Questions:

“When was a sewer system built in your city, and what was the context?”

How is the history of Helsinki’s wastewater management told?

The history of wastewater management in Helsinki can be told through the city’s change in water protection policies. Based on seven sources, I have identified different modes of historical examination: the technological change via waste disposal systems, paradigm shifts, legal history, and river history. The 1850s is the earliest time period my sources cover, while 2015 is the latest.

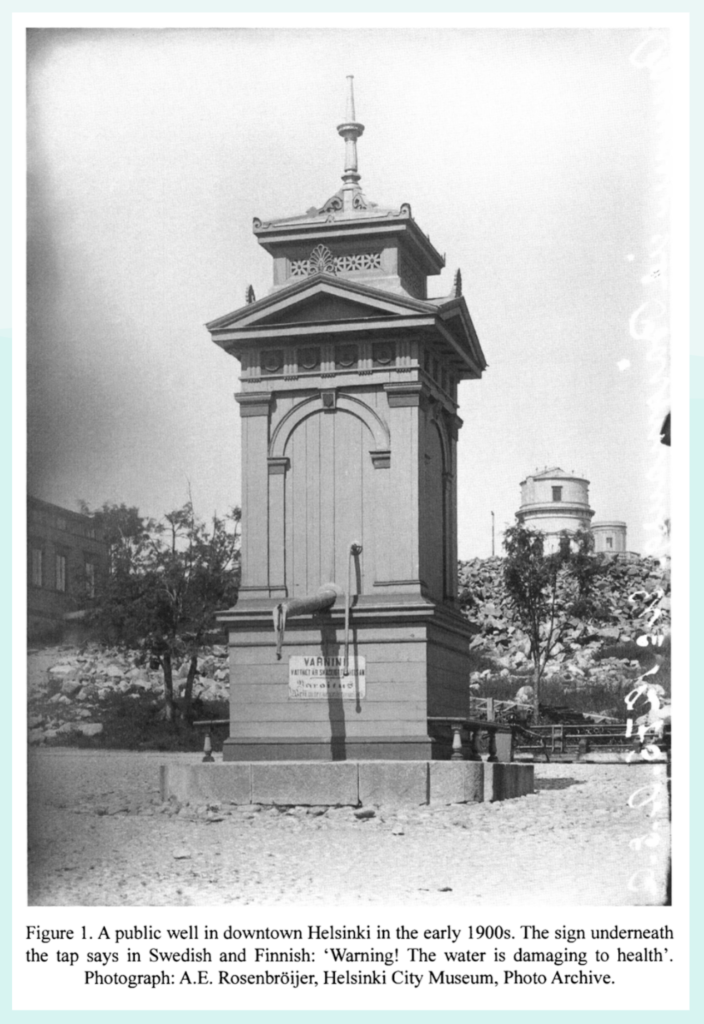

To preface my discussion about how these four modes emphasize different characteristics of Helsinki’s history of wastewater management, Laakkonen with a general summary. In the 1850s, before industrialization, Helsinki possessed more of a “rural” quality than an “urban” one (Laakkonen 2007, 214). Inhabitants relied on public and private wells that often suffered from deadly bouts of contamination due to mishandled waste and other sources of waterborne diseases. During this time, Helsinki dwellers managed their own waste via the “bucket system” (Laakkoken 2001). Essentially, households were responsible for collecting their own solid waste with buckets and delivering them to a dunghill or to the countryside to be used as fertilizer. In 1878, even after the first sewer system was built, the bucket system prevailed because the new sewer system was intended for wastewater only, not solid waste. By the 1870s, almost all of Helsinki was linked by water and sewage networks (Laakkonen 2007, 214). Research that first began at the Helsinki water works, however, quickly led to the outlaw of the use of lead pipes in Helsinki, with the exception of “joints and other fittings” (Katko 2000, 31).

Eventually, however, the upper-class Helsinki residents began demanding “water closets,” or flush toilets, to be installed. They argued for them in the name of hygiene, believing the sea had a “self-purification capacity.” Due to political debates amongst city authorities, the water closet system was not implemented until 30 years later (Laakkoken 2007, 214). In the late 19th century, it was said that “no major pollution problems existed in the urban sea area” (Laakkonen 2007, 214-5). At the turn of the century though, the volume of human waste multiplied alongside population growth. Many scientific studies were conducted in the field of bacteriology and water quality which deemed the construction of two biological treatment plants in Helsinki in 1910 and 1915 necessary (Laakkoken 2007, 215). In 1928, researchers also pushed for six activated sludge plants and one mechanical treatment plant to be built in order to process all wastewater (Laakkoken 2007). In the 1930s, the first two activated sludge plants were created, but the rest were postponed due to WWII (Laakkoken 2007, 215). Two decades would pass before the construction of the new activated sludge plants would continue. By the early 1970s, despite the fact that all of Helsinki’s wastewater was being treated, the sea, bay, and downtown area were already heavily polluted due to wartime neglect and a high population. According to Laakkoken and Laurila, “the state of the sea area of Helsinki was the worst in the 1970s.” This led to the demand for more scientific research centered on removing “limiting nutrients,” such as phosphorus and nitrogen, in the sea area. By the 1980s, the removal of phosphorus from wastewater was gradually showing promising results. However, the discussion concerning nitrogen removal, inside and outside the scientific community, was complicated and led to ambivalence. Eventually, in 1995, the Water Rights Court mandated that the City of Helsinki remove 50% of nitrogen by 1997 and 65% by 2000. These expedited efforts to remove nitrogen, fortunately, yielded positive results that erased Helsinki from the intergovernmental Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission’s“hot spot” polluters list in 2004 (Laakkoken 2007, 216).

If Helsinki’s history of water protection policy is told with a focus on the change in systems, technological innovation is emphasized. While this form of history is logical, it runs the risk of falling into two assumptions: one, it was only a matter of time before Helsinki’s water protection policy would have improved; two, the influx and development of (local and international) waste disposal systems and knowledge related to water, bacteria, and health would naturally lead to increasingly conscientious management of waste and water resources. These assumptions make it is easy to overlook the important shift in mindset that occurred alongside the introduction of the water closet at the beginning of the 20th century. The transition from the bucket system to this new system required three decades. This event signaled the move from an “active and preventative” water protection policy to a “reactive” water protection policy (Laakkoken 2007, 214-5). Laakkoken argues that institutional delay, cycles of policy changes, and paradigm shifts are all interrelated. This is because “new concepts and ideas have had to compete with previous, more established ones and with other new emerging ideas, and still only a few of the proposed concepts are accepted by the scientific, technical, and/or political community” (Laakkoken 2007, 2017-8). Historians Katko and Nygard emphasize that the same kinds of discussions about water services and waste management have been going on for a century. What is different is merely the change in paradigm; the “main focus has changed from public health to the environment.” Now city administration members are not the only ones with “the power of formulating strategies” to “heavily influence technical selections,” but “ordinary citizen[s]” and different groups of new professionals in Helsinki are agents as well (Katko and Nygard 2000, 50). Without including the development of Helsinki’s water protection policies through paradigm shifts, the changes in mindset amongst citizens and professionals become less clear.

On the other hand, Katko et al. examine significant policies and decisions concerning Helsinki’s wastewater management from the 1860s to 2003 through legal history. While the first part of their two-phase study selects 40 “key decisions, the second part ranks them by 13 senior national experts. They hope to locate these key decisions within the larger trends of water and sewage services in Finland (Katko et al. 2006, 390). The Water Act of 1962, for instance, articulated the modern concept of water pollution control in Finland. As mentioned previously, the majority of people in the 1950s believed in the “self-purification of water bodies.” With the passing of this new law, however, community members and industry personnel were required to apply for permits if they wished to release their wastewaters. These permits became “stricter” as the years went by. Then, in the 1960s and 1970s, wastewater treatment plants were quickly constructed to treat water by chemical and biological means (2006, 394). In addition to providing the historical context for the beginnings of modern water systems, they identify which Finnish cities and towns took the lead in enacting certain improvements. In 1876, Helsinki possessed the first urban water system within Finland (2006, 392). Throughout their article, Katko et al. use charts, timelines, and graphs to translate the significance of various legislation. They conclude that legislation surrounding sanitation and water pollution was more important than legislation related to the water supply (2006, 398). Their work not only helps organize Helsinki’s history of wastewater management by focusing on key legislation, but also elaborates how past legislation has caused negative or positive “path dependencies” that impact “future options.”

Without river history, the larger history of Helsinki’s waste management would be misunderstood. Schonach traces the environmental history of River Vantaa and its relationship to its surrounding regions. In her article, the “natural” and “urban” worlds are seen together within the same frame as they should be. Although River Vantaa is considered to be on the “outskirts of the city […] from a city centre perspective,” it has been called “the life stream of Helsinki,” (Schonach 2021, 205). Schonach relates how the river was used at the time and why it was no longer thought of as a potential water supply in the minds of local people, the Helsinki Water Works, and national policymakers. She also insightfully reveals how the neighboring communities did not seamlessly engage with one another due to their respective relationships to the river. Studies that combine the “urban perspective” with “river histories,” however, tend to include the local conflicts between “upstream and downstream communities” in a way that “unites” them. Even though they have different ideas about the river’s value, each of their needs is understood better in the context of their relation to the river (Schonach 2021, 202). Centering River Vantaa in the evolution of Helsinki’s wastewater management draws forth new insights about the history of water and its dependent communities in the past and the present.

Heikkinen and et al. use River Vantaa to discuss the overlooked problem of urban wastewater overflows and how they “challenge our perception of reliable and extensive basic infrastructure, such as sewerage and wastewater treatment” (2016, 1455). They chronologically characterize the evolving, politicized discussion surrounding wastewater overflow by analyzing various broadcasting media material, documentary material, consulting firm reports, and local newspapers. Although wastewater overflow is infrequent, its recurrences in 2004 and 2015 demonstrate that the issue has not been viewed in the “continuum of the river water-quality improvement during the last three decades” (Heikkinen et al. 2016, 1467). They argue that River Vantaa’s change in worth and utility – from the “open sewer-like river of the 1960s” to the “important local recreational haven” of today – should be noted in order to form a “common goal” between wastewater management service stakeholders and community members.

Depending on how the city’s evolving water protection policies are presented, the history of wastewater management in Helsinki can take on a myriad of tones and foci. These seven sources hint at the nuances that arise when history is told with an emphasis on technological change via systems, paradigm shifts, legal history, or river history. While all of these works cover a similar time period, their respective foci, in effect, each tell a different but essential part of Helsinki’s relationship with water and its evolving efforts to protect it.

Sources:

Heikkinen, Milja, Paula Schönach, and Ilmo Massa. “Politicization of Wastewater Overflows: The Case of the Vantaa River, Finland.” Water Policy 18, no. 6 (2016): 1454–72. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2016.011.

Katko, Tapio S, “Long-Term Development of Water and Sewage Services in Finland” (2000) From a Few to All: Long-term Development of Water and Environmental Services in Finland by Petri S. Juuti and Tampio S. Katko (eds.) Tempere University Press, ePublications -Verkkojulkaisut (2004), 17-36.

Katko, Tapio S. and Henry Nygard, “Views on the History of Water, Wastewater and Solid Waste Services,” From a Few to All: Long-term Development of Water and Environmental Services in Finland by Petri S. Juuti and Tampio S. Katko (eds.) Tempere University Press, ePublications -Verkkojulkaisut (2004), 47-54.

Katko, Tapio S, Petri S Juuti, and Pekka E Pietila. “Key Long-Term Strategic Decisions in Water and Sanitation Services Management in Finland, 1860-2003.” Boreal Environment Research 11, no. 5 (2006): 389–400.

Laakkonen, Simo. “The Origins of Water Protection in Helsinki in 1878-1928.” Environmental History, 2001, https://blogs.helsinki.fi/envirohist-en/presentation-4/laakkonen_dissertation/.

Laakkonen, Simo, and Sari Laurila. “Changing Environments or Shifting Paradigms? Strategic Decision Making Toward Water Protection in Helsinki, 1850–2000.” AMBIO, vol. 36, no. 2, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, 2007, pp. 212–19, doi:10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[212:CEOSPS]2.0.CO;2.

Schonach, Paula. “Expanding Sanitary Infrastructure and the Shaping of River History: River Vantaa (Finland) 1876–1982.” Environment and History, vol. 21, no. 2, The White Horse Press, 2015, pp. 201–26, doi:10.3197/096734015X14267043141381.

One Reply to “Helsinki: Waste”

Comments are closed.