Questions: Where do most citizens of Kyiv live? How did that housing get there? What is being done to address abandoned housing?

The modern cityscape in Kyiv is defined by crumbling identical panel walls and exposed wiring, with citizens still living in Soviet architecture long past its prime. These homes, once a solution to the postwar housing crisis under Nikita Khrushchev, now serve as a reminder of the follies of mass production. Although envisioned as a utopian solution to Stalin’s wasteful spending, low-quality khrushchevka neighborhoods are now pejoratively known in Kyiv as “Khrushchev’s slums.”

Housing shortages had plagued the Soviet Union since its inception, with the policy of abolishing private ownership of real estate and redistribution of nationalized properties meaning that citizens were forced to live in poor, cramped conditions (Gunko et al. 2018, 290). Housing specialists Maria Gunko et al. conduct a review on the main waves of construction methods in the Soviet era, which went hand-in-hand with evolving leadership.

The first wave, defined as a period from the 1920s to 1930s, introduced the first instance of communal housing. Very few buildings existed from the tsarist era by then, as they were destroyed either due to fires or communist efforts to stamp out tsarist history. In the early 1920s, no one construction style had been chosen for the yet nascent socialist state, and cities within the Soviet Union still had their own architectural identities. Pre-war buildings in Kyiv were carefully crafted to be functional, with floor plans including multiple bedrooms, nurseries, and separate libraries to accommodate large communal housing (Poddubnaya and Shaidiuk 2021). This resulted in long buildings which needed many entrances for individuals to access their apartments from within a complex.

This independent era of Kyiv’s communal housing ended with Joseph Stalin coming to power. Gunko et al. describe a second housing wave from the 1930s to the 1950s known as the “Stalin period,” which was marked by a sudden shift to uniform 4-9 storied apartment complexes. Such complexes, known as stalinka, were only located in prestigious parts of Soviet cities and intended for the elite; meanwhile, much simpler communal high-rise units were built for working class people on the outskirts of towns, creating a distinct class disparity (Gunko et al. 2018, 293). Stalinka were noted for their grandiose and often avant-garde postconstructivist style, one heavily criticized by Stalin’s successors. Due to being established for the elite, stalinka are now remembered as a symbol of excess, inefficiency, and labor intensive work.

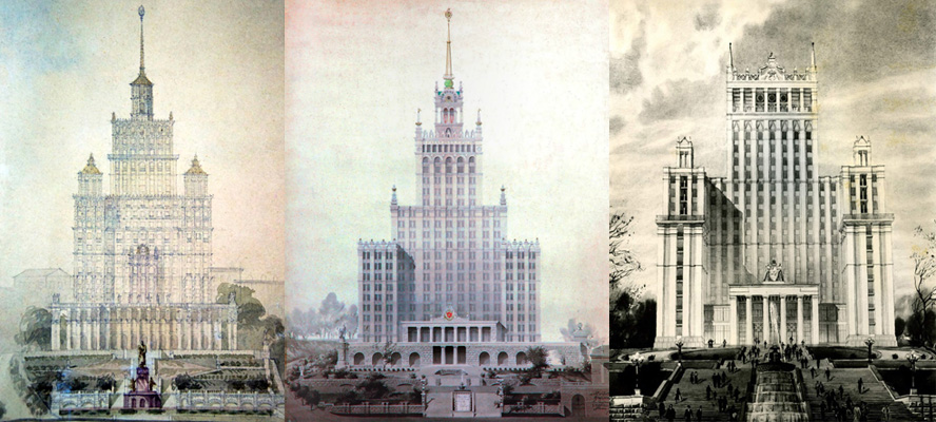

One of the most memorable structures assembled during the Stalinist era is the Seven Sisters in Moscow, a series of high-rise buildings in the form of government infrastructure, universities, and luxury hotels. Historian Sofiya D. Tugarinova writes an analysis of these buildings, noting that functionality was sacrificed in favor of composition and a need for the silhouette of the city to reflect dominance (Tugarinova 2016, 38). Stalin’s successor Nikita Khrushchev explained these ambitions by writing “[Stalin] said, the foreigners will come, walk around Moscow, and we do not have high-rise buildings. And they will compare Moscow with capitalist capitals. We will suffer the moral damage” (Tugarinova 2016, 30). Following Stalin’s death, Khrushchev made a dramatic change to incorporate minimalist designs in his reconstruction of Kyiv.

It is here that Gunko et al. point to the post-war era as the third wave of Soviet construction from the mid 1950s to late 1960s – a period marked by a transition to mass housing. Kyiv needed to be completely rebuilt following aerial bombings during WWII. Soviet authorities’ use of the scorched earth policy ensured that nothing of Kyiv could be valuable to the German army during the Battles of Kyiv, leaving the city barren. In 1953, a group of architects were employed by the Soviet regime to abandon the neoclassical Stalinist style and completely change the city’s landscape (Koveshnikova 2014, 61). Simplified designs became emblematic of buildings whose development was halted during WWII, seen below in the planning of the Hotel Ukraine in the center of Kyiv. What once resembled decorative turrets were smoothed, the structure grew more block-like, and blatant symbolism of Stalin’s regime – such as a monument out front – were scrapped from plans.

Source: 1940-1950 architecture articles by Boris Erofalov and Semen Shyrochin

Once Khruschev came to power, there was no longer an architectural separation between elite housing and working-class quarters. Now everyone lived in identical conditions, with new estates being built in large blocks designed to house roughly 300 inhabitants (Gunko et al. 2018, 293). Using colorful mosaics resembling Ukrainian folk motifs made Kyiv more distinctive, but residential buildings were all the same manufactured using prefabricated panels made from concrete known as “panelky.” This material proved to be efficient and cost-effective (Veryovki et al. 2019, 79).

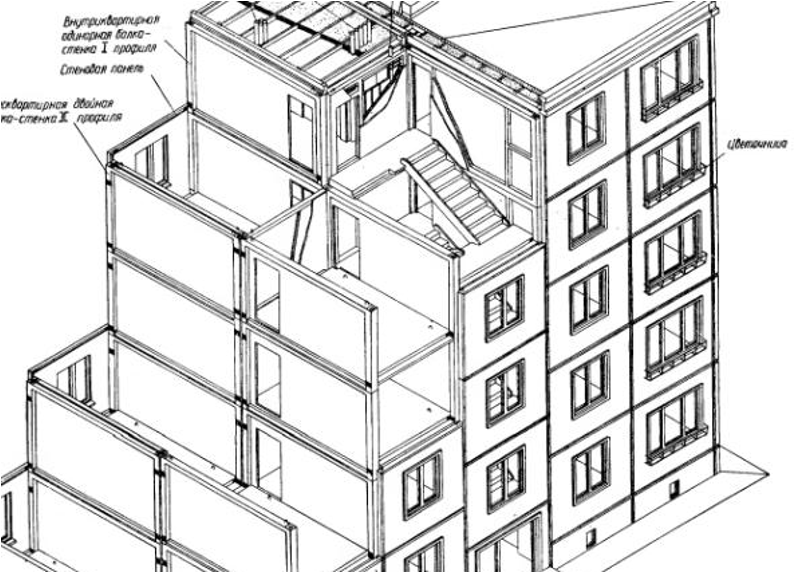

Maximizing cost-effectiveness became the cornerstone of Nikita Khrushchev’s leadership. He was heavily inspired by the works and ideology of Le Corbusier, the Swiss-born French architect renowned for designs which relied on rationalization, standardization, and mass production. Ksenia Choate writes that Khrushchev’s architecture plans echoed Le Corbusier’s writings on how form follows function, seeking to rid the Soviet Union of any excesses under Stalin (Choate 2010, 8). The Soviet people needed a utilitarian place to sleep and eat in between their contributions to the future of communism, and the more compact a building could be constructed for this purpose, the better.

Source: Nikolay Erofeev, Open Left

Thus, the khrushchevka was born. These were typically 5-story (“pytietashky”) panel homes designed to be built quickly and cheaply. Old neighborhoods were demolished and rebuilt at a frightening speed, with 10% of the entire housing stock of the Soviet Union rebuilt with khrushchevka in 25 years between 1959-1985 (Erofeev 2014). Khrushchevka were built in long rows to make it easier for cranes to access them, with groups of rows being titled “micro-districts” (мікрорайон) (Dobrova 2017, 32). To create these mass production projects, the labor force was brought over from the countryside. These people then moved to occupy the new housing districts permanently, displacing the hundreds of thousands of lives lost in Kyiv during WWII.

Rooms were small, soundproofing was poor, and terrible insulation made winters freezing and summers boiling hot. Philipp Meuser and Dimitrij Zadorin write on the immensely poor reputation that Nikita Khrushchev’s khrushchevka acquired, calling them notorious for shoddy construction and depressing urban environments (Meuser and Zadorin 2016, 15). Ksenia Choate also discusses the macabre sacrifices that citizens needed to make in the name of frugality. Fancy woodwork and carvings were scrapped as a cost-saving measure, as were the widths of shared spaces and stairways. Stairs were so narrow (there were no elevators), in fact, that it was impossible for a resident of a khrushchevka to carry a coffin downstairs without needing to walk into a neighbor’s apartment to turn it sideways (Choate 2010, 90).

However, despite the flaws of this form of minimalism, there were also some moral benefits. Modernist Soviet architecture specialist Nikolay Erofeev notes that the aforementioned problems were all trifles for Soviet people who finally saw an alternative to previous communal housing. The new khrushchevka apartments lacked thick walls and balconies, but they provided a new opportunity to people to settle in individual units with their nuclear families. Khrushchevka not only assisted in the post-war housing crisis, but gave peoples’ lives a new sense of purpose (Erofeev 2014). Moreover, micro-districts in Kyiv were created with accessibility for citizens in mind, making sure that schools, grocery stores, playgrounds, and department shops were never more than 500 meters away from any residential dwelling. Although citizens did not own private property, everything within a micro-district was for public use (Dobrova 2017, 32).

While historians tend to write Soviet mass housing off as a dystopian failure, the architectural community today instead views it as a unique phenomenon worthy of study due to the altruistic goals of Soviet-era urban planners. Anna Dobrova, another Kyivan architect, points to how khrushchevka acted as a microcosm of Soviet society. Civic engagement would create cities that functioned on a completely new set of laws antithetical to western models based in capitalism and exclusion. Urban planners of the post-war era truly believed that they were creating an innovative world based on equity for all citizens (Dobrova 2017, 30). Over time, planners also realized that more public spaces needed to be created for the unique housing environment. Key architects for Kyiv’s development began publishing proposals to focus more on investing in public infrastructure to better the lives of people. In 1977, Architect Joseph Karakis sought to humanize the monotony of khrushchevka life; however, these idealistic proposals were deemed too ambitious and denied (Dobrova 2017, 36).

The problem of monotony was ultimately never solved. What was once seen as a massive success for the housing crisis is now a crumbling urban jungle, as it was only a matter of time before the khrushchevka in Kyiv would become obsolete. Human geographers Michael Gentile and Örjan Sjöberg comment on the longevity of khrushchevka, writing that initial building designs, techniques, and materials were all of poor quality to make way for rapid industrialization. It is only post-1975 that apartments improved in both spaciousness and better standardized principles. This meant that, by the 1980s, the first generation of khrushchevka were already beginning to decay. This was the inception of the now common pejorative use of the neologism “khrushchoby” (a portmanteau of khrushchevka and the Russian word for ‘slum’, trushchoby), due to their slum-like appearance (Gentile and Sjöberg 2006, 704).

While the center of the city has been somewhat cleaned up, residential districts on the outskirts of Kyiv are home to endless rows of outdated khrushchevka. The Pozniaky District on the left bank of Kyiv was primarily constructed from concrete panels, which have since crumbled and are in desperate need of repair (Zupagrafika 79). The crude structures which remain were either left abandoned by their owners, or are inhabited by people who refuse to leave the land, claiming that newer high rises provide even more cramped conditions. Some tenants in Pozniaky have refused to leave the land and set up shack-style housing instead.

Governments in other Soviet cities such as Moscow reported derelict conditions as early as the late 1980s. It was deemed not technically possible to reconstruct these buildings, as their foundation was already of extremely poor quality, so government officials called for their demolition instead (Moscow Department of Urban Development Policy 2017). Although old apartments are gradually being removed in various parts of the former Soviet Union, including Moscow, the Kyivan government is struggling to demolish buildings due to a need to relocate residents to newer high rises (Erofeev 2014). The government does not have the budget to afford expensive city planning, and replacing all khrushchevka with high-rises could create an unsightly concrete mess with poor livability. According to government data, many buildings in Kyiv are unsuitable for living and have been condemned, with 3,055 khrushchevka (housing 200,000 families) needing to be demolished (Akage 2021).

Bibliography

Akage, Anna. “How to Renovate Kyiv: Start by Replacing All Soviet-Era Slums.” Worldcrunch, Worldcrunch, 20 Aug. 2021.

Ерофеев, Николай. “История хрущевки,” Открытая левая. 24 декабря 2014. http://openleft.ru/?p=4962 [Erofeev, Nikolay. “The History of Khrushchevky,” Open Left. December 24th, 2014.]

Choate, Ksenia, “From “Stalinkas” to “Khrushchevkas”: The Transition to Minimalism in Urban Residential Interiors in the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964″. PhD diss. Utah State University, 2010.

Dobrova, Anna. The role of trust in participatory process : a contextual study of mass housing district in Kyiv [Diploma Thesis, Technische Universität Wien]. reposiTUm, 2017.

Gentile, Michael, and Örjan Sjöberg. “Intra-Urban Landscapes of Priority: The Soviet Legacy.” Europe-Asia Studies, vol. 58, no. 5, [Taylor & Francis, Ltd., University of Glasgow], 2006, pp. 701–29.

Gunko, Maria, et al. “Path-Dependent Development of Mass Housing in Moscow, Russia.” Housing Estates in Europe, 2018, pp. 289–311.

Koveshnikova, Alexandra. “Genesis of creativity of the Ukrainian architect Anatoly Vladimirovich Dobrovolsky.” Academic Bulletin Ural NII proekt RAASN. No.1. 2014. pp. 59-62.

Meuser, Philipp and Zadorin, Dimitrij. “Ten Parameters for a Typology of Mass Housing.” Towards a Typology of Soviet Mass Housing: Prefabrication in the USSR 1955 – 1991, DOM publishers, Berlin. 2016.

Moscow Department of Urban Development Policy. Kompleks gradostroitelnoy politiki [Housing policy roadmap]. Moscow Government, 2017. https://stroi.mos.ru/snos-piatietazhiek

Poddubnaya, Daryna, and Anna Shaidiuk. “Kyiv’s Tsarist and Stalinist Buildings.” Vestor.estate, 6 May 2021, https://vestor.estate/kyiv-tsarist-and-stalinist-buildings.

Tugarinova, Sofiya D. “Seven Sisters Ensemble: High-rise Construction Project Development in Moscow in the 1940s-1950s.” Moscow State Academic Art Institution named after V.I. Surikov, Department of Theory and History of Art. Foundation privee Maison Burganov Vol. 3, 2016. pp. 25-42.

Veryovki, Alexander, et al. “Kyiv.” Eastern Blocks: Concrete Landscapes of the Former Eastern Bloc. Zupagrafika, 2019. pp. 78-100.

One Reply to “Kyiv: Squatter Cities & Megacities”

Comments are closed.