By using real estate as the framework through which to view the development of Mombasa as a city, one can assess not just the physical location and condition of housing and property across the city, but also the social, economic, cultural, and legal dynamics present. What follows is a temporal survey of Mombasa’s housing provision during the twentieth century, in particular for the growing urban African population, who at least under colonial rule were the most politically and economically marginalized group within the city. A conceptual foundation will first be laid with a brief history of customary land tenure and colonial land laws through to the post-independence era in Kenya. Two articles from Hay and Harris provide a comprehensive view of colonial housing systems in Mombasa, with particular attention given to the role of employers in the provision of these living spaces. Hunter Morrison’s description of Swahili housing in the city is laden with detail about this distinctive feature of housing in Mombasa and is especially pertinent to the discussion of opportunities for property ownership for urban Africans during the twentieth century. Stren’s Housing the Urban Poor in Africa extends the temporal frame beyond the colonial era to reveal how Mombasa’s housing politics reflected a wider tangle of local, national, and international political tensions. Finally, Rakodi, Gatabaki-Kamau, and Devas’ article demonstrates how certain trends identified by the other authors have continued in Kenya’s post-independence era, none more so than the inconsistent and inadequate provision of housing for the poorest of Mombasa’s residents, the growing urban African population.

The underlying factor which determined the provision of housing in Mombasa and across Kenya was the system of land rights and tenure. Literature on land governance in Kenya, especially that which focuses on colonial policy, tends to look at the whole country rather than providing analysis specific to individual cities. Nonetheless, these studies are valuable contributions to understanding the legislative and regulatory context in which property development and housing provision in Mombasa occurred. Okoth-Ogendo’s article examining the nature of the African Commons as a property system provides a description of pre-colonial land distribution in Kenya. Dependent on subsistence agriculture and pastoralism systems, land was governed based on adherence to collective principles and values while remaining conscious of future needs and the need to protect against external threats (Okoth-Ogendo, 2002: 108). During colonization the 1902 Crown Lands Ordinance was passed, stipulating that any vacant land became Crown land and was thus available for transfer to European settlers (Home, 2012: 190). As identified in Onguny and Gillies’s survey of literature on land conflict in Kenya, access, and management of land had shifted from social ownership to private ownership systems (2019). Home’s analysis of “Colonial Township Laws and Urban Governance in Kenya” unpacks the East African Protectorate’s decision in 1906 to pursue the codification of laws pertaining to non-natives (European settlers and Indians) as it befitted their expansion and accumulation of political power in the region (2012: 177). The pre-colonial customary land tenure, with its variable land parcels, did not provide the certainty that the colonial regime desired in order to expand cash crop production and encourage agricultural investment (Onguny & Gillies: 2019). Within this developing system of governance, a native commissioner, an appointed British colonial official, would represent African interests but there was no actual representation of Africans as they were thought to be “not fit to govern” the lands where the colonial regime dominated (Home, 2012: 177). The laws and practices in other British colonies, especially the Cape Colony in South Africa, provided inspiration and tested templates for colonial officials in Kenya in how to manage the land and African populations (Home, 2012:178).

The implementation of the 1902 Crown Lands Ordinance enabled the transfer of five million acres to the European settlers by 1914, and by 1963 when Kenya gained independence over a million acres were in the hands of European settlers (Home, 2012: 190). This was in part because the 1902 ordinance was extended in 1915 to vest all public lands in the Protectorate, including all lands occupied by native tribes, in the Crown. This same expanded ordinance also effectively created freeholds for white settlers who were now able to acquire 999-year leases from the colonial government (Home, 2012: 190).

Hay and Harris’s discussion of urban housing in Kenya prior to 1939 highlights various factors central to the development of colonial policy towards housing, how it was implemented, and the responses from those subject to such policies (2007). Hay and Harris signal the importance–and the frequent omission in previous studies on colonial Kenya’s urban housing situation–of employers of African workers in urban areas in the narrative of construction, provision, maintenance, and control of housing in colonial Kenya. Together, municipalities and employers were responsible for meeting the housing demands of all Africans. Even though Africans were the absolute majority population across Kenya’s urban areas, they lived at much higher densities in comparison to other groups in the city and so did not occupy as much territory and, as mentioned in earlier reference to the development of the governance system in Kenya, had no direct political power (2007: 505). Examining the role and performance of employers provides a window into the shifting perspectives and tensions between the Colonial Office in London and the colonial government in Kenya which were hashed out through the design and delivery of urban housing.

Employers began to play a central role in the narrative of Kenya’s urban housing policy because colonial policies required them to. In 1923, a White Paper from the Colonial Office in London stated that “the interest of African natives must be paramount” as part of the wider policy of “Dual Mandate,” which articulated two, albeit contradictory goals: firstly, to exploit colonial resources for imperial benefit, and secondly through a concept of “trusteeship” to preserve and incorporate African political and social institutions, largely in rural Kenya (Hay & Harris, 2007: 506-8). In many parts of Kenya, this presented a challenge: colonial administrators and counterparts in London wanted to preserve the African ways of life in the countryside, but the necessities of colonial development–maintaining trade and ensuring European domestic comfort–created a demand for African labor in the towns (Hay & Harris, 2007: 509). While the colonial regime’s underlying goal was to control African labor in both urban and rural Kenya, the practical realization of promoting African interests was articulated through developing economic opportunities and improving the living conditions for the African populations in the urban areas (Hay & Harris, 2007: 509). As such, an urban housing policy for Kenya emerged that was in opposition to the notion of a permanent presence of Africans in Kenya’s urban centers: accommodation would only be needed on a temporary basis to house the African men who were employed in the central urban areas, such as Mombasa (Hay & Harris, 2007i: 196). The colonial regime often considered the rural villages in other parts of Kenya to which these employed men were connected to be their permanent residences.

The responsibility to house this influx of Africans to towns was in the colonial government’s hands, but practically sourcing and administering this housing fell to individual municipalities and employers. While the colonial government stipulated that employers provide housing for their workers, there was little interest or incentive to do so, in part because the available contracts for land from the municipalities were often short-term, which disincentivized investment in durable housing (Hay & Harris, 2007: 511 & 518). The general trend was that employers did very little, if anything, to meet their statutory responsibility. This is best exemplified by the statement from the Medical Office of Health for the Municipal Board of Mombasa, who in 1939 commented that most employers “neither know or care” where their workers lived (Hay & Harris, 2007: 513). Even the most basic provision of bachelor housing was often left wanting. The local municipalities plugged the gaps, although Mombasa’s Native Commissioner argued that by the late 1930s even the local and national governments had “virtually ignored” their responsibility to house the influx of African workers (Hay & Harris, 2007: 513). The anomalous and exemplar case of an employer providing a living situation for their employees was the Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbours Administration (KUR), which took responsibility for every town’s permanent and casual workers on its books. By 1945, KUR had housed 1,816 of its 2,547 African workers in Mombasa, many of whom had been rehoused in permanent structures (Hay & Harris, 2007: 516). Yet even KUR did not house 30 percent of its employees.

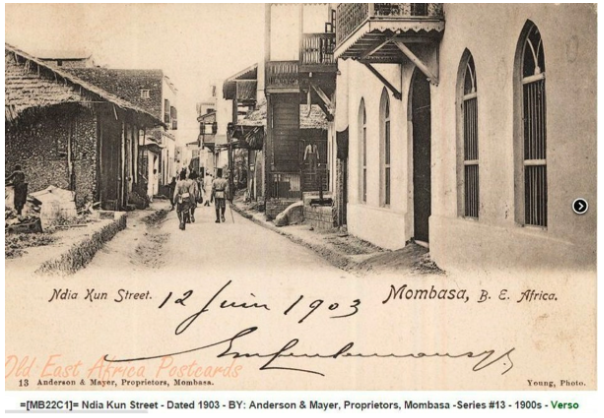

The shortage of housing for African workers in Kenya’s urban areas had far-reaching consequences. Many colonial officials cited a lack of both actual and adequate housing as a major contributing factor to social unrest across the country. This was certainly true in Nairobi in the 1920s, as the city’s African population rose from roughly 15,000 people in 1920 to 28,000 in 1930, by 1939 the population likely exceeded 41,000 (Hay & Harris, 2007: 519). Mombasa, however, had an experience distinct from Kenya’s other cities. Much older than many other cities in the country, Mombasa also had a small European population relative to its large, intermingled community, which consisted of a hybrid of Swahili, Arab, and South Asian residents. However, the divergence of Mombasa’s experience is largely due to the city leadership’s response to its economic reality. Unlike Nairobi, Kisumu, or Eldoret, private interests were able to build inexpensive housing in Mombasa. Additionally, when dealing with the city’s informal settlements, Mombasa deviated from the colonial norm of simply demolishing the low-income housing, which was considered cost prohibitive. Instead, the Director of Land Surveys, A.G. Baker, advocated widening the streets and improving existing structures (Hay & Harris, 2007: 528). Despite this, the city’s sanitation system was “deplorably bad,” according to a commission that surveyed Mombasa in 1939 (Hay & Harris, 2007: 520).

A further distinctive feature of Mombasa’s response to the demand for housing for the growing urban African population was the permission, and indeed at times incentivization, of the construction of “village layouts” of Swahili houses by private landowners and builders. While these private groups were able to rent out the Swahili houses and ultimately earn a profit, the municipal government serviced the dwellings. Commencing mass construction in 1927, within fifteen years the fifty-seven “village layouts” that had been sanctioned housed several thousand people and were considered by Gordon Wilson, the official “government sociologist,” to be “the most effective short-term solution to African housing in the urban areas of Kenya” (Hay & Harris, 2007: 528).

The salience of housing continued to grow in Kenya’s colonial policy discourse, and by the mid-1940s was at the top of the colony’s health and social agenda. Indeed, Hay and Harris say it was themost important issue in Mombasa (2007i: 203). After 1945, there was a massive push to build more housing in the urban centers like Nairobi and Mombasa, but also more widely across the country. Between 1948 and 1949, the government built over 1600 housing units across the country, and local authorities and public agencies built a further 3181 (Harris, 2007i: 209-10). The aforementioned Gordon Wilson conducted a housing and family survey of Mombasa in 1957 and found that while this wave of housebuilding occurred on the coast, it was significantly more modest compared to the quantity built in Nairobi (Harris, 2007i: 210). While most houses lacked indoor plumbing, these dwellings diverged from those built two decades prior because now schools and washstands were in proximity. Previously, houses had been built with only the bachelor worker in mind. Now, it was clear that families were part of the growing urban African population (Harris, 2007i: 210). However, there was still a lack of attention to the traditions and customs of the residents as family dwellings were often in the same plots as the bachelor houses which raised “serious social problems, especially among tribes who have rigid rules of sex segregation,” according to Gordon Wilson’s African assistant (Harris, 2007i: 213).

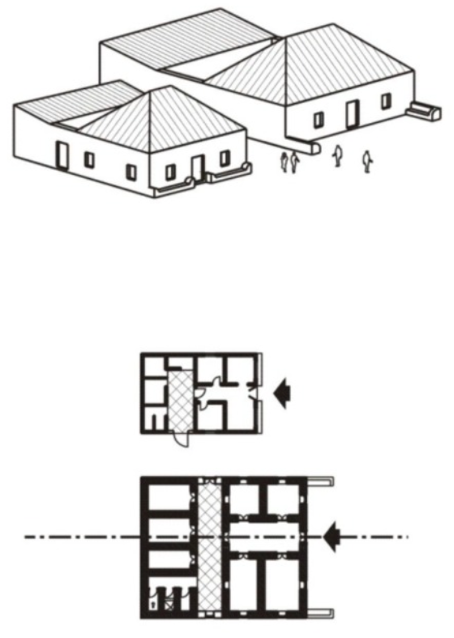

By the 1950s, the resistance within colonial policy towards a permanent African urban presence had diminished even further as the government expanded its housing program to include owner-occupation for Africans in various urban areas around Kenya. The Swynnerton Report (1954), which was part of the colonial response to the Mau Mau Uprising, recommended the creation of a class of African property owners in trust lands (native areas which were controlled by colonial land boards), with the ultimate objective of eliminating customary land law (Home, 2012: 191). One of the pilot areas was Changamwe, a suburb of Mombasa, which included financial and technical assistance programs that aided those purchasing property who would have otherwise been unable to afford it (Harris, 2007i: 213). The Swahili houses, as described by Morrison, were one of the few options available for Africans in Mombasa to own a property. The layout of Swahili houses meant that owners could rent out the front rooms and outhouses of the property, providing a steady income to the owners (Morrison, 1974: 279). The materials used in Swahili housing were inexpensive, versatile, from the area, and could be used easily to construct a basic framework. Furnishings and further adornments to the property could be added as time went on and financial resources allowed (Morrison, 1974: 279). Additionally, the ease of access to the building materials was essential to “a cycle of maintenance and renewal,” such as replacing the roof or repairing the walls, which extended the lives of the Swahili houses (Morrison, 1974: 279).

Hunter Morrison’s analysis of the housing systems of Nairobi and Mombasa provides a detailed description of the “Swahili” houses in and around Mombasa. At the time Morrison published his article in 1974, sixty-five percent of Mombasa’s population lived in Swahili housing, some of these houses having been constructed at the turn of the twentieth century (1974: 278-9). While the houses themselves may have been a twentieth-century addition, the Swahili housing market predated British town planning and operated in accordance with the Sunni principle of tenancy-at-will. This system of land tenure would initiate an informal agreement between the landlord and house builder in which the latter would pay a premium as well as a monthly rental fee for the land. No papers would be exchanged but the landlord would issue receipts that were accepted by the municipal authorities (Morrison, 1974: 279). Most of the Swahili properties that were developed in Mombasa during the first half of the twentieth century were located on the mainland, rather than Mombasa Island.

The works discussed focused not only on Kenya’s years under colonial rule but call attention in particular to the role and impact of colonial policy. Richard Stren’s Housing the Urban Poor in Africa fruitfully explores other dynamics at play in Mombasa’s housing situation. Stren provides a snapshot of the tangled relationships between the local, national, and international authorities who engaged with Mombasa’s housing policy in the post-independence years in Kenya. By explicitly looking at the socio-economic dimensions of Mombasa in the post-independence years, Stren demonstrates the crystallization of Kenya’s class structure. Mombasa’s housing system was reflective of Kenya’s wider urban development strategy in which the interests of the poorest residents of urban areas were castigated while the demands of the “dominant bourgeoisie” were met. This class divide was compounded by ethnic rifts that had been present for many years in the city, especially as they demanded greater representation in the local government (Stren, 1977).

Migrants from the up-country clashed with the established coastal communities over access to employment and resources within Mombasa. These rifts were stoked by the national and municipal authorities, whose intention to create a stable African urban middle class (a reversal of colonial policy from only a few decades prior) frequently secured large sums of money and resources for middle and upper-income groups. For example, from 1965 the Mombasa Municipal Council invested in public housing schemes, which benefitted these wealthier income groups. In his analysis of public housing, Stren reveals too how the politics and policy machinations of Mombasa’s housing system were reflective of a wider trend in Kenya’s domestic politics from 1963 to the mid-1970s. It is not clear if Mombasa was unique, or if this was the case for many urban areas and their municipal councils, but Stren argues that local politics became the site through which national power struggles, interparty competition, and trade union negotiation in Kenya were worked through (1977).

Rakodi, Gatabaki-Kamau, and Devas round out this brief literature review on the history of the housing situation in Mombasa, coming closer to the present day. The overwhelming theme from Rakodi, et al, when read in conjunction with the other authors is of continuity with the trends identified by Hay and Harris, Morrison, and Stren. Onguny and Gillies demonstrate that the continuity of land regimes’ connection to local and Kenyan national politics was not passive as land rights have successively become a mechanism of fostering political relationships, linking elite “landlords” across the country to the central state (2019). As such, governments have become increasingly reluctant to engage in land reform to address historical irregular land allocations (Onguny & Gillies, 2019). The economic and political environment of Mombasa was conducive to expansive private land ownership, which Hay and Harris credit the construction of cheap, and therefore more accessible, housing during the colonial period. However, Rakodi, et al, highlight that the long-term consequences of this widespread privatization of land have been the relatively limited proportion of land under public ownership. The private market had given way to a land rental system and the development of multi-roomed bungalows (Rakodi, et al, 2001: 167). The controls the municipality tried to exert over land development during the colonial era were still in existence with little more success, as unauthorized subdivision and development of property continued across Mombasa (Rakodi, et al, 2001: 167). The Sunni legal principle of “tenants-at-will” appeared to be thriving and was becoming increasingly commercialized as rents within this sub-market fluctuated according to the distance from the Central Business District and the maintenance of the property (Rakodi, et al, 2001: 168). Ethnic and class tensions, with their associated economic inequalities, were continuing to simmer. More broadly, across Kenya public lands, like forestland, were illegally distributed for personal gain and attempts to hinder the reorganization and operations of land institutions (Onguny & Gillies, 2019). These rifts were further inflamed by the Kenyan national political system invoking ethnic and tribal identities to coalesce support (Rakodi, et al, 2001: 158).

Overall, the main element of continuity across the century that these authors cover is that many of Mombasa’s poor residents continue to live in sub-standard conditions in informal settlements. Basic infrastructure remains inconsistent, and even when it is present it is inadequate. Official recognition and approval of these informal settlements are variable. Echoes of the colonial regime’s reluctance for the development of an African urban class can still be heard. The terms and conditions adopted by the city’s political leaders and others across Mombasa have contributed to many poor residents seeking out loans or selling their property when they could not maintain pace with the costs of new construction (Rakodi, et al, 2001: 166). The proportion of Mombasa’s residents who are owner-occupiers dropped from 29 percent in 1983 to 23 percent in 1989, and now most tenants rent from private landlords (Rakodi, et al, 2001: 168). Although, the residents of Mombasa have broken with this continuity in one meaningful way: the presence of an African urban population is now certainly a permanent fixture of Mombasa city life, even if their residences are not.

Bibliography

Alison Hay & Richard Harrisi, “New plans for housing in urban Kenya, 1939-63,” Planning Perspectives 22, vol. 2: 195-223.

Alison Hay & Richard Harris, “‘Shauri ya Sera Kali’: the colonial regime of urban housing in Kenya to 1939,” Urban History 32, no. 3 (December 2007): 504-530.

Robert Home, “Colonial Township Laws and Urban Governance in Kenya,” Journal of African Law 56 no. 2 (2012): 175-193.

Hunter Morrison, “Popular Housing Systems in Mombasa and Nairobi, Kenya,” Ekistics 38, no. 27 (October 1974): 277-280.

H. W. O. Okoth-Ogendo, “The Tragic African Commons: A century of expropriation, suppression and subversion,” Cape Town: Institute for Poverty Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) (2002). http://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/8098/The%20Tragic%20African%20Commons.pdf?sequence=1

Philip Onguny & Taylor Gillies, “Land Conflict in Kenya: A Comprehensive Overview of Literature,” The East African Review 53 (2019).

Carole Rakodi, Rose Gatabaki-Kamau & Nick Devas, “Poverty and political conflict in Mombasa,” Environment & Urbanization 12, no. 1 (April 2001): 153-170.

Steyn, Gerald. (2015) “The Impacts of Islandness on the Urbanism and Architecture of Mombasa,” Urban Island Studies, http://www.urbanislandstudies.org/UIS-1-Steyn-Mombasa.pdf.

Richard E. Stren, Housing the Urban Poor in Africa: Policy, Politics, and Bureaucracy in Mombasa (Berkeley: University of California, Institute of International Studies, 1977).