Questions: How has colonialism affected Kyiv’s population? How has Kyiv’s linguistic identity changed over time? What different eras of colonialism occurred in the city, and how did they differ? What is Kyiv’s colonial legacy?

Thomas Bates relates Antonio Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony to tsarist Russian rule, writing that social order – no matter how exploitative – is necessary to make hegemony function. This is done on the basis of establishing a “superiority” of culture, and a new culture which “proves its historical superiority only when it replaces the old.” (Bates 1975, 365-366). Cultural hegemony is a major aspect of the colonial exploitation of Kyiv, ever since the Kyivan Rus was occupied by the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1472 (Hamm 1995, xi). Stephen Velychenko, a Ukrainian studies professor, specifically argues that Russification was the condition that allowed Russian rule in Ukraine to be considered colonialism, despite the restrictive definition of the concept by western literature. Russification is a form of assimilation that glorified the image of Russia and declared Ukrainian people to be uncivilized, uneducated, and uncultured. Kyiv is a prime example of this process due to its position as an administrative capital during both the Russian Empire and Soviet Union. 19th century laws under tsarist Russia abolished Ukrainian laws and institutions in the city, meaning that adopting the Russian language inherently meant that Russian identity would be adopted as well (Velychenko 2009, 453).

In the tsarist era before 1923 and in the Soviet era post-1937, ignorance of the Russian language resulted in low-paying jobs and low social status, despite an absence of subjugation based on race and other visible traits as was par for the course in western European nations (Velychenko 2009, 455). In fact, Ukrainian communists developed the term “colony of the European type” in the 1920s, which is the perspective that shall be used here to study Kyiv’s evolving colonial identity throughout the 20th century. Kyiv in the 19-20th century would see shifts from Russophone assimilation in being part of “Little Russia” (a pejorative/ diminutive term for Ukraine), to complete cultural annihilation as an extraction colony for Germany and the Stalin-era USSR. This would ultimately lead to a post-colonial movement focused on revitalizing the Ukrainian language and culture.

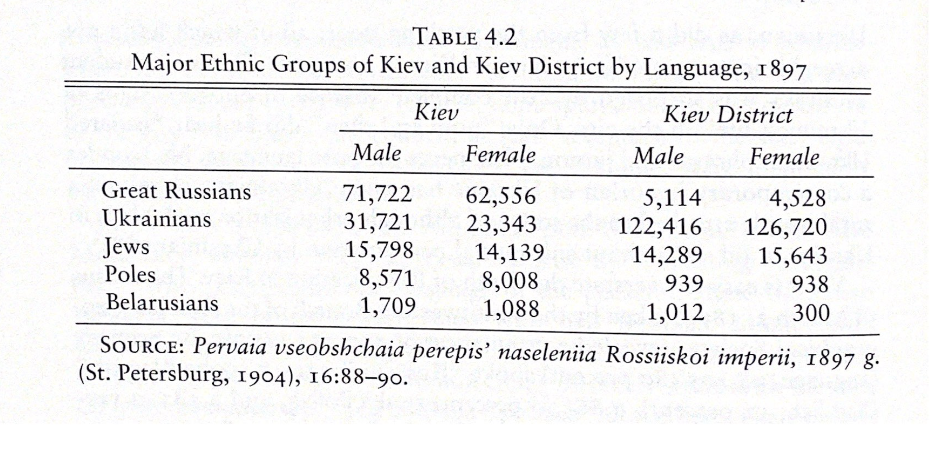

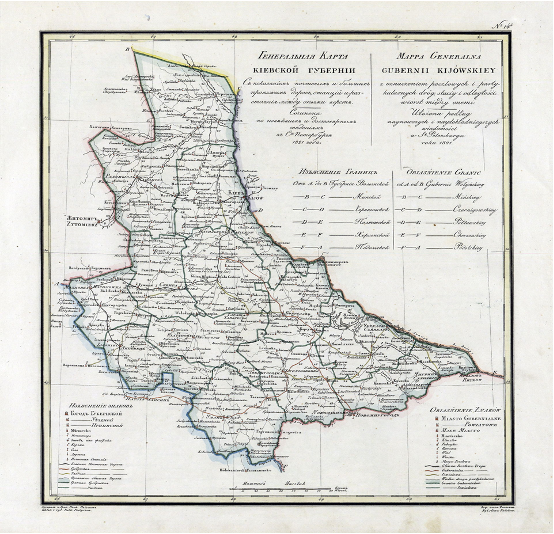

Following the signing of the Pereyaslav Agreement, in which the Zaporozhian Cossacks signed over allegiance to the Russian monarch, Kyiv became an administrative division within the Russian Empire from 1800 to 1925. Russia decided to follow in the footsteps of other colonial policies during 19th-century European imperialism by breaking its Ukrainian colony into a series of governorates (губерніі) ruled by Russian governors. Kyiv became one of the most influential of these governorates by having the biggest population in the empire, 3,559,229 people, despite remaining mostly Polish and Ukrainian in culture (Hamm 1995, 87-88). This included both “Kyiv” as a capital city, as well as the countryside on the outskirts. The legacy of the Kyiv governorate has persisted into the modern day, with the city now contained within the Kyiv Oblast’ (province).

Kyiv’s large population pushed the Russian empire to use political and economic means to suppress non-Russian language and culture influences to “modernize” the governorate and assimilate it with the rest of the empire. Michael Hamm argues that Russification was mostly conducted through commerce, as Russian merchants exercised great economic influence over the city and Russian became the primary language of trade (Hamm 1995, 94). Some literature presents this as a natural outcome of Ukraine’s geopolitical location and development of transport and trade, which initially allowed the Kyivan Rus to garner such a wide territory. This theory suggests that a change to speaking in Russian was merely a decision by Ukrainian merchants. However, historian Oleksiy Sokyrko argues that Russian rule over the nation starting in the 1780s used coercive legal means to prohibit. Cossack officers of the native Ukrainian hetman government from participating in trade altogether. Strict government regulations ensured that Petersburg had sole control over commerce, imposed taxes on it, and business was Russified. The edict on “Privileges Extended to the Merchants of the City of Kyiv” signed by Tsar Nicholas I in 1834 encouraged ethnically Russian merchants and manufacturers to move to Kyiv, thus making “Greater Russian” commerce overrepresented over native “Little Russians” and pushing out competition (Sokyrko 2011).

Historians Andrii Danylenko and Halyna Naienko further disagree with scholarship which labels Russification as a natural progression by stating how prohibitive management in Ukraine under the Russian Empire was very much a purposeful effort. Initially, Ukraine and its language was referred to as “Little Russian” due to it being seen as merely a vernacular form of Russian. However, as prominent writers and ethnographers writing in Ukrainian began to emerge in the late 19th century, the “Little Russian” people of the regime capital, Kyiv, were perceived as a threat to tsarist authorities. On July 18th, 1863, Russia’s Minister of Internal Affairs banned the publication of books in Ukrainian, and further prohibitive and punitive measures followed in the 1870s (Danylenko and Naienko 2019, 34-35). Authorities aimed to remove the Ukrainian language from common use since it disrupted nation-building efforts in Kyiv. Danylenko and Naienko document that, between 1876 and 1917, over 400 legal documents existed to ban the use of Ukrainian in education, literature, science, theater, church, and other fields (Danylenko and Naienko 2019, 36).

After the dissolution of the Russian Empire following the Bolshevik Revolution, new Soviet authorities allowed for the brief establishment of an independent Ukrainian republic separate from the Communist Party. However, merely four years later, the nation was once again merged with Russia as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Hamm 1995, 235). Due to Kyiv’s influence during the tsarist regime, the local population was highly anti-revolution, so Kyiv’s Bolshevik group disassembled and the capital of the Socialist Republic moved from Kyiv to Kharkiv in 1934, making Kyiv lose its image as a “Greater Russian” city in the process (Hamm 1995, 234). Moreover, the Bolshevik conquest of Kyiv had Russian troops shooting anyone who spoke Ukrainian or considered themself a Ukrainian as a means of “liberating the Ukrainian proletariat” (von Hagen 2015, 161). Bolsheviks destroyed Ukrainian texts and killed anyone who showed sympathy to traditional Ukrainian culture, such as those wearing embroidered ‘vyshyvanka‘ shirts. Such ferocious behavior agitated the Kyivan people and destroyed their faith in “Greater Russian” authority (von Hagen 2015, 162).

Kyiv was less industrially developed than Kharkiv and was overall viewed as a socially “unreliable” city. It was remarked that Kyiv was inhabited by “more than a half a million [representatives of the] middle and petty bourgeoisie and unqualified laborers, while the proletarian stratum will be absent” (Yekelchyk 1998, 1230). This diverse social composition of the city worried party officials, who much preferred the security of Kharkiv, an industrial city with a majority working-class population.

The 1930s in Kyiv were mostly marked by the totalitarian regime of Joseph Stalin.

Historian Serhy Yekelchyk conducts an analysis of Stalin’s initial policies in Kyiv aiming to turn the city into a “proletariat capital,” despite Kyiv’s initial alleged lack of “proletariat appeal”. Stalin was motivated to move the capital back from Kharkiv primarily because Kyiv was the geographical center of the Ukrainian territory, making it easier for Soviet authorities to oversee the population. The change of the capital was also a political statement, with the act of the transfer itself intending to demonstrate the totalitarian political and military might of the Soviets (Yekelchyk 1998, 1229). In the pursuit of making Kyiv a “model Soviet city,” Kyiv was cleared of “criminal and politically unreliable elements”, resulting in over 20,000 individuals being purged from the city and sent to concentration camps (Yekelchyk 1998, 1235). Authorities under Stalin significantly invested in industrializing the city and disciplining, or otherwise purging, the elements they did not like. This was all undertaken with a tone of “gradual silent Russification,” where the only way Stalin could hope to reshape the republic was to slowly abolish Ukrainian language and culture (Yekelchyk 1998, 1241).

However, over time these policies grew from silent to oppressive, as Stalin never quite achieved the model Soviet city he hoped for. Taras Kuzio, an expert on Ukrainian politics and security, writes that while ethnic Russians and Russian speakers were viewed as compatriots and the “elder brother of the USSR” by Soviet leaders, ethnic Ukrainians continued to be seen as a possible source of counter-revolutionary action and thus untrustworthy (Kuzio 2017, 290). Kyiv accounted for a large territory, but the people had a distinct lack of zeal for the Soviet regime. A starvation-based genocide called the Holodomor was imposed on Kyiv and other Ukrainian cities, with Stalin informing Soviet leaders that he would ideally deport the Ukrainian people but “there were too many of them and there was no place to which to deport them” (Kuzio 2017, 291).

The exploitation of Kyivan people extended into the 1940s. After the Soviet Union’s loss of the first Battle of Kyiv in 1941, Kyiv was captured on September 19th and briefly placed under German occupation in a period known as Reichskommissariat Ukraine. Unlike previous policies of assimilation, German forces did not care for the residents of Kyiv and made no attempt to extend German cultural influence. Instead, Ukraine was declared the “granary of Europe” and a “breadbasket” for the German Reich, thus merely reduced to an extraction colony and put under the administration of the Nazi Party member Erich Koch (Joesten 1943, 331). Joanchim Joesten, a German-American journalist who once served as a member of Germany’s KPD, writes about Koch’s administration of Kyiv. He describes how Kyiv’s war-torn state was a disappointment for the Nazis who openly planned to use the land as a slave state, despite prior public statements of wanting to liberate Kyivans from Bolshevik rule (Joesten 1943, 333). Nazi forces created a new “model farmer” order and sent Danish and Dutch (racially kindred) farmers to work in Ukraine in place of German farmers, while Kyivan Ostarbeiter, “eastern workers,” were sent to Germany as slave workers (Joesten 1943, 338).

Karel Berkhoff, a historian focusing on holocaust and genocide studies, further emphasizes this point in his chapter “Famine in Kiev” of the book Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule. There, he describes the deliberate starving of Kyiv as a method of depopulating the city. Hitler’s direct command was the policy that “Kyiv must starve,” since it was more economically beneficial for the Germans to control a large territory without the city’s population (Berkhoff 2004, 164-165). Moreover, propaganda was used to inform Kyivans that their low food supply was to be blamed on the previous “incompetent” Soviet regime, as a means of further dismantling Russian power (Berkhoff 2004, 166).

When the Soviet Union regained Kyiv during the second Battle of Kyiv in 1943, the remaining population was suffering from trauma by Stanilist oppression. Kyiv also had a dwarfed population either due to death by malnutrition or being deported to work as laborers in Germany (Priemel 2015, 51). In order to unify the Ukrainian people with the ethnic Russian population, Nikita Khrushchev’s regime focused on gentler assimilation policies following Stalin’s death. Jeremy Smith, a historian focusing on non-Russian states of the former Soviet Union, writes about Khrushchev’s “democratic” education reforms in 1959. Parents of children in Soviet schools were given the option of sending a child to an institution conducted in native Ukrainian or a Russian school (Smith 2017, 983). Russian was also made a compulsory second language in non-Russian republics. These early Bolshevik principles of equity for all Soviet territories ensured that Russian would remain the main common language of the USSR, while Kyiv slowly began to reclaim its native language. This was a complete change in tone compared to the Stalin regime, which wished to reshape Kyiv into a Russified “model city.”

Modern-day Ukraine continues to be fractured along linguistic and ideological lines, with the post-Soviet period in Kyiv focused on a postcolonial reconstruction of the Ukrainian language and traditional culture. Ever since Ukrainian emerged as a literary language, the choice to use Ukrainian has become a political action rather than just a way to express oneself (Rewakowicz 2011, 605). Citizens now proudly wear traditional embroidered shirts called vyshyvanka for which they were once killed. There is a divide between Ukrainian only being used for highbrow academic language, while popular literature and poetry is written in Russian (Rewakowicz 2011, 601). Although still an uphill battle, Kyiv has transformed from a “Russian” city to the capital of an independent Ukrainian state, with Ukrainian being the only language of instruction in schools and documentation, and the name “Kyiv” itself now being globally transliterated from Ukrainian, not Russian.

Bibliography

Bates, Thomas R. “Gramsci and the Theory of Hegemony.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 36, no. 2, 1975, pp. 351–366.

Berkhoff, Karel C. Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004. Print.

Danylenko, A., Naienko, H. “Linguistic russification in Russian Ukraine: languages, imperial models, and policies.” Russ Linguist 43, 19–39 (2019).

Joesten, Joachim. “Hitler’s Fiasco in the Ukraine.” Foreign Affairs, vol. 21, no. 2, Council on Foreign Relations, 1943, pp. 331–39

Kuzio, Taras. “Stalinism and Russian and Ukrainian National Identities.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies, vol. 50, no. 4, University of California Press, 2017, pp. 289–302.

Michael F. Hamm. Kiev: A Portrait, 1800–1917. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1995.

Rewakowicz, Maria G. “Difficult Journey: Literature, Literary Canons, and Identities in Post-Soviet Ukraine.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies, vol. 32/33, [The President and Fellows of Harvard College, Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute], 2011, pp. 599–610.

Smith, Jeremy. “The Battle for Language: Opposition to Khrushchev’s Education Reform in the Soviet Republics, 1958–59.” Slavic Review, vol. 76, no. 4, Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp. 983–1002.

Sokyrko, Oleksiy. “The Demise of Merchants.” The Ukrainian Week, 3 Feb. 2011, https://ukrainianweek.com/History/17557.

Velychenko, Stephen. “Colonialism, Bolsheviks, and Ukraine.” Ab Imperio, vol. 2009, no. 2, 2009, pp. 435–456.

von Hagen, Mark. “Wartime Occupation and Peacetime Alien Rule: ‘Notes and Materials’ toward a(n) (Anti-) (Post-) Colonial History of Ukraine.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies, vol. 34, no. 1/4, [The President and Fellows of Harvard College, Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute], 2015, pp. 153–94.

Yekelchyk, Serhy. “The Making of a ‘Proletarian Capital’: Patterns of Stalinist Social Policy in Kiev in the Mid-1930s.” Europe-Asia Studies, vol. 50, no. 7, [Taylor & Francis, Ltd., University of Glasgow], 1998, pp. 1229–44.