Questions: How was Manchester impacted by World War II? What was the main redevelopment plan? What was actually implemented from that plan? What was adopted outside of the plan? Why was there a difference between imagination and execution?

Manchester, UK:

The 1940 Blitz, The City of Manchester Plan 1945, and Manchester’s Post-War Redevelopment

Throughout its history, the city of Manchester has faced various natural and man-made changes that have altered the layout of the city. One of the most significant periods this can be seen is in 1945. Manchester was a main player in World War Two and a target of the 1940 Christmas Blitz, leaving the post-war city government to deal with a decimated city desperately in need of reconstruction. While the people of Manchester proved themselves to be resilient and recovered quickly following the end of the war, the city’s efforts to transform itself were slow and characterized by luxurious, unrealistic dreams of “what could be” if the city wiped the slate clean. The City of Manchester Plan 1945 left ambitious city leaders blind to the harsh realities facing the city and, instead, a much more modest and reasonable plan was ultimately adopted in its place. The main problems that required attention in post-war Manchester were a lack of housing, heavy traffic in the city center, air pollution, and inadequate public transportation.

War Hits the City

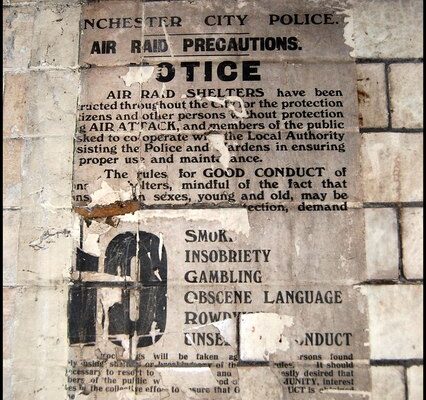

In December 1940, during the Second World War, citizens sheltering in their homes in Manchester awoke to a major bombing campaign consisting of over 450 tons of explosives and about 2,000 incendiary bombs raining down on the city. As a result of the aggressive German air raids, which took place in the consecutive nights leading up to Christmas, an estimated 684 people died and more than 2,000 were injured (“The Manchester Blitz”). Accounts documenting the bombing, included those from local museums such as the Imperial War Museum, detailed how the raid left communities flattened, warehouses and factories demolished, and families fractured, with a significant amount of the damage taking place in compact commercial centers and residential areas, causing fires to easily catch, and spread over those two nights (“The Manchester Blitz”). Despite the devastating effects of the bombing, now known as the “Christmas Blitz,” the citizens of Manchester were not ill-prepared. As described in the chapter “Total War” by author Stuart Hylton in his book A History of Manchester, the city began preparation for the war in September 1939 with additions of bomb shelters, fire stations, hospitals, and other ad hoc arrangements including evacuation plans (Hylton 2003, 203). The people of Manchester knew they had to prepare as their industrial city was an obvious target for bombings due to its economic power during World War Two. The likely bombing target was manufacturing infrastructure, including aircraft manufacturers, engine factories, and other necessary industries aiding the war effort. Other physical infrastructure, such as the inland port and transportation, including railways and highways, were also known targets for bombing campaigns.

An Ambitious Plan for the Future

Leaders and city authorities faced a massive challenge following the end of the war in 1945. Post-war Manchester found itself in a state of disarray. As explained by Hylton, the bombings left a drastic reduction in housing stock, with about 60,000 dwellings deemed unfit after the war and 53,000 homes overdue for demolition since before the war (Hylton 2003, 203), a significant homeless population, and a city physically scarred by the war. These post-war problems were also exacerbated by the lack of financial investment in the city during the war due to the need to put the money elsewhere that left the whole of the city’s infrastructure in disrepair.

In response to these factors, leaders in the city responded with Manchester’s first development plan, the City of Manchester Plan 1945. This proposal is considered by some, including Manchester-based writer and tour guide Jonathan Schofield, to be “perhaps the most ambitious re-imagining of a city ever conceived” (Schofield 2017). The principal mind behind the ambitious 300-page fully illustrated plan was City Surveyor Rowland Nicholas, who saw a city that needed to transition gracefully from war to peace. Nicholas wrote a bold yet comprehensive plan that he hoped would be unbound by existing legislation to enact a large-scale city transformation (Rowland iii). Using the destruction caused by the Blitz as a starting point and featuring photographs highlighting the extensive damage of the city, the plan stated, “it was the Blitz that awakened public interest. But it was not the Blitz that made planning necessary… there is an opportunity for rebuilding; for designing structures that will be worthy of our city” (“City of Manchester Plan 1945” 6-8). The plan proposed the “‘thinning out,’ zoning, and rebuilding of the densely built inner areas” (“City of Manchester Plan 1945” 7), with the main objective of the plan to “enable every inhabitant of this city to enjoy real health of body and health of mind” (“City of Manchester Plan 1945” 8). The plan, as summarized by Schofield, comprised aspects attempting to develop and make the city focused on the “town center.” This trend was popular in the UK during the 20th century, as explained by Peter Larkham, with a marked increase in buildings and areas devoted to municipal administration and culture common after the war, essentially part of the movement from single town halls to entire civic centers. This plan envisioned “a city centre of wide tree-lined boulevards [and] of fresh air” with focus on different sectors including zoned areas for commerce, housing, industry, education, and recreation. The visionaries also wanted “a city freed from the gloom of the pre-World War II Great Depression, liberated from the filth of nineteenth century industrial grime, a rational city” with the main idea to make Manchester a flagship for peacetime Britain and an example that others could copy when designing their cities of the future (Schofield 2017). This idea was not novel to Manchester, however, as explained by Jeffry M. Diefendorf, where war was an extraordinary opportunity that provided many planners, such as Nicholas, to reshape cities in ways that could better harmonize the built and natural environments (Diefendorf 2009, 171).

Many aspects of the plan were unrealistic. The proposal included, for example, detailed schemes for different neighborhoods in the city planned down to the last individual house, leaving little interpretation for the individual. The planners, however, saw this plan as an attempt to achieve the ambition of the rational modern city they envisioned, so they proposed that many of the older buildings had to be replaced. This included the mills, warehouses, offices, banks, pubs, and housing, as the plan essentially attempted to wipe the slate clean of the old, war-destroyed Manchester. The design focused on a new vision, a new path, one where humans could use the mass destruction of the war and reimagine cities in the way they wished, not being restrained by existing infrastructure, architecture, or planning mindsets from years past. This ideological mindset is especially captured in a quote in the introduction of the plan which states, “We are entering upon a new age: it is for us to choose whether it will be an age of self-indulgent drift along the pre-war roads towards depopulation, economic decline, cultural apathy and social dissolution, or whether we shall make it a nobler, braver age in which the human race will be the master of its fate”(“City of Manchester Plan 1945” 200). Within this quote, readers are given a peek into the ideals of the time as reimagining the city was the name of the post-war game.

Manchester’s Town Hall still stood in the city center following the war, yet an illustration by the well-known architectural artist J.D.M. Harvey for the Manchester plan showed the Victorian Gothic of Waterhouse’s Town Hall replaced by a low, plain Scandinavian-influenced building with an elongated tower (Larkham 2004, 11). This demolition was suggested as the designers attempted to envision a more modern city with less intricate architecture, even if it meant destroying the historic landmark. This proposed style, as explained by author Colin Cunningham in his book Victorian and Edwardian Town Halls, was very outside of the traditional buildings found in the city prior. This instead was a vision that ignored the hope to develop infrastructure spanning out from the typically Victorian town hall as seen in a number of city plans at the time. In these plans following WW2, the structures were, in essence, a continuation of the civic grandeur demonstrated by the period of town hall construction in the Victorian and Edwardian periods reflecting place-promotion and civic boosterism (Cunningham 1981).

Cost was a secondary factor when detailing the city plan, as the total expenditure of the city planning was not calculated. Instead, the creators of the plan gave the excuse that it was “difficult and meaningless to assess in monetary terms what the community would gain from the planning in terms of enhanced municipal income, time saved, better health, and higher productivity” (“City of Manchester Plan 1945” 7). Finally, the plan, other than being too ambitious, idealistic, and uniform, essentially shunted aside the working-class citizens that it was created to supposedly benefit because solving the desperate social and economic problems faced by those especially affected by the war was hardly considered in the plan. Many of the plan’s provisions were not passed or implemented but did spur national interest. Hylton writes that the plan was “held to be a model approach for the entire nation” (Hylton 2003, 214) as a model of the idealistic rebuilding of cities.

The Realities of City Redevelopment

Actual post-war planning differed significantly from The City of Manchester Plan 1945 and the plan was rarely referenced in documents explaining the actual formation of Greater Manchester, which was, as explained by Manchester city scholars Richard Brook and Martin Dodge, possibly reflective of the plan’s ambiguous status at the time and its limited legacy in the makeup of contemporary Manchester (Brook and Dodge 2013). The immediate priority for leaders following the war was building homes for the displaced and slum clearance. While slum removal was mentioned in the initial plan, the references only regarded replacing them with the envisioned sturdier infrastructure with little mention of the citizens living within and the conditions of the dwellings. However, the City Council, recognizing the serious problem of limited and inadequate housing, immediately after the war restarted its pre-war efforts at clearing slums and aimed to clear 7,500 slums dwellings that were overflowing due to the lack of housing in the city driving many to the slums of the city. Slum removal further tied in with housing as the people they removed from the teeming slums had to find a place to live, the reason they initially came to the slums in the first place. The city fell 1,000 short of its target, which prompted a more ambitious program that would later be implemented in 1960. Authors Peter Shapely, Duncan Tanner, and Andrew Walling, in their article “Civic Culture and Housing Policy in Manchester, 1945-79” explore local housing policies that were influenced by Manchester government initiatives, funding patterns, local expert opinions, and civic and cultural values that significantly influenced the lives of public sector tenants. These policies began with the consideration that civic leaders were not satisfied with merely building industrial-style high-rise buildings, instead giving initial preference to the 1945 Manchester Plan’s vision with cottage style housing arrangements to create living communities with unique senses of identity (Shapely, Tanner, and Walling 2004, 417). However, it was difficult to turn this housing vision into a reality considering the “lack of money, land, building materials, and labor” (Shapely, Tanner, and Walling 2004, 419). Instead, the city opted to compromise between the low-rise ideals and high-rise alternatives and therefore agreed to house people in low-level houses outside the city in what became known as “overspill housing” as they faced pressure to clear slums and reduce waiting lists for housing. Eventually, the city succumbed to the industrial and cheap high-rise model they attempted to avoid immediately after the war. Architects designed, manufactured, and built the high-rise block buildings poorly and the buildings did not meet the psychological or social needs of the people living in them (Hylton 2003, 216). These housing issues would not be properly addressed by the city until 1994.

Manchester’s post-war years saw other planning initiatives in the city. One of the most noteworthy ideas for the industrial post-war city plagued with air pollution was the concept of a smokeless zone, an idea that was supposed to be implemented in Manchester in 1938 before World War Two interrupted the plans (Longhurst and Conlan 1945, 352). As new buildings were built in the city following the war, they immediately became blackened with air pollution and people in the city continued to suffer a high death rate from respiratory diseases (Hylton 2003, 217). To counter this, the council created a private act to create smokeless zones in 1946, and the first smokeless zone covering 104 acres of the city center was introduced in 1952, a surprising but necessary act for the health of the Manchester citizens considering the other pressing needs in the city. Despite the zone creation efforts, the city’s air quality continued to be poor, pushing the council to renew efforts that eventually led to the Clean Air Act of 1956, aiming to reduce air pollution by 80 percent over 20 years. By 1981, virtually all the city was covered by smokeless zones and air pollution had fallen drastically, resulting in the improvement of health outcomes in the city, as had been envisioned initially in the Manchester Plan.

Manchester also sought to improve the important infrastructure of the city. A pre-war terminal named Ringway was released by the British Air Force for commercial civil aviation in 1946 allowing Manchester to become not just an international airport but also an intercontinental airport by 1953 (Hylton 2003, 212). City leaders also brought public transport to Manchester’s streets via tram services in the 1960s. Traffic was also removed from parts of the city center including Market Street, Albert Square, St Ann’s Square, and King Street. Ultimately, despite the fact that the Manchester Redevelopment Plan was not implemented, Manchester was able to find its way into the future forging a path that worked for the city, but it was not without struggle. Through the exploration of Manchester’s war history, one can see the idealistic idea of the city and city center that had been imagined in the redevelopment plan but also how these plans were dashed due to the extent of damage and the needs of citizens that the city had to meet.

Bibliography:

Brook, Richard, and Martin Dodge. “Symposium Report: The Making of Post-war Manchester,

1945-74: Plans and Projects.” Cities@manchester Blog. June 04, 2013

https://citiesmcr.wordpress.com/2013/06/04/symposium-report-the-making-of-post-war-manchester-1945-74-plans-and-projects/.

Cunningham, Colin. Victorian and Edwardian Town Halls. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul,

1981.

Diefendorf, Jeffry M., and Jeffry M. Diefendorf. “Wartime Destruction and the Postwar

Cityscape.” In War and the Environment Military Destruction in the Modern Age, 171-

88. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2009.

Dodge, Martin, and Joe Blakey. “City of Manchester Plan 1945.” Issuu.

https://issuu.com/cyberbadger/docs/city_of_manchester_plan_1945.

Hylton, Stuart. A History of Manchester. Chichester: Phillimore, 2003.

Larkham, Peter J. “Rise of the ‘Civic Centre’ in English Urban Form and Design.” URBAN

DESIGN International 9, no. 1 (2004): 3-15. doi:10.1057/palgrave.udi.9000109.

Longhurst, J.W.S., and D.E. Conlan. “Changing Air Quality in the Greater Manchester

Conurbation.” Transactions on Ecology and Environment 3 (1994): 349-56.

Nicholas, Rowland. City of Manchester Plan. London, 1945.

Schofield, Jonathan. “The Biggest Manchester Redevelopment Plan of All Time.” Confidentials.

July 7, 2017.

https://confidentials.com/manchester/manchester-plan-1945-the-biggest-manchester-redevelopment-plan-of-all-time.

Shapely, Peter, Duncan Tanner, and Andrew Walling. “Civic Culture and Housing Policy in

Manchester, 1945-79.” Twentieth Century British History 15, no. 4 (2004): 410-34.

doi:10.1093/tcbh/15.4.410.

“The Manchester Blitz.” Imperial War Museums.