QUESTIONS:

How did modern writers, artists, or filmmakers document street life in Vienna? How did they define or express its modernity?

DISCUSSION OF SOURCES, DATA AND ANALYSIS:

From the 13th century to the mid-19th century, the city of Vienna had not undergone any radical changes in its development. Vienna was one of the last European metropolises to tear down its city walls, which it did following public pressure after the revolutions of 1848 (Winkler 2021, 3). Through a decree issued by Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph in 1857, the newly vacant space was to be repurposed for public use in what would become the Ringstrasse. Historians seem to agree that the transformation of Vienna’s medieval glacis to the open Ringstrasse marked a turning point for the city’s modernization both politically and socially. However, what was meant to be a bridge between the old and new became a representation of the simultaneous social isolation and overstimulation of the modern urban experience.

The Ringstrasse was a grand boulevard encircling the inner city of Vienna, and with a breadth of 56.89 meters, the street itself was one of the widest avenues in Europe at the time (Frisby 2010, 234). The ring was divided into eight subsections, each marked by a different monumental building intended to serve the needs of the public, including the university, city hall, parliament, the opera, stock exchange and museums. Despite the civic importance of the buildings, their spatial placement and the wide swaths of empty stone and pavement between them made it a difficult place for pedestrians to be. In his 1981 book on fin-de-siecle Vienna, Carl Schorske (67) described the buildings as “alternate centers of visual interest” floating unorganized and unrelated in the spatial medium. Viennese architect Camillo Sitte believed that the city should be planned so that it is “picturesque and psychologically satisfying” by making the citizens feel both secure and happy (Schorske 1981, 95). In his opinion, the Ringstrasse violated this principle as a “cold sea of traffic-dominated space” and the “isolated, free-standing buildings failed to create intimate public squares through architectonic containment and principles of enclosure” (Watkins 2008, 178; Winkler 2021, 21). People felt dwarfed by the Ringstrasse’s imposing buildings and wide, open streets in which they played second fiddle to vehicles. Frisby and Schorske both note that it was around this time that agoraphobia, the anxiety or discomfort associated with feeling trapped in a public space, began to be diagnosed (Frisby 2008, 24). Schorske (96) further relates agoraphobia with the changing dynamics between Vienna and its residents by arguing that dwarfing of people in the space led them to lose their sense of relationship to the buildings and monuments. The ring shape encouraged the constant, circular flow of traffic, which led to an increase in the pace of everyday life. Watkins (176) argues that the flaneur was evicted from Vienna with the city’s reorganization and redirection of people into controlled, quick-moving patterns of motion.

Along with agoraphobia in response to the reorganization of movement within the city, neurasthenia, or overstimulation, emerged as a psychological effect on the residents of Vienna. Overstimulation was considered the common, “typical disease of the urban city dweller, who was said to suffer from overexcited senses” (Payer 2007, 779). Sounds of traffic and other activities extended later into the night leading to increased complaints of insomnia, and noise was recognized as a “sanitary evil” (Payer 2007, 779). Between the time of the Ringstrasse’s construction and the First World War, the city experienced a period of rapid urbanization. Vienna’s surface area expanded from 55.4 to 275.9 square kilometers and its population grew from 431,000 to about two million inhabitants after the incorporation of the suburbs (Payer 2007, 775). Along with the increase in population came the increase of traffic and activity, changing not only the pace of everyday life, but noticeably the soundscape of the city as well.

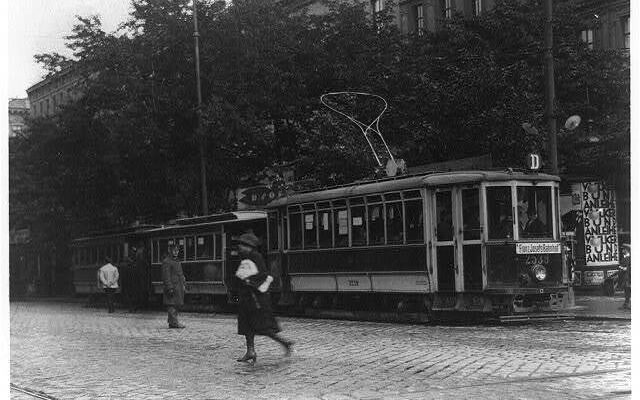

Gruber et al (300) point to a rising tension between the street as an urban living space, where city dwellers could meet with others, conduct business, eat or drink and the street as a transportation space, where vehicles began to crowd out the people. The sounds of humans and animals became enmeshed with a constant hum of traffic such as horse-drawn carriages, electric streetcars and their accompanying bell signals, cyclists, and later cars and motorcycles. The layout of the city diffused sound differently as well, with the buildings forming “street canyons” that amplified sound and made it difficult to get “one’s bearings acoustically” (Payer 2007, 776). To protest the increase in noise pollution, a group of Viennese professionals led by Hugo von Hofmannsthal founded a chapter of Theodor Lessing’s Antilärmverein or Anti-noise Society in 1909. The chapter collected various complaints and petitioned the city to criminalize excess noise (Payer 2007, 782). Payer notes that the group’s “refusal to put up with noise” was seen as a neurotic weakness or inability to adapt to modern life, but doctors would later endorse a direct connection between the increase of noise and rise in nervous behavior in the city (Payer 2007, 779).

Artists, especially those who looked to the city for inspiration, were particularly aware of the psychological impacts of modernization. Besides being involved in combating anxiety-inducing aspects of city life in the public sphere, they were reflecting the new relationship between the modern city and the individual through their work. Architect Adolf Loos published a collection of essays in 1931 reflecting on the impact of Vienna’s transformation on the city. In “Footwear” he writes, “walking as slowly as people did in earlier times would be impossible for us today. We are too nervous for that” (Loos 1931, 29). Loos’s modern architecture also reflected his take on changing city life and social interactions. While Georg Simmel attributed the city dweller’s cold demeanor to aversion or antipathy, Loos interpreted this a self-protection measure against overstimulation in “the urbanite’s [refusal] to reveal anything to [his fellow man]” (Watkins 2008, 130). This idea would influence one of his most famous works, the Villa Müller, in which the façade of the building was plain, white with straight edges and no embellishment or lining of the windows, completely opposite of what was in style for the time. Inside, functions were demarcated not by simple walls and doors, but by angled planks and windows at various heights that played with the light and dimensionality of space in ways that were currently unavailable in the public realm. Like the modern urbanite on the street, this house revealed nothing of its interior state.

Music, which had always been a key component of Vienna’s identity, also changed as a result of modern transformations. Music historian Alexandra Hui argues that “conceptions of sound sensation shifted”, in part due to “psychophysical assault from the outside world” (Hui 2012, 237). Ordinary citizens complained of irritation from the sound of organ grinders from street performers and the music of gramophones and pianos that could be heard through walls (Payer 2007, 785). Professional musicians used their own experiences of the city as inspiration. In her analysis of his artistic productions and documentations of composer Arnold Schoenberg’s friendship with contemporaries such as Loos, Holly Watkins examines the effects that life in fin-de-siecle Vienna had on the long-term resident. Watkins argues that “the shifting manifestations of an urbanized consciousness” could be found in Schoenberg’s music (Watkins 2008, 126). “depiction of spiritual waywardness” in Schoenberg’s oratorio Die Jakobsleiter reflected his observations and concerns of the “alienation and soulless movement generated by modern urban planning” (Watkins 2008, 178). She relates its opening line to modern principles of efficiency and motion in which individuals are “estranged from each other and communal spiritual ideals”: ‘whether right, left, forward or backward, uphill or downhill, one has to go on without asking what lies before or behind’ (Watkins 2008, 178).

The sounds of voices and other expressions of community “disappeared into quiet lanes and side streets, the interiors or apartments, shops, market halls, and inns, and recreation and pleasure areas on the outskirts of the city” (Payer 2007, 789). Some of this shift from public living to private living was an intentional form of self-preservation in response to overstimulation, as in the case of Loos’ modern architectural designs. However for the most part, it seems as if previous space for urban living on the street level in Vienna was co-opted for transporting people between modern living spaces in an orderly fashion. This transformation completely changed how people viewed one another and themselves within the city, as well as raising questions that are still relevant today about finding the right balance between human and functional needs in public spaces.

SOURCES:

Frisby, David. 2008. “Streets, Imaginaries, and Modernity: Vienna Is Not Berlin.” In The Spaces of the Modern City: Imaginaries, Politics and Everyday Life, 21-57. Princeton University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1j66706.6.

Frisby, David. “The Significance and Impact of Vienna’s Ringstrasse.” In Manifestoes and Transformations in the Early Modernist City, edited by Christian Hermansen Cordua. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2010.

Gruber, Carmen, Kathrin Raminger, Takeru Shibayama, and Manuela Winder. “On the Vienna Corso: Changing Street Use and Street Design Around the Vienna State Opera House 1860–1949.” The Journal of Transport History 39, no.3 (2018): 292-315. DOI: 10.1177/0022526618790443.

Hui, Alexandra E. “The Bias of ‘Music-Infected Consciousness’: The Aesthetics of Listening in the Laboratory and on the City Streets of Fin-de-Siecle Berlin and Vienna.” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 48, no.3 (Summer 2012): 236-250. DOI: 10.1002/jhbs.21546

Loos, Adolf. 1931. Ornament and Crime. Translated by Shaun Whiteside. Penguin Classics.

Payer, Peter. “The Age of Noise: Early Reactions in Vienna, 1870-1914.” Journal of Urban History 33, no.5 (July 2007): 773-793. DOI: 10.1177/0096144207301420.

Schorske, Carl E. 1981. Fin-de-Siecle Vienna: Politics and Culture. New York: Vintage Books.

Watkins, Holly. “Schoenberg’s Interior Designs.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 61, no.1 (2008): 123-206. DOI: 10.1525/jams.2008.61.1.123.

Winkler, Tanja. “Vienna’s Ringstrasse: A Spatial Manifestation of Sociopolitical Values.” Journal of Planning History 20, no.3 (2021): 269-286. DOI: 10.1177/1538513220943146.