Bogota as a technological innovation that changed the urban character in the late 1800s, based on evidence such as demographic statistics, urban areas, and maps. Moreover, Montezuma shows a clear link between the trolley and the introduction of new urban concepts in Bogota. Along this line, Montezuma’s book argues that when the trolley was introduced in the city, the urban changes started to happen at a faster pace. The layout of Bogota turned into a lineal city (south to north) after the first trolley line was implemented and the urban area rapidly grew 45% from 1884 to 1900, breaking up the slow urbanization process of the previous eighty years (Figure 3) (86). Unsurprisingly, 80% of that new urban area was built along the first trolley line (87). 45% of the total urban growth of the 1800s was the product of only six years of building (87). For the first time since Bogota’s founding, the landscape of the city changed its compact checkerboard shape, based on square blocks, for a bigger urban pattern based on neighborhoods, formed by rectangular or square blocks of different sizes and inspired by the English garden city movement (89-90). In addition, the roads were organized into a hierarchy in which certain roads were bigger and longer than others depending on their use (90).

Besides the trolley, Montezuma notes that the lineal growth of the city and the influence of Anglo-Saxon architecture placed the neighborhood at the core of the new urbanization of Bogota (91). According to Goossens, this new foreign influence in the early 1900s inspired the realization of a map depicting the existing city as well as the projection of the future city (62). Groossens asserts that this new urban plan, which was made by a public employee, was excellent in architectonic, economic, and urban terms (64-65). Unfortunately, the plan was not implemented at all, but it served as a guide for the location, construction, and renovation of many urban facilities during the period of 1925 to 1950 (66). Thus, there are today some illustrations of this urban planning effort evident in the streets of Bogota. Bogota continued its search for a better urban plan. O’Byrne’s article explains that despite the multiple efforts to plan the city, the city never implemented any of the urban models proposed (195). In another effort, the city hired Le Corbusier in the late 1940s. The Le Corbusier plan included regional integration and some demolition as part of his downtown renovation idea (198). As with previous plans, the Le Corbusier plan was not implemented. According to O’Byrne, the Le Corbusier plan has been wrongly judged by history, in part because it was not well analyzed, academically or technically, by many of its enemies who downplayed the plan (199). Though there have been some efforts to plan the city, the urbanization of Bogota for most of the 1900s was ultimately more organic than planned.

Figure 3. The above image illustrates the 1894 layout of Bogota when the lineal city started to appear. The below image (1913) illustrates the lineal expansion of Bogota to the north following the first line of the trolley (Paredes, 2000: 87)

SOURCES:

Goossens, Maarten. “Ideas para la planeación de la ciudad futura. Bogotá, 1917-1925.” Bitácora urbano-territorial 28, no. 1 (2018): 61–70. https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v28n1.59707.

Martínez Ruiz, Enrique. Quinta Sión : los judíos y la conformación del espacio urbano de Bogotá . Bogotá, D.C: Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, 2018.

Mejía P., Germán. Los años del cambio: historia urbana de Bogotá, 1820-1910. 1. ed. Santa Fé de Bogotá: Centro Editorial Javeriano, 1999.

Mejía Pavony, Germán Rodrigo. 2012. La Ciudad De Los Conquistadores: Historia De Bogotá 1536-1604. Bogotá: Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Montezuma, Ricardo. La ciudad del tranvía. 1880–1920: Bogotá: transformaciones urbanas y movilidad. Volumen 1. Editorial Universidad del Rosario, 2008.

Romero, Mario Germán. Bogotá en los viajeros extranjeros del siglo XIX. Villegas Editores, 1990.

Santiago Londoño Vélez. “Bogotá ayer.” Boletín cultural y bibliográfico 28, no. 28 (1991): 131–34.

Paredes, Claudia C,. Instituto Distrital de Patrimonio Cultural. La vida privada de los parques y jardines públicos, Bogotá, 1886-1938. 2020. https://issuu.com/patrimoniobogota/docs/parques_web_. and Montezuma, 2008, p87