QUESTIONS: How have Jakarta’s colonial past and its social hierarchies been reflected in built form? How have colonial legacies persisted in an urban Jakarta post-independence?

Dividing and conquering space

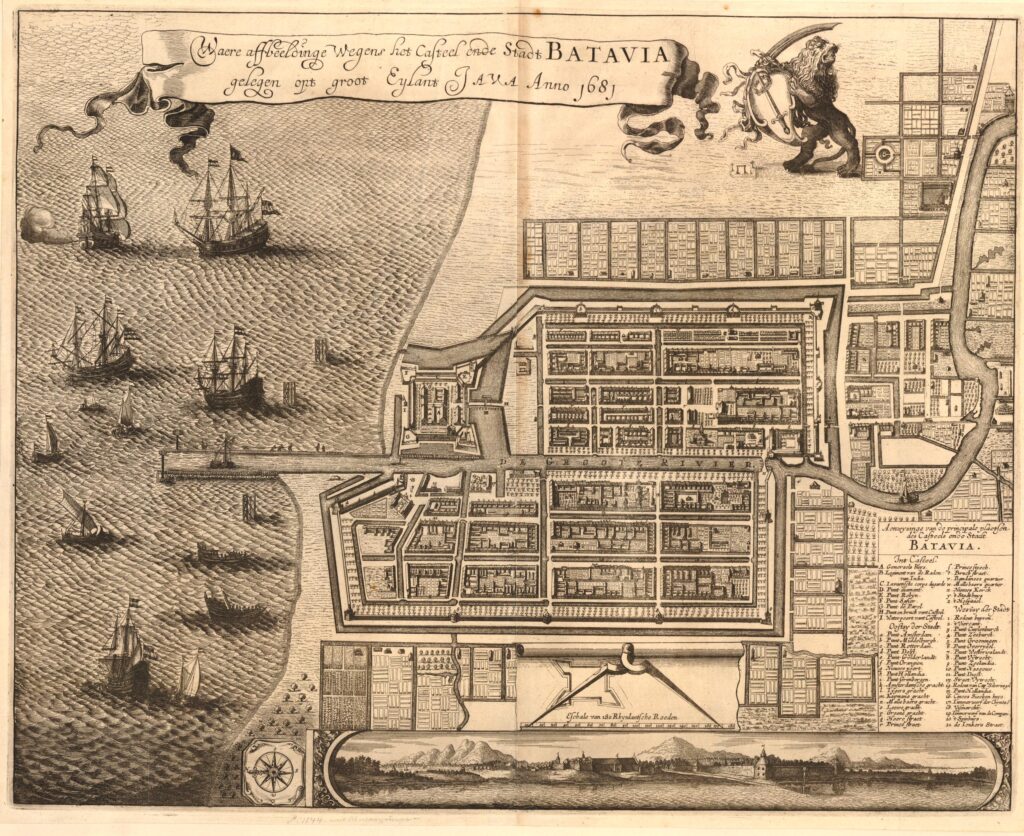

When the Dutch East India Company (VOC) established its presence in Batavia in the early 1600s, the city planners aimed to replicate Dutch architecture and spatial planning by including canals and a grid plan (Kehoe 2015, 4-7). Although the Dutch elements of Batavia provided a sense of familiarity and comfort to its Dutch inhabitants, the distinct, non-indigenous urban designs also reinforced colonial power and control over Batavia (6).

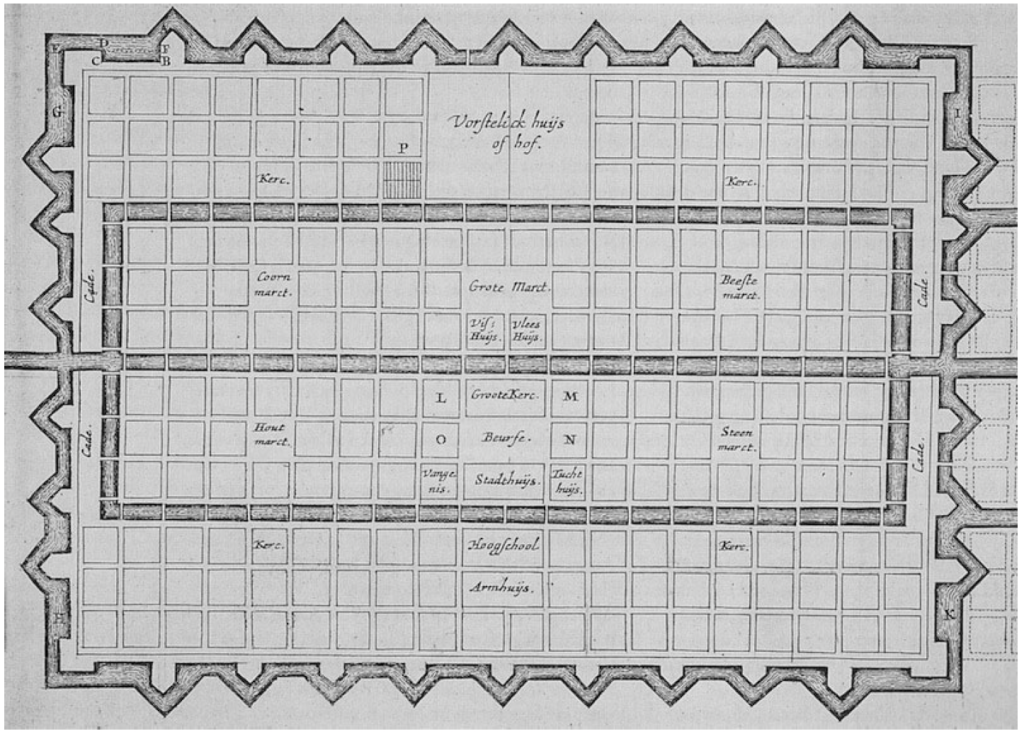

Batavia’s expansion during the seventeenth century aligned with broader Dutch experiments with urban planning. In particular, Batavia’s urban plan showed some resemblance to Simon Stevin’s “Ideal Plan for a City” (see Figures 1 and 2) in 1650. In Stevin’s plan, the entirety of the city is in a uniform, rectangular grid layout with a body of water that cuts through the center of the settlement. Important functional buildings such as government, school, and church buildings were located along the same axis (Weebers and Ahmad 2014, 549-550).

In the case of Batavia, elements found in Stevin’s plan, such as canals and walls, became elements that intentionally emphasized otherness and social hierarchy in Batavian society. Batavia’s walled colonial city separated the Dutch and elite populations from other residents who lived in surrounding kampungs, settlements that were divided by ethnic groups at the time (Kehoe 2015, 16). Canals, a symbol of Dutch cities at the time, served as physical barriers to direct and limit human movement in specific spaces. By not building multiple bridges and entrances into the walled colonial city, the Dutch were able to restrict access of the unwanted outsiders, such as the local Chinese and enslaved populations (12). Consequently, Kehoe argues that while a grid plan like Stevin’s “Ideal Plan for a City” may convey a sense of equality between city blocks, Batavia’s implementation of a grid city resulted in the reinforcement of rigid social divisions and restricted interaction between various ethnic groups (11). Social divisions were imposed indirectly through physical space in order to maintain a hierarchy between Batavian residents; wealthier, European residents reside in areas that are well connected compared to poorer residents that live in neighborhoods that are less accessible to wealthier areas.

Transcending and transgressing spaces

Interestingly, Kehoe highlights the Chinese merchant population as a demographic that was able to briefly transcend social divisions and occupy spaces that local Javanese cannot. At that time, several wealthy Chinese merchants were afforded the same privileges as Dutch Batavians, walking with a servant and residing within the walled colonial city (Kehoe 2015, 16). As Chinese immigration continued to swell in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Chinese made up 20 percent of the total population in Batavia in the 1730s (Blussé 1981, 169). By 1739, there were 4,000 Chinese residents living within Batavia and 10,000 in the neighboring areas (Knörr 2009, 73).

As some wealthier Chinese began operating sugar plantations in the Ommelanden, the areas surrounding Batavia, more Chinese moved inland to work under them (Knörr 2009, 73). The sugar boom during the early 1700s made the Chinese-dominated sugar industry very prosperous, leading to an influx of new Chinese immigrants and growing anti-Chinese sentiment among the Dutch. Anti-Chinese sentiment climaxed with the Chinese Massacre of 1740 after a battle broke out between the Dutch and Chinese sugar laborers over rumors about using drowning as a Dutch solution to the “Chinese problem.” Blussé estimates that approximately 10,000 Chinese residents died in the massacre (Blusse 1981, 177). Kemasang estimates only approximately 3,000 Chinese residents, less than half of the Chinese population pre-massacre, survived the violence (Kemasang 1982, 68).

Anti-Chinese sentiment continued under the Dutch rule although they were not as well documented in the nineteenth century. During the Indonesian independence movement in the 1940s, local Chinese were targeted as enemies because they were seen as the Dutch’s ally (Knörr 2009, 73). In the late 1960s, Chinese Indonesians were legally discriminated against by Suharto’s New Order regime with attempts to erase culture through the closure of Chinese schools and bans on Chinese media and political participation (Knörr 2009, 74). Many Chinese Indonesians opted to change their surnames to be more Indonesian-sounding to avoid discrimination (Knörr 2009, 74). The use of Mandarin Chinese and practice of Chinese culture remained illegal until 2000 when it was overturned as part of Indonesia’s Reformasi or the Reform Era after the end of Suharto’s rule (Knörr 2009, 81).

The height of anti-Chinese sentiment during Suharto’s rule was the May 1998 riots, a period of civil unrest due to economic instability. While the movement was initially spurred by calls for democratization, rioters destroyed property owned by Chinese Indonesians and committed physical and sexual violence against the them (Kusno 2003, 150). Most notably, Glodok Plaza, an electronics shopping center in Jakarta’s Chinatown, was burned down with torches and gasoline bombs (156). Similarly, Pasar Glodok, located at the edge of Jakarta’s Old Town, was rebuilt with a colonial architectural style after it was destroyed in the riots (159). When the buildings were rebuilt, Kusno emphasizes the lack of acknowledgement of the atrocities committed there (159). In both instances, the violent, intercultural conflict in Glodok was replaced with new imaginaries of Glodok’s symbol as Indonesia’s electronics trading hub and as a vibrant part of Jakarta’s colonial period.

Democratizing colonial space and history

While the Dutch VOC aimed to reproduce social barriers to retain power, Indonesians aimed to revisit the colonial era through their own interpretations of Dutch colonialism and Indonesian identity post-independence in 1945. Sastramidjaja cites global trends of nostalgia as a catalyst for a re-focus on Jakarta’s past. Specifically, a proposal to build a road through Kota Tua (Jakarta Old Town) in the 1970s drew widespread attention and protests from the local community to preserve the town’s colonial history and architecture (Sastramidjaja 2014, 451). However, large revitalization projects failed one after the other in the following decades due to ineffective government collaboration and changing Indonesian leadership (452). Even as the government sought to preserve and maintain Jakarta’s colonial architecture through Kota Tua, it refused to acknowledge the Dutch colonial period, referring to the area as “Old Jakarta” or pre-colonial Jayakarta instead of Batavia. The government’s lack of acknowledgement regarding Dutch colonialism illustrates its pursuit of shaping Indonesia’s collective memory but also its goal of economic growth (453-454).

Ultimately, the potential of tourism and increased revenue incentivized the Indonesian government to prioritize Kota Tua’s redevelopment as “a place of tranquility amidst the hectic city, with its historical European ambience” (456). In response, Sastramidjaja critiques the commodification of Kota Tua, which only serves to meet political goals and isolates the physical space from its historical context (448, 455). Rahmayanti et. al. describe the restoration of economic activity through the redevelopment of a colonial building that housed an insurance company during the Dutch colonial era. Despite its restoration as a boutique hotel, the building was only seen as a contributing factor to the “colonial ambiance” (Rahmayanti et al. 2021).

Su et al. go further and critique the reduction of heritage and history to a single monetary value set by economic relationships and not by the “use value” of cultural legacies and memories (Su et al. 2018, 34). Without adequate consideration and thought, Kota Tua’s participation in the “heritage industry” risks the sanitization of Indonesian history into neatly consumable narratives (Sastramidjaja 2014, 465). Su et al. describes the points of tension between urban heritage producers and tourist consumers (Su et al. 2018, 33). Urban heritage producers, generally the ruling political group, “seek to present heritage resources in cities in ways that help them to maintain their legitimacy and authority” (Su et al. 2018, 34) However, the presented narratives on heritage may not align with tourists’ expectations.

In a 2014 revitalization study by the OMA architectural firm, the firm proposed possible futures for the historic Tjipta Niaga building in Kota Tua, by combining the government’s objectives of expanding its tourism industry along with highlighting community building and growth (“Kota Tua”). OMA refrained from using the “freeze and conceal” approach, where historic buildings are “frozen” in the past, do not interact with present-day city landscapes, and only serve as a tourist attraction. Instead, OMA’s “engage and reveal” strategy proposed small scale changes such as subdividing large spaces to maximize tenant space and revenue in addition to allocating the spaces for mixed use. By combining office, commercial, and public-use spaces, OMA believes that Tjipta Niaga would serve as both a historic site and also a cultural hub stemming from organic interactions within the community (“Kota Tua”).

Although capitalism plays a significant role in the revitalization of colonial spaces, it would be negligent to dismiss grassroots movements that seek to re-engage with Jakarta’s colonial history in the twenty-first century. The combination of ersatz nostalgia – a secondhand nostalgia – and tempo doeloe – a nostalgia for the Dutch colonial era in the East Indies – created a new generation of youth interested in reclaiming their Indonesian heritage through interacting with Jakarta’s Dutch colonial history (Sastramidjaja 2014, 447). By offering walking heritage tours of Kota Tua, Indonesian youth re-interpret and democratize Jakarta’s history. In particular, they engage participants in the histories of marginalized groups through firsthand accounts of Chinese Indonesians living in Kota Tua, incorporating Chinese histories back into the broader history of Indonesia and the Indonesian identity (464). In direct contrast with the government’s omission of Dutch history and influence on Jakarta, the youth heritage trails were not subjected to government censorship of historical narratives and offered an alternative approach to interacting with history through active experience instead of passive consumption.

Bibliography

Blussé, Leonard. “Batavia, 1619-1740: The Rise and Fall of a Chinese Colonial Town.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 12.1 (1981): 159-178.

Kehoe, Marsely L. “Dutch Batavia: Exposing the Hierarchy of the Dutch Colonial City.” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 7 (2015) 1-29. DOI:10.5092/jhna.2015.7.1.3.

Kemasang, A.R.T. “The 1740 massacre of Chinese in JAva: Curtain raiser for the Dutch plantation economy.” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 14.1 (1982): 61-71. DOI: 10.1080/14672715.1982.10412638.

Knörr, Jacqueline. “‘Free the dragon’ versus ‘Becoming Betawi’: Chinese identity in contemporary Jakarta.” Asian Ethnicity 10.1 (2009) 71-90.

“Kota Tua.” OMA. Accessed November 2, 2021. https://www.oma.com/projects/kota-tua.

Kusno, Abidin. “Remembering/Forgetting the May Riots: Architecture, Violence, and the Making of “Chinese Cultures” in Post-1998 Jakarta.” Public Culture 15.1 (2003) 149-177.

Rahmayanti, K., I. Rachmayanti and A A A Wulandari. “Revitalization of Kerta Niaga Kota Tua building in Jakarta as a boutique hotel.” IPO Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 729 (2021).

Sastramidjaja, Yatun. “This is Not a Trivialization of the Past: Youthful Re-Mediations of Colonial Memory in Jakarta.” Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 170 (2014): 443-472. DOI: 10.1163/22134379-17004002.

Su, Rui, Bill Branwell, Peter A. Whalley. “Cultural political economy and urban heritage tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 68 (2018): 30-40.

Weebers, Robert C. M. and Yahaya Ahmad. “Interpretation of Simon Stevin’s ideas on the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (United East Indies Company) settlement of Malacca.” Planning Perspectives 29.4 (2014): 543-555.