Questions

How has war affected the history of St. Petersburg? Are its marks visible?

What kinds of reconstruction projects has the city had?

What is the relationship between reconstruction and war memories?

The Siege of Leningrad and War Memories

The history of the city St. Petersburg is a history of transformations and memories. One of the most famous battles that happened on this soil is the Siege of Leningrad (Leningrad was the city’s name at the time) in World War II. Lasting from September 8, 1941 to January 26, 1944 (Voronina 2018, 81), this historically significant blockade greatly changed Leningrad. Scholars later have interpreted and helped present the multiple faces of this post-war city and its people. This is a tale of trauma, recovery, remembering and forgetting.

In her book that concentrates on post-war Leningrad/St. Petersburg after the Siege of Leningrad, Lisa A. Kirschenbaum tells a story: in late 1943, after visiting Leningrad, Alexander Werth, a British journalist and Petersburg native, claimed that the city looked well-preserved (Kirschenbaum 2006, 121). This statement of Werth fails to depict a comprehensive image. First of all, during the blockade, German bombs and artillery damaged many historical structures as well as city infrastructure (Kirschenbaum 122). Secondly, “Leningraders, however, measured destruction not only in terms of damage to the city’s icons but also in terms of the disorder, damage, and emptiness of their everyday places.” (Kirschenbaum 122) In summary, Kirschenbaum argues that the marks of the siege might not be obvious to the outsiders who did not suffer the blockade themselves, but they were clearly visible to the Leningraders because those marks had imprinted on their everyday lives. Through analyzing Lidiia Ginzburg’s Notes of a Blockade Person, Emily Van Buskirk highlights another important impact that is rarely mentioned: the harsh blockade environment even triggered anger and hatred among family members (Van Buskirk 2010, 284). In other words, the blockade not only damaged buildings and streets but also relationships and mental health. In fact, both Kirschenbaum and Van Buskirk highlight the psychological trauma that Leningraders experienced during and after the blockade. The similarity between the two sources stresses the severity of this issue. Compared to the physical destructions that were still apparent, the mental effects were less visible yet even heavier.

How did the official reconstruction projects during the post-war period address and treat the issue of trauma and memory? Interestingly, a number of scholarly works provide the same answer by indicating a sense of heroism that became the mainstream at the time. Here are some examples: the ideology of socialist realism transformed the blockade into a heroic event instead of merely labeling it as traumatic (Voronina 81-82). The framers of the 1943-1947 reconstruction plan originally worked on shifting the city core southward, but they changed their mind due to the recognition of the Leningraders’ sacrifice for their city (Ruble 1990, 50). Although the word “heroism” is not present in this example from the work of Blair Ruble, the reason behind the cancellation of the original plan was certainly the appreciation for heroic spirit. The concentration on heroism heavily influenced the reconstruction projects. “A survivor of the blockade, Kamenskii proposed restoring and beautifying the city as the most appropriate form of commemoration. The program of healing paradoxically removed all traces of war from the cityscape in the name of memorializing ‘heroic events.’” (Kirschenbaum 115) After comparing the sources, it is obvious that their responses to the question all lead to the same conclusion, showing the official emphasis on the celebration of victory and heroism, and at the same time, the neglect of trauma and memories.

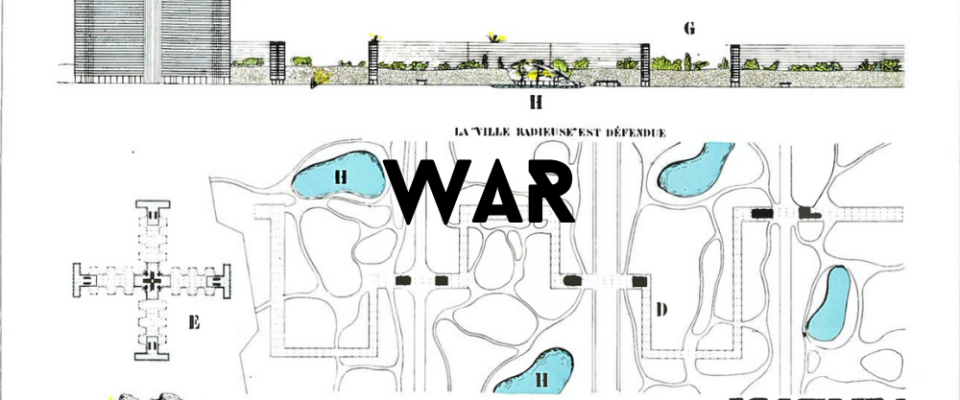

One important mission of the reconstruction projects, as suggested by Kirschenbaum, was to establish a beautiful and again, heroic city. Following the plans, more than 700 million rubles were invested during reconstruction from 1945 to 1946, and in the traditional city center, 1.6 million square meters of housing was built. A few prospect (which means “street” in English) were renamed. Victory parks and the Kirov Stadium were constructed. Nonetheless, despite all these successes, the officials ignored major social and economic trends (Ruble 50-51). Among all the reconstruction projects, victory parks are the best example that symbolizes both “the beautiful city landscape” and “the celebration of victory and heroism.” Besides Ruble, other scholars like Voronina and Kirschenbaum also highlight their significance. One of the illustrations in Kirschenbaum’s book shows that the shell craters at the Moskovskii Victory Park were transformed into ponds (Kirschenbaum 138). It is difficult to feel the marks of the siege by merely looking at the parks and other reconstruction projects, but it does not mean that the trauma no longer existed. Scholarly sources highlight the conflict between reconstruction projects and war memories, which is also the conflict between the state and the general population.

Catriona Kelly writes, “In the context of city landscapes, ‘memory’ is likely to be just as indelibly associated with editing, adjustment, and rupture: the statues that have disappeared, the place-names that have changed, and the buildings that have been demolished, or altered beyond recognition.” (Kelly 2014, 1) This evaluation of city landscapes and memories perfectly reflects the situation of post-war Leningrad. The original goal of the reconstruction projects was indeed to heal the city, but these projects eventually led to forgetting. Historian Sheila Fitzpatrick believes that after the war, the Soviet regime intended to tighten, instead of loosening, controls on the society (Kirschenbaum 141). Kirschenbaum then concludes that the government’s control over urban space erased both the marks of the war and local commemorations (Kirschenbaum 147). Furthermore, Voronina points out that there are different types of memories. She believes that the purpose of establishing memorial complex in post-war Leningrad was to reflect the military memory that highlighted heroism and bravery. Meanwhile, however, the story of civilians became less important (Voronina 88). In other words, it is inaccurate to say that reconstruction projects did not help preserve memories. By establishing monuments and victory parks, the officials did preserve the memories of victory and heroism. It was the traumatic war memories of the general population that went missing.

Yet, there is no complete forgetting. Even though they encountered strict state control over local recollections, common people in post-war Leningrad found their ways to hold on to their memories. In spite of the different focuses of sources, a lot of them mention how Leningraders guarded their post-war lives. For example, focusing on the return of Leningraders after the war, Elizabeth White states, “[A]lthough the Soviet government used its powers of territoriality to control and monitor the return, there were spaces and gaps where people could evade this control.” (White 2007, 1159-1160) Leningraders found their path. They did not have specific places to commemorate, but their memories could not be fully erased since those memories had been closely associated with their daily life (Kirschenbaum 149-150). Kirschenbaum point out that even though post-war reconstruction of Leningrad did not efficiently address their traumas and memories, residents continued living in the city to remember and carry on.

Leningraders could not visualize themselves without looking back to the blockade (Kelly 4). The devastating Siege of Leningrad had a long-lasting influence. This is a tale of both Leningrad and its people after the blockade. This is also a tale of war memories from both official and public perspectives, which contradicted to each other, yet at the same time, coexisted.

Bibliography

Kelly, Catriona. St Petersburg: Shadows of the Past. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014. https://www-jstor-org.proxy.library.georgetown.edu/stable/j.ctt5vktn3.

Kirschenbaum, Lisa A.. The Legacy of the Siege of Leningrad, 1941-1995 Myth, Memories, and Monuments. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Ruble, Blair A.. Leningrad: Shaping a Soviet City. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft500006hm/.

Van Buskirk, Emily. “Recovering the Past for the Future: Guilt, Memories, and Lidiia Ginzburg’s Notes of a Blockade Person.” Slavic Review 69, no.2 (summer 2010): 281-305. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25677099.

Voronina, Tatiana. “From Socialist Realism to Orthodox Christianity: ‘Blockade Temples’ in Saint Petersburg.” Laboratorium: Russian Review of Social Research 10, no.3 (2018): 79-105. DOI: 10.25285/2078-1938-2018-10-3-79-105.

White, Elizabeth. “After the War was Over: The Civilian Return to Leningrad.” Europe Asia Studies 59, no.7 (November 2007): 1145-1161. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20451432.