Introduction

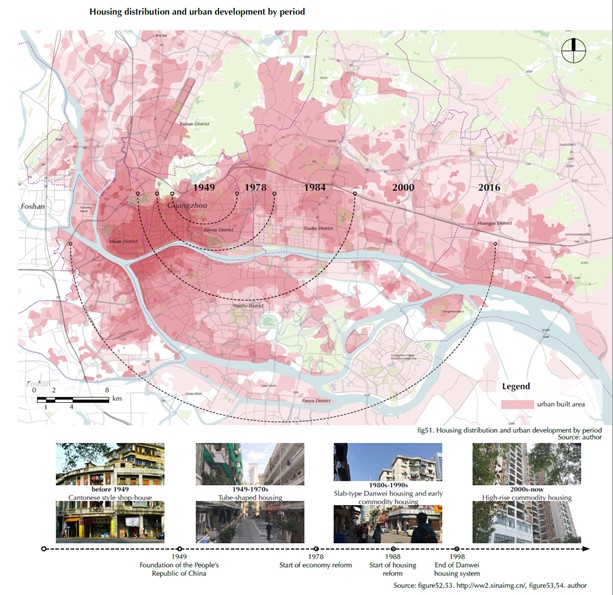

Urban development and urbanization in China can be generally divided into three periods: (1) the feudal and semi-colonial late Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China from 1911-1949; (2) the Communist PRC from 1949-1978; and (3) the reformist PRC after 1978 (Cao 2015, 6-7). As Guangzhou’s pattern of urbanization and development of real estate follows the periodization, the city also developed its unique shape and direction of expansion in response to the different types of existing urban/rural form in the Guangzhou metropolitan area, the existence of dual market created during the reform period, and the different types of interaction between the local state and population. Real estate in this literature review will take the definition of “property in buildings and land” (Merriam-Webster), including historical districts, urban villages, danwei housing, and commodity housing (Huang 2017, 32). Through an examination of existing literature on Guangzhou’s urbanization and real estate development, the literature review seeks to draw the lines of influence and depict the story of how different types of real estate determine the shape of the city.

Periodization of Urbanization

Pre-1949

Historically Guangzhou has been characterized as a port city sitting by the Pearl River on the Southeast coast of China, which, like many other cities, was originally a walled city (cheng) (Yuan 2014, 64). But the extent of the city is not simply contained by the wall. Skinner (1997, 258-261) characterizes Guangzhou and the surrounding suburb area as a “rural-urban-continuum,” which was populated by a substantial number of familial villages (Wong, et.al 2018, 1067). Tsin described Guangzhou as having an even more vibrant surrounding outside and not having a clear division of administration until Chen Jiongming took Guangzhou in 1920. Under the new mayor Sun Fo, son of Sun Yat-sen, who was heavily influenced by German city planners, Guangzhou was reconstructed into a city market (Guangzhou shi) that created a new spatial order to reflect the political rationality of modern cities (Tsin 2000, 19-29). However, the residential buildings that were built during the Republic period were usually turned into shanty houses of poor quality due to the Japanese invasion and lack of reconstruction (Cao 2015, 5-6).

Communist People’s Republic of China from 1949-1978

Urban areas during the Communist PRC were nationalized and usually followed the Soviet-style command economy and urban housing accommodation, or danwei houses (Cao 2015, 6). Although the size of cities remained limited due to Mao’s comment that “It’s no good if cities are too big,” (Naughton 1995, 64) cities in China followed the Soviet pattern of leaving the old city centers intact while increasing industrial buildup. Therefore, from 1965 to 1978, urbanization is characterized by Naughton as continued industrialization accompanied by minimal urbanization (Naughton 1995, 62-76). On the other hand, the danwei housing became the basic unit of society in urban China, which not only provided life-to-death care for urban workers but also provided an inward-looking network that created an acquaintance society among people living in the same danwei unit (Huang, 2017). The danwei housing in Guangzhou followed a similar pattern.

Reformist PRC after 1978

The dual-market structure and the parallel relationship between the decentralization of decision-making power and the definitive control of the central state are crucial for understanding the effects of land reform on urbanization in Guangzhou. The Land Reform in 1988, by which the state claimed tenure to the ownership of urban lands and the subsequent commodification of land that took place in 1992 provided the foundation for the rise of a real estate market in China.

Several works examine the complex set of dynamics of real estate development under reform (Gong 2006; Zhu 1999; Yeh 1995; Hsing 2010). Gong suggests that the dual structure gave the local governments the double identity to both act in line with central orders and to maximize local revenues by seeking opportunities to profit from the newly emerging market (2006, 85-7). The incompleteness of reform, on the other hand, is characterized by Zhu (1999, 82-144) as resulting in a gradual process, during which the central government utilized subsidies to phase out public housing such as danwei houses, while the local government adapted its policies to balance between economic development and changes in social demands. The coexistence of public housing and commercial land leasing is also characterized by Antony Yeh as a “dual land market” (Yeh 1995, 59-79). Adding another piece to the puzzle, Hsing suggests that land reform led to what she calls “territorialization” as a means for the local government to both gain administrative control and a major source of income (Hsing 2010, 5-19). Adding another piece to the story, Crawford calls for attention to the peasants whose farmland was taken and repurposed while some of them were left with only fragmented farmland and few opportunities to adapt to urban life (Crawford 257-262).

The dual structure and the strong public-private sector coalition are crucial for the understanding of Guangzhou’s urban shape. On the macro-level, urban planning follows the pattern of having multiple centers, as characterized by Gaubatz (1995, 47-60): downtown retail and business centers, new residential districts, targeted development zones, foreign enclaves, and restoration districts. Guangzhou’s expansion also follows the eastward and southward direction dictated by the 14th master plan (Liang 2014, 37-8). Nevertheless, due to the lack of a concrete and detailed city plan, the specific form and architectural development depended on the developers’ decision. As Yeh and Wu noted, “[t]he actual location, type and intensity of development may not be what the planners intended in the master and detailed plans, but rejecting a proposed building is difficult” (1995, 544). Similarly, Gaubatz suggests that, since Guangzhou didn’t have height restrictions except for buildings adjacent to traditional monuments, the overall profile of the city is greatly determined by commercial dynamics (1999, 1514).

Types of Urban Real Estate

Historic Districts and Urban Villages

In Guangzhou, historical districts and urban villages remain as the relatively “static” part of the city. The historical districts usually refer to the old cultural central axis in Yuexiu and Liwan, which is also where a lot of the elder population and those who are considered the “real Cantonese” (laoguangzhou 老广州) live (Huang 2017, 10-5). Though buildings with significant historical and cultural values were preserved, such as the foreign concession area and Qilou, buildings of less obvious historical significance faced the government’s attempt to renew because of their central location and dilapidated condition. However, redevelopment plans such as Jinghuajie , an old neighborhood that was redeveloped into a modern style shopping mall and a few high-level residential buildings, received heavy local criticism. The government responded by issuing a policy in 1999 to stop leasing out land parcels in the old urban core of Guangzhou, and many old neighborhoods were subsequently preserved (Liang 2014, 176).

On the other hand, a variety of literature discusses the socio-economic conditions in Guangzhou that gave rise to some strong village shareholding companies and bargaining power that maintained the urban villages’ foothold in the city (Hsing, 2010, 122-145). The urban villages were not only encompassed by the city as it expanded but also became housing for migrant workers and students from outside of Guangzhou. Regardless, the urban villages, along with the historical districts, continued to serve as a source of affordable housing for the low-income population in Guangzhou. Through a quantitative study, Song, Zenou, and Ding conclude that urban villages serve as an important source of affordable housing to people without urban hukou in Shenzhen, another coastal city in Guangdong (Song et.al 326-8, 2008).

Danwei Housing and Its Transformation

While the danwei housing also remained as a form of affordable housing, their form and status had more variation as they went through the land reform period. Many of the danwei housing units were sold at their net cost price (chengbenjia 成本价) to the firms that were associated with the danwei unit (Flock et.al 2013, 44). While many of the danwei housing units were resold to the workers at a higher price than the net cost price but lower than the market price, many were also transformed into affordable public housing that was aimed at easing the urban population to an increasingly privatized real estate market. On the other hand, many former industrial compounds underwent redevelopment plans that turned them either into restaurant areas or industrial parks for third industries (Huang, 2017). However, danwei housing is a relatively less studied area compared to urban villages, partly due to less obvious visual contrast, and partly due to their adaptive socio-economic status within the city.

Commodity Housing and Urban Expansion

The strong association between real estate developers and the local government is evident in a stream of literature. The relationship is evident in Hsing’s conception of “Socialist Land Masters,” the government institutions who own the land parcels directly, and “secondary developers,” the developers who had close relations to these landowners (2010, 35-8). Marketization gave rise to some local developers who had government connections, such as Country Garden (biguiyuan) and Star Rivers (xinghewan) (Liang 2014, 93-103). Wedeman also suggests that the relationship could lead to potential bribery when the official sought extra rent (or bribe) and would provide land usually much cheaper than the market price to certain developers (Wedeman 2013, 121-3)

The price of new commodity housing started to sky-rocket in the mid-2000s due to the macro-economic policies aimed at encouraging development. This stream of literature seeks to explain the policy implications of housing reform and resulting socio-economic and spatial patterns. In his extensive study of China’s real estate market, Cao examined the local government’s failure in providing affordable housing (ASH) due to the local government’s priority to maximize revenue from the real estate market and the lack of central guidelines (Cao 2015, 346-8). In addition, Zhou, Wu, and Cheng suggest that whereas residents in subsidized housing need to passively accept the job-housing mismatch, residents in commercial housing are actively engaging in a job-housing mismatch, which means that they actively choose to relocate to better housing with improvement in traffic conditions (Zhou and et.al 2013, 1833). Flock, Breitung, and Li’s study suggests that as affordable housing start to vanish in the inner city, high-class gated communities and displaced poor residents started to appear in the suburbs. They also discussed the affordability dilemma—a choice between the more affordable housing to satisfy the Chinese concept of home (jia) as a desired course of life and a less affordable option that demonstrates one’s ability to climb up the social ladder (Flock and et.al 2013, 45).

Conclusion

By examining literature discussing the evolution of real estate in China, or specifically Guangzhou, this review has sought to understand how different types of urban forms with different historical backgrounds and socio-economic implications, shape the city of Guangzhou. Historical districts are in the older districts of Liwan and Yuexiu in the West and urban villages scattered in the city remain as the relatively static part of Guangzhou. Danwei houses and part of the industrial compounds were transformed, adding a more vibrant and diverse kind of urban space while continuing to serve as affordable housing along with historical districts and urban villages. The birth, regulation, and boom of commodity housing, on the other hand, became the dynamic real estate that drives the city’s notable southward and eastward expansion. At the same time, driven by the growing real estate market, commodity housing in Guangzhou keeps influencing the socio-economic and spatial relationship between its residents and their physical location.

Note: The maps and illustrations are created by Huang. Huang demonstrates the pattern of urban expansion and compares them among different periods of urban real estate development in Guangzhou, as well as presents the dominating housing styles of their periods.

Bibliography

Cao, Junjian. The Chinese Real Estate Market: Development, Regulation and Investment. International Real Estate Markets. Abingdon, Oxon; Routledge, 2015. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315857855.

Crawford, Margaret. 2015. “Urban Agriculture in the Pearl River Delta.” In Food and the City: Histories of Culture and Cultivation. Dumbarton Oaks Colloquium on the History of Landscape Architecture; XXXVI. Washington, D.C: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

“Definition of REAL ESTATE.” Accessed November 5, 2021. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/real+estate.

Flock, Ryanne, Werner Breitung, and Li Lixun. “Commodity Housing and the Socio-Spatial Structure in Guangzhou.” China Perspectives 2013, no. 2 (June 1, 2013): 41–51. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.6172.

Gaubatz, Piper. “China’s Urban Transformation: Patterns and Processes of Morphological Change in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou.” Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 36, no. 9 (1999): 1495–1521. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098992890.

Gaubatz, Piper Rae. “Urban Transformation in Post-Mao China: Impacts of the Reform Era on China’s Urban Form.” In Urban Spaces in Contemporary China: The Potential for Autonomy and Community in Post-Mao China edited by Deborah Davis. Woodrow Wilson Center Series. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Gong, Ting. “Corruption and Local Governance: The Double Identity of Chinese Local Governments in Market Reform.” Pacific Review 19, no. 1 (March 2006): 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512740500417723.

Huang, Xin. “Transforming Danwei Housing: How Can the Old Residential Courts from the 1980s to 1990s in Guangzhou Respond to Diversified Demands in Urban Renewal?” 2017. https://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/object/uuid%3A18fd54eb-65d0-4999-aa15-3e4c092ee54b.

Liang, Samuel Y. Remaking China’s Great Cities: Space and Culture in Urban Housing, Renewal, and Expansion. Asia’s Transformations 43. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2014.

Naughton, Barry. “Cities in the Chinese Economic System: Changing Roles and Conditions for Autonomy.” In Urban Spaces in Contemporary China: The Potential for Autonomy and Community in Post-Mao China edited by Deborah Davis. Woodrow Wilson Center Series. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Skinner, G. William and American Council of Learned Societies. The City in Late Imperial China. Studies in Chinese Society. Taipei: SMC Publishing, 1995.

Song, Yan, Yves Zenou, and Chengri Ding. 2008. “Let’s Not Throw the Baby Out with the Bath Water: The Role of Urban Villages in Housing Rural Migrants in China.” Urban Studies 45 (2): 313–30.

Tsin, Michael. “Canton Remapped.” In Remaking the Chinese City: Modernity and National Identity, 1900-1950 edited by Joseph W. Esherick. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2000.

Wedeman, Andrew Hall. Double Paradox: Rapid Growth and Rising Corruption in China. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012.

Wong, Siu Wai, Bo-Sin Tang, and Jinlong Liu. “Village Redevelopment and Desegregation as a Strategy for Metropolitan Development: Some Lessons from Guangzhou City.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42, no. 6 (2018): 1064–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12633.

Yeh, Anthony Gar-On, and Fulong Wu. “Internal Structure of Chinese Cities in the Midst of Economic Reform.” Urban Geography 16, no. 6 (August 1, 1995): 521–54. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.16.6.521.

Yeh, Anthony Gar-On. “Dual Land Market and Internal Spatial Structure of Chinese Cities.” In Restructuring the Chinese City, edited by Laurence J. C. Ma and Fulong Wu. Routledge, 2004.

Zhou, Suhong, Zhidong Wu, and Luping Cheng. “The Impact of Spatial Mismatch on Residents in Low-Income Housing Neighbourhoods: A Study of the Guangzhou Metropolis, China.” Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 50, no. 9 (2013): 1817–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012465906.