Questions:

What has come to define the history of street life and urbanization in Helsinki?

How can Helsinki youth’s perspectives and experiences deepen our understanding of the city’s modernity?

According to the Finnish environmental historian Simo Laakkonen, urban environmental history is dominated by the “narrow viewpoint or limited material reflecting the rationalist approach typical of white, middle-aged, middle-class and educated men” (2011). In contrast, Moll and Kuusi (2019), Laakkonen (2011), Broberg and Sarjala (Vaaranen (2004) uniquely explore the perspectives and experiences of Helsinki children and youth, while Andersson et al. (2017) and Kääriäinen and Niemi (2014) compare the lived Helsinki experience using ethnicity as a lens. Viewing the urban environment of Helsinki over time through the eyes of the historically overlooked will deepen and challenge previous understandings of the city and those who reside within it.

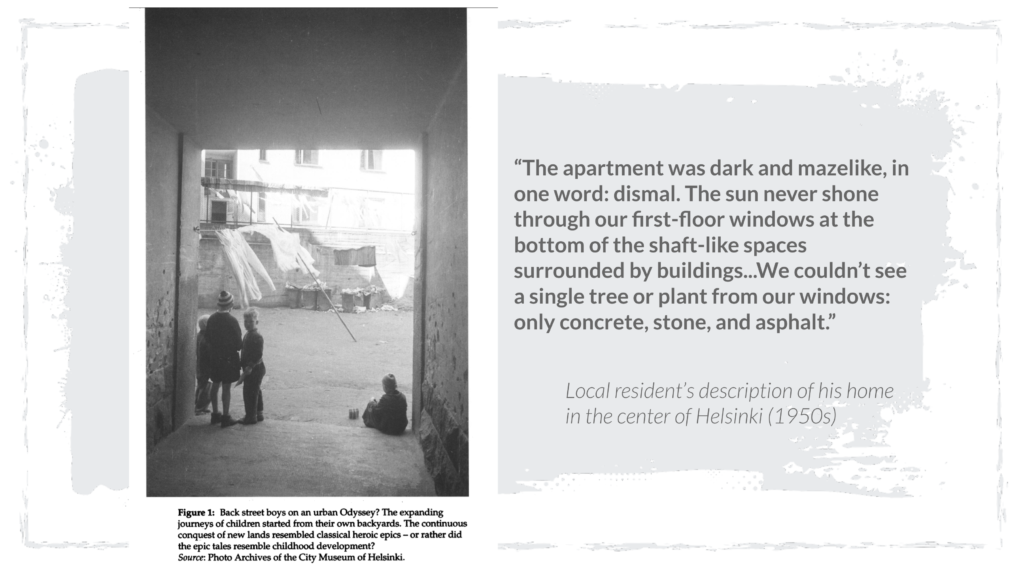

Economic and social historians, Moll and Kuusi focus on the history of urban children’s independent mobility by looking at childhood reminiscences and public material, such as magazines, pamphlets, and documentary films. How much autonomy do children experience in their neighborhoods? How did Helsinki’s rapid urbanization and suburbanization influence Finnish children’s previously “exceptional” autonomy? Moll and Kuusi begin their investigation by prioritizing how various urban planners, parents, and other community members characterized their needs. Especially after WWII, overcrowded housing became increasingly commonplace. The combination of increasing birth rates, migration of local war evacuees, and a series of annexations that stretched the city borders of Helsinki produced this issue. Tuberculosis was a widespread concern, and such living conditions and urban health issues encouraged rigorous health education. As part of the “hygiene movement” of the early 20th century, adults often pushed children outdoors to “get as much fresh air, light and sunshine outdoors as possible” (Moll and Kuusi 2019, 127). Working-class parents’ long working hours also factored into this dynamic.

Not all kinds of outdoor areas, however, were looked upon similarly. Parents became increasingly concerned about their children wandering the same city streets as “vagrants and youth gangs.” They joined “post-war social reformists” to advocate for garden cities and suburbanization so that their families could easily have outdoor green spaces as a part of their lifestyle. The mid-20th century witnessed the multiplication of new suburban homes which were “loosely scattered among the natural formations of the landscape.” Suburban streets that were designed to be “branch-like” with “plenty of space between the buildings, in strong contrast to urban city blocks.” Although there was a continual influx of migrants coming into the city center of Helsinki, its overall population dropped 39 percent, as the population in suburban Helsinki skyrocketed to nearly 66 percent, from 195,000 in 1962 to 324,000 in 1987. In this way, “Finland was urbanized and modernized through becoming suburbanized” (2019, 128). With the increase of new city streets, car ownership, and traffic accidents, it can be argued that suburbanization provided safer, planned green spaces, which preserved the “continuation of children’s independent mobility” (2019, 132).

Distinct from the work of historians, urban researchers’ study of children’s choice of transportation on their school journey within the Helsinki city center provides a distinct angle. Based on 828 schoolchildren’s survey responses, Broberg and Sarjala identify the key elements in Helsinki city center’s urban environment that promote walking or cycling over “active school transport,” such as taking a car or bus. Nearly all the children who lived within one kilometer of their school took a form of “active school transport,” while children who lived more than three kilometers away from school in a relatively remote area tended to walk or cycle (2015, 2-3). Even for children who were a part of a household with multiple cars, the availability of public transportation (or lack thereof) was the most decisive factor behind their choice of transportation (2015, 9). These aspects of their urban environment overshadowed all other identified factors such as the comfort of moving through a forest environment, the density of streetlit intersections, the density of their built environment, age, or gender. In the conclusion, however, the study noted the recommendation of another scholar to explore a child’s “motivational elements on the school journey (a friend’s house, shops, or parks) in the future (2015, 9). By considering children’s perspectives via story or survey results, Moll and Kuusi and Broberg and Sarjala, respectively, uncover important aspects about Helsinki’s urban environment, including the differences between Helsinki’s suburbs and city center.

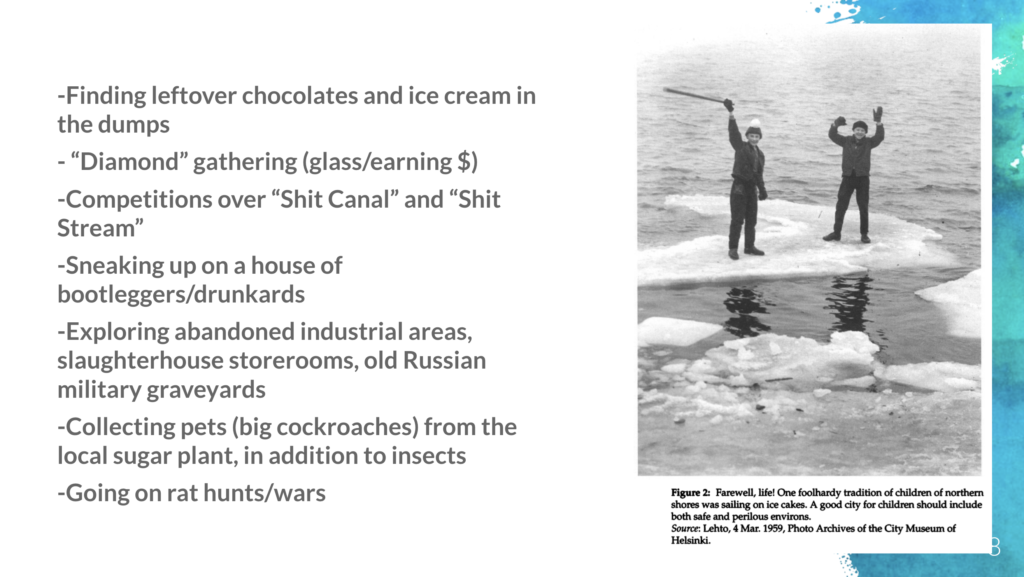

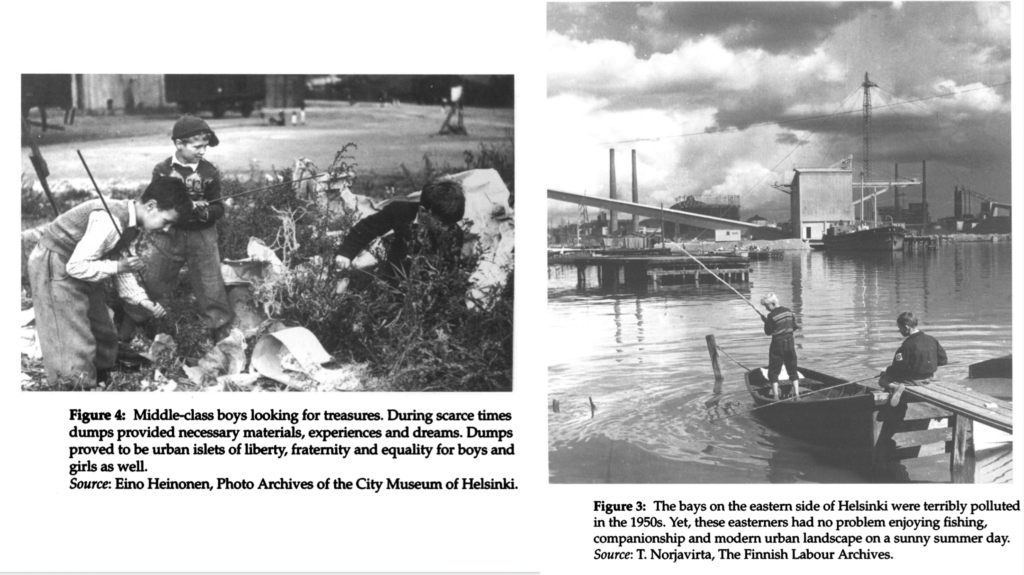

Similarly, by basing his methodology on a collection of childhood reminiscences, Laakonen prioritizes children’s lived experiences over source material that documents how adults perceived children’s worlds to be like at the time. Written reminiscences of Helsinki residents (which are uniquely and widely available to scholars and the public alike) make clear that children were active in almost every outdoor space imaginable. Based on recollections from the 1920s-1950s, Laakkonen builds useful imagery by color-coding children’s movements through different kinds of spaces: Grey correlates with the home environment, yards, courtyards, neighboring streets, and residential buildings; Green and Blue are linked to parks, shores, open spaces, forests, cliffs, water areas, and the ice-covered sea; Black is associated with polluted and prohibited areas; Finally, Brown are spaces with pets, domestic animals, and urban wildlife (2011, 305). The diverse “colors” of children’s play spaces offer a unique prism to Helsinki’s modernization process. Despite the “blandness” that some people attribute to the colors – black and brown – the spaces these two colors represented were far from dull. They provided children with an exciting world in which to experience risky adventures with their playmates (2011, 307). This perspective contrasts the assumption that working-class people’s mundane and impoverished lifestyles automatically defined their children’s experiences likewise. These childhood memories, however, demonstrate that children experienced their changing world in an entirely different way from working-class and upper-class Helsinki adults. Their world was full of exhilaration, discovery, and delight.

After painting an image of the past environment and children’s relationship to it, Laakonen then contrasts these reminiscences of the city from the perspective of “modern” children (note that his article was published in 2011). He observes children’s digital experiences of play within the worlds of “computers and consoles,” which he calls the “the matrix city.” He ultimately argues that children are searching for what children of the past had found in their urban environment: a “dialectical” component in their lives. Children of the past found this sense of balance by moving constantly between the rural and urban, industrial and natural, and adventurous and risky (2011, 322). In a “sanitized modern city” with less and less free grounds to play in, however, Laakonen notes that it is not surprising children should turn to the “updated version of the past grey, green, blue, black, and brown city” (2011, 323). How else can children express themselves and play when their urban environment may not necessarily be evolving to suit their needs? This contrast in children’s memories of play – then and now – provides an opportunity to reflect on Helsinki’s urban history and how its changes impact one generation over another.

Saffle’s book, To the Bomb and Back: Finnish War Children Tell Their World War II Stories (2015), relies on childhood reminiscences for an altogether different purpose – to tell some of the shocking untold experiences of the thousands of Finnish children who were temporarily (and in some cases, permanently) evacuated during WWII. Many of the stories’ introductions, however, speak of Helsinki’s urban environment during industrialization from the child’s point of view. Marita Merilaht’s account confirms Laakonen’s argument about children recognizing contrasting spaces and where to play:

“I was born in Helsinki in 1934. My [family members] and I lived in a modest flat with only two rooms that we heated with wood in a metal woodstove. We had indoor water but no hot water. As children, we had to put the wood my mother brought home in the cellar cabinet, and I remember being frightened to go there alone because a neighbor had died there. But what our apartment lacked, our natural surroundings more than made up for. There was also good terrain for skiing and ice-skating. When I was little, I remember many winter days with -40 Celsius temperatures!” (2015, 175).

This mixture of the natural and urban characterizes Helsinki in the pre-war era. While the stories do not aim to capture how their childhood reminiscences have changed over time, the perspective they offer is nonetheless valuable. The voices of children can act as an insightful guide into the past, since they accessed parts of Helsinki, in ways that their parents or adults may not have experienced.

Alongside historians’ and editors’ efforts to center children in urban environmental history, sociologists have also conducted fieldwork to study the consequences of modernity on youth. In her 2004 ethnography, “The Emotional Experience of Class: Interpreting Working-Class Kids’ Street Racing in Helsinki,” Vaaranen included the voices of eighteen- to twenty-four-year-old Helsinki males. There are at least two kinds of “Helsinki” – “daytime Helsinki” and “nighttime Helsinki.” In the former, young Finnish street racers are bound by their poor educational, social, and employment background. So much so, they experience their “social disempowerment” on an emotional level. Their “struggle needed a stage, and the streets were it” (2004, 100). On the streets, Helsinki youth could finally attain a form of reputation, emotional catharsis, and a sense of freedom through streetcar racing, all of which they lacked in “daytime Helsinki.” They could display their “social capital” in an alternate subuniverse because distinct rules, expectations, pleasures, and allegiances existed in “nighttime Helsinki.” Street racing poses a life-threatening risk on individual racers, yet simultaneously it creates a one-of-a-kind space for their community. Together these Finnish teens can freely move and triumph within “nighttime Helsinki,” unlike in “daytime Helsinki.”

Through participant-observation, Vaaranen argues that “nighttime Helsinki” is one of modernity’s unintended effects on present-day Helsinki youth. She elaborates, it is the realization that upward mobility in “daytime Helsinki” is “desirable” but not attainable that “promote[s] the street-racing crimes of passion, leaving behind death and injury: the human sacrifice of the modern age” (2004, 105). Without these youths’ perspectives, it is easy to privilege “daytime Helsinki” over “nighttime Helsinki when forming an assessment of the city Helsinki. Both of these worlds exist within the same city limits, yet they thrive at contrasting hours of the day and are not equally accessible. Certain city inhabitants cannot witness the other “face” to Helsinki given their status, age, and daily routine; researchers too would be unlikely to experience this subuniverse without “insider” permission. Through her anthropological approach, Vaaranen demonstrates how particular aspects of Helsinki’s urban environment are best seen through the eyes of its city youth.

Unlike Moll and Kuusi, Laakkonen, Broberg and Sarjala, and Vaaranen who champion the positionality and expressions of Helsinki children and youth, Andersson et al. focus on the social dynamic of ethnicity in Helsinki neighborhoods. In their co-authored work, the Scandinavian scholars attempt to measure Helsinki-born residents’ level of tolerance toward ethnic diversity and juxtapose this to those of native-born residents of two other Nordic cities. They hope to “better understand popular imaginations and preferences” (2017, 514). While this housing studies article does not address children, it raises another critical question about perspective. It explicitly asks for negative or positive views of ethnic segregation. While Andersson et al. conclude that further study is needed to determine whether their research can be of any use in policy-making, Kääriäinen and Niemi, on the other hand, release conclusive findings in regards to their study about the relationship between the Finnish police and minority groups in Helsinki. In Finland, ethnic minorities are “strongly concentrated in the Helsinki region” (2014, 6). Considering the lived experiences and viewpoints of ethnic minorities reveal aspects of city life in Helsinki that may not be so apparent to the majority. Kääriäinen and Niemi focus particularly on Russian and Somali minority groups and their distrust of the police. Despite blatant anti-Russian attitudes and forms of discrimination in Finnish society, Russian minorities held an almost equivalent of high trust in the police as native Finns. Somalis being the “so-called visible minority” generally distrusted the police. Both minority groups, however, found that the longer they stayed in Finland, the more they distrusted the police. Kääriäinen and Niemi conclude that this may be the case because of the Finnish police’s dual role in immigration-related issues in Finland. They are often the authority in situations where they “must apply a suspicious approach toward immigrants’ motives in the immigration process.” It is possible that ethnic minorities are at the receiving end of “multifaceted discrimination instead of being a direct result of the kind of police service provided for the minority” (2014, 10). Even though in recent decades, the country has also attracted immigrants from Bosnia, Vietnam, Thailand, Italy, China, Spain, Poland, Hungary, India, Afghanistan, Brazil, Ukraine, Latvia, and Lithuania (Haarmann 2016, 77), life in Finland still reflects a Finn majority. The oscillation between “ethnic boundary-making” and “social integration” continues today in Finnish society, which makes intentional or unintentional policing ever-relevant issues (2016, 75). As Haadmann highlights, “favoring multiculturalism is no longer a national choice but it has become a necessity of crisis management” (2016, 220). In terms of power roles and social standing, being a minority in a multicultural, but nevertheless Finn-dominated society lends to a particular city experience.

In conclusion, this collection of scholarly sources opens up multiple avenues to redefine the history of urbanization, suburbanization, and street life in Helsinki. The past and present experiences of children, youth, and ethnic minorities will only strengthen conceptions of Helsinki’s modernity.

Sources:

Andersson, Roger, Ingar Brattbakk, and Mari Vaattovaara. “Natives’ Opinions on Ethnic Residential Segregation and Neighbourhood Diversity in Helsinki, Oslo and Stockholm.” Housing Studies 32, no. 4 (2017): 491–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2016.1219332.

Broberg, Anna, and Satu Sarjala. “School Travel Mode Choice and the Characteristics of the Urban Built Environment: The Case of Helsinki, Finland.” Transport Policy 37 (2015): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2014.10.011.

Haarmann, Harald. Modern Finland. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2016.

Kääriäinen, Juha, and Jenni Niemi. “Distrust of the Police in a Nordic Welfare State: Victimization, Discrimination, and Trust in the Police by Russian and Somali Minorities in Helsinki.” Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice 12, no. 1 (2014): 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377938.2013.819059.

Laakonen, Simo. “Asphalt Kids and the Matrix City: Reminiscences of Children’s Urban Environmental History.” Urban History 38, no. 2 (2011): 301–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926811000423.

Moll, Veera, and Hanna Kuusi. “From City Streets to Suburban Woodlands: The Urban Planning Debate on Children’s Needs, and Childhood Reminiscences, of 1940s–1970s Helsinki.” Urban History 48, no. 1 (2019): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S096392681900083X.

Saffle, Sue. To the Bomb and Back: Finnish World War II Children Tell Their Stories. New York, Berghahn, 2015.

Vaaranen, Heli. “The Emotional Experience of Class: Interpreting Working-Class Kids’ Street Racing in Helsinki.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 595, no. 1 (2004): 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716204267494.

One Reply to “Helsinki: Anxious Modernity”

Comments are closed.