Changsha: A Landscape of Consumption and Entertainment

During China’s Labor Day break, which is like Japan’s Golden Week, Changsha was ranked number six for the most popular travel destinations in the country. This might have come as a surprise for many people since Changsha is a city rarely known to those who live outside of China. Unlike the top-tier cities with large scale economy and cutting-edge industries, including Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Hangzhou, or touristic cities with rich history and beautiful scenery, including Xi’an, Ganzi, or Hulunbuir, the popularity of Changsha in today’s China may seem puzzling. The purpose of this report is to find a plausible explanation for this phenomenon.

The format of this report is largely inspired by Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project and Jordan Sand’s chapter “紳士協定――一九〇八年,環太平洋のひとの動き,ものの動き” in Everyday Life and Material Culture in Imperial Japan (帝国日本の生活空間). Changsha’s ascendency to an icon of popular culture happened only in recent years, so there is almost no systematic scholarship on this topic; at the same time, compared to top-tier cities or major cities in the east coast, Changsha usually receives much less attention from both Chinese and international scholars. Therefore, instead of establishing a linear explanation, this report adopts the montage technique to sequence a series of individual and unrelated pieces of information to better depict the way Changsha is portrayed and perceived. As Sand points out, a synchronic narrative more accurately captures people’s experience of acquiring and organizing information (Sand, 108-109). This observation is even more correct in today than the year 1908, which is the focus of Sand’s essay. A person today is likely to have learned most news from social media, phone notification, and short videos. These pieces of information are more fragmented and less in-depth than a conventional newspaper article. Instead of reading a well-researched article with a linear narrative on a single event, people are more likely to learn fragmented information about many individual events.

The popularity of Changsha is closely associated with these fragmented pieces of information on the internet. Just as the appearance of the crowd fundamentally transformed modern human beings and compelled Walter Benjamin to use the fictional flâneur figure as an observer of this new urban phenomenon, the same degree of impact can be said about internet as well (Simmel, 11-12; Frisby, 28-29). One label that is often attached to Changsha is wanghong (网红). This term can be roughly translated into English as “influencer,” albeit in Chinese it is used in multiple contexts and can function as both a noun and an adjective. By combining the Chinese characters wang (grid; internet) and hong (red; popular), wanghong was originally used to characterize those who became popular through livestreaming and then used for anything that is trendy on the internet and can thus generate huge profits. Changsha gained the name of “wanghong city” by creating countless IPs (intellectual property). IPs here in the context of the Chinese popular culture do not refer to the unique creations of the mind but anything, be it a person, a brand, or a work, that is widely known and can easily attract consumers. The success of Changsha thus largely hinges on its ability to create topics and attention on the net.

This report does not pretend to deliver an objective depiction of the real world. Dziga Vertov attempts to present an objective material world in his movie “Man with a Movie Camera” by getting rid of actors and intertitles; however, the way knowledge or “facts” are processed and assembled cannot help but reveal the unique perspectives of those who are consumers and producers of knowledge. Likewise, the pieces of information in this report are sequenced in an order that I believe can best reflect the argument I am trying to make here.

Changsha as a Ranked City

In a 2020 report named “Economy of Trends in China: Top 100 wanghong Cities in 2020,” Changsha is ranked number eight after Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hangzhou, Chengdu, and Xi’an (“Here Comes the Rank of Top 100 Influencer Cities in 2020”).

In a list of the ten “happiest cities” in China, Changsha is ranked number five after Chengdu, Hangzhou, Ningbo, and Guangzhou (“Announcing the Survey Results of the Happiest Cities in 2020 China”).

Chayan Yuese (茶颜悦色) as a Trending Topic on Weibo

Chayan Yuese, a Changsha based milk tea brand opened its branch stores in Wuhan and Shenzhen respectively in the last two years. Each time it became a trending topic on a microblogging service, weibo, the Chinese version of twitter. An analytical essay on Chayan Yuese’s popularity tells us that the topic on the branch store in Wuhan alone received more than a billion views and more than 100,000 discussion posts.

According to the article, there are several reasons to explain the success of Chayan Yuese: (1) high quality beverage; (2) customers always have the right to ask for a new cup if they are not satisfied with the taste; (3) the second cup of milk tea gets 50% off during rainy days; (4) co-branding with other famous milk tea brands as an effective way of marketing; (5) notifications about the length of queuing. For example, during the very day Chayan Yuese opened its branch store in Wuhan, it notified people that they had to queue for eight hours to buy a cup of milk tea. This can create an impression of “scarcity” and makes a branding strategy (“Opening a Branch Store Becomes a Trending Topic: How Can Chayan Yuese be so Popular?”).

Fig 1. Hashtag #The long queues outside of Chayan Yuese’s Wuhan branch store# became a trending topic on weibo on December 1, 2020.

Fig 2. “Album of Flowers and Birds.” The design of Chanyan Yuese is famous for its utilization of traditional Chinese art and aesthetic elements. (https://www.canva.cn/learn/package-design-milk-tea/).

Super Wenheyou: Building the Chinese Disney?

Super Wenheyou is not a typical city-center food court, but a small commercial world that is a fusion of night market, restaurant, museum, theme park, and street stores. It is a seven-storey building that occupies more than 5,000 squared meters of area and is filled with retro style decorations in 1980s style. Just like the Shin-Yokohama Ramen Museum (新横浜ラーメン博物館), nostalgia is an important part of Super Wenheyou. The founder of Super Wenheyou said during an interview that his goal is to “build a Disney in the Chinese food industry (“An In-depth Analysis |Disney in the Catering Industry: Super Wenheyou”).”

The co-founder of Super Wenheyou, Yang Ganjun, said that they spent eight years constructing this city of memories and dreams to restore culture, atmosphere, and shijing of old Changsha. In addition of eating crawfishes for which Wenheyou is famous, Super Wenheyou complex includes more than twenty different stores: barber shop, amusement arcade, dating agency, mahjong activity center, dance hall, hardware store, video room, theater, and etc. According to Yang, passenger flow at Super Wenheyou exceeds 10,000 people per day. The number of turnover rates is as high as 10 and there is almost no empty table between 11 am to 3 am (“An Interview with the Co-founder of Wenheyou”).

Fig 3. Interior decorations of Super Wenheyou (https://m.onewedesign.com/xingyezixun/13-906.html).

Wenheyou Stinky Tofu Museum

Wenheyou has a museum for stinky tofu (or “smelly tofu”). Stinky tofu is a famous streetfood dish in Changsha. According to a review of this museum, it includes a brining laboratory, a Manga presentation of stinky tofu production, experiencing “stinky smell,” and eating different flavors of stinky tofu. The museum also created a mascot and peripherals for stinky tofu. It may remind people of World of Coca-Cola in Atlanta (“A Review on Wenheyou Stinky Tofu Museum in Changsha”).

Fig 4. Wenheyou Stinky Tofu Museum (https://www.sohu.com/a/332441299_184791).

Fig 5. Brine laboratory. Brine making is an important part of stinky tofu production (https://www.sohu.com/a/332441299_184791).

First Sketches: Strolling Street

This part is an imitation of Benjamin’s “First Sketches, Paris Arcades” in his work The Arcades Project. It represents my unsystematic impressions of the Strolling Street as a native of Changsha.

Strolling Street conveys a shock of the crowd. The first impression anyone has about the Strolling Street is an endless stream of people. As the old Chinese saying goes: people mountain people sea (人山人海).

The crowd, however, does not indicate social contact. Unlike in a plaza, people are not supposed to talk with strangers in the Strolling Street. What the crowd creates is an atmosphere, the kind of atmosphere that is exactly the opposite of the Japanese mono no aware.

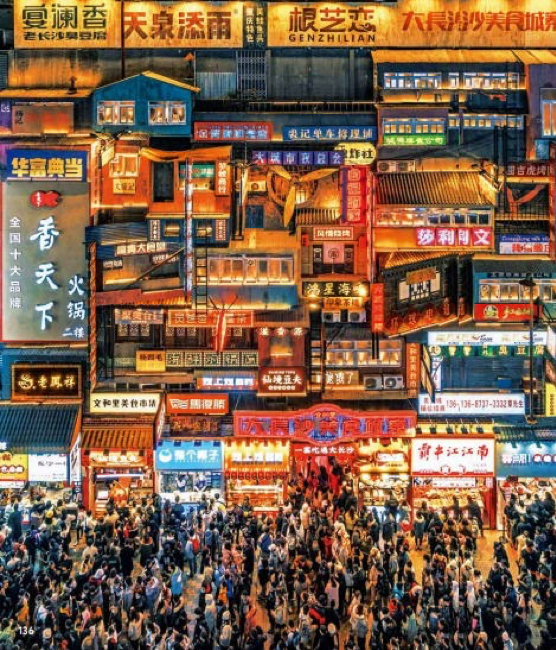

The signboards of the Strolling Street themselves create the scenery. There is something uniquely beautiful about neon lights at night. A cluster of signboards gives out impressions of abundance, streets, the crowd, and consumer culture. The view of signboards is famous in Hongkong and attracts many tourists. Hongkong became a source of design for the 1995 cyberpunk-inspired Japanese anime Ghost in the Shell. I think this is because signboards create a delicate balance between a modernistic impression and a crowded neighborhood.

Walking in Strolling Street utilizes a person’s multiple senses. The crowd in eyes, noises in ears, and most importantly, aroma of food in noses. One can buy almost anything in the Strolling Street, but street food is always the most important part of street culture.

Fig 5. Signboards in Strolling Street. Photo by Yuchen (weibo page: https://weibo.com/tyc414?refer_flag=1005050010_).

Smuggling Milk Tea Out of Changsha

On July 2021, media reported that there were businesses in Hangzhou profiting from smuggling Chayan Yuese’s milk teas out of Changsha. After receiving enough orders from customers, the smugglers would then take the bullet train to Changsha, purchase hundreds of cups of milk tea, put them in an incubator stuffed with ice, and go back to Hangzhou within the same day. A cup of milk tea can then be sold at a price of 60 yuan (roughly 9.42 USD), compared to the original price of 15 yuan (2.36 USD). Chayan Yuese made an official statement against the act of smuggling (“A Cup of Milk Tea’s Bizarre Journey from Changsha to Hangzhou: Is Trans-provincial Smuggling of ‘wanghong milk tea’ Legal?”).

Wenheyou’s Branch Store in Shenzhen: a “Super Queuing Complex”

Super Wenheyou implements an online reservation system during its opening day of the first branch store in Shenzhen on April 2, 2021. The online system showed that there were more than 50,000 queuing numbers in that day (“Wenheyou: A Super Queuing Complex”).

Fig 7. “You have 53,254 people queuing before you, please wait patiently”

The Expansion of Changsha’s Food & Beverage Brands

Shi Ge points out in an article on YiMagazine, “Why Nationally Famous Food & Beverage Brands All Come from Changsha” that many Food & Beverage brands born in Changsha successfully expanded into top-tier cities like Beijing and Shanghai. The financing scale of these companies range from two billion CNY to ten billon CNY. They include Chayan Yuese, Wenheyou, Feidachu (Hunan Cuisine), Dim Sum Bureau of Momo (Chinese baking), and Santurnbird (Changsha’s native coffee brand).

Some Thoughts

This part reflects some of my thoughts on Changsha as a landscape of Consumption and Entertainment. It does not equate to a “conclusion,” a usual ending of a research essay or report. To reach a conclusion on something means that a researcher needs to collect some kind of evidence or facts for it; on the other hand, this indicates that evidence only becomes meaningful when there is a conclusion as its logical destination. This experimental report, on the contrary, centers around fragments of information we have come in contact during daily life.

Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression is a widely cited book for recent flourishing writings on archival thinking. Quite ironically, archives and their meaning to historians do not constitute the main argument of his book. Drawing on Freud’s “A Note on the ‘Mystic Writing-Pad’,” a piece that establishes an abstract connection between human memory structure and the mystic writing-pad, Derrida contemplates the deep connection between archivization and psychoanalysis. Derrida’s etymological analysis of the Greek word arkhē shows that it means both commencement and commandment. The archive, “on account of their publicly recognized authority, it is at their home, in that place which is their house, that official documents are filed. The archons are first of all the documents’ guardians. They do not only ensure the physical security of what is deposited and of the substrate. They are also accorded hermeneutic right and competence” (Derrida, 2). Therefore, archive was originally situated in a privileged domiciliation over which archons wielded the power of commandment. An archive is also inherently public. Going to an archive means to enter a public space. Just like Derrida was focusing on the impact of e-mail, social medias we have today fundamentally challenge this past concept of archive. The boundary between private and public is no longer clear and one social media account indicates a version of archivization. The trending events on a micro-blogging service can be interpreted as an active and real-time process of archivization. Physically, companies like Chayan Yuese and Wenheyou are largely confined in one city, Changsha; on social media, however, they are already well-known across the country. This is the context in which smuggling, super queuing complex, and Changsha as an “influencer city” happened.

There is another interesting question to think about: why do people pay so much attention to food & beverage? In an interview with Yang Ganjun, the co-founder of Wenheyou, he frequently mentioned shijing. The word is a combination of shi 市 (market; city) and jing 井 (wells). This indicates a fusion of market and neighborhood. In many traditional Chinese cities, they were not separated from each other. Shijing, as a place where ordinary people live, also conveys a sense of ordinariness. In Japanese, for example, “市井の人 shisei no hito” simply means ordinary people. It explains why Super Wenheyou, a large project of retro-style complex, is frequently associated with shijing. It also explains why Strolling Street must be an experience of aroma. Street food is closely connected to shijing, ordinary people, and popular culture. There is something reassuring and relaxing about eating while wandering around on the street. Waiting in a queue for street food is a frequent sight in Changsha, especially Strolling Street. Some people have a negative response to it: “We have better things to do than that.” This may be true, but idling itself is also a lifestyle. A lifestyle that people believe they had in the past that is increasingly disappearing in the present.

Bibliography

- Sand, Jordan. “紳士協定――一九〇八年,環太平洋のひとの動き,ものの動き,” in 帝国日本の生活空間. 岩波書店, 2015.

- Simmel, Georg. “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” in The Blackwell City Reader edited by Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson. Oxford and Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2002.

- Frisby, David. “The City Observed, the laneur in social history,” in Cityscapes of Modernity: Critical Explorations. Polity, 2001.

- Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Belknap Press, 2002.

- Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- “2020网红城市百强榜来了 (Here Comes the Rank of Top 100 Influencer Cities in 2020 )” Accessed December 1, 2021. https://m.21jingji.com/article/20200706/herald/b63abcb2a1ea1288caffb753f141b442.html.

- “ ‘2020中国最具幸福感城市’结果发布 (Announcing the Survey Results of the Happiest Cities in 2020 China ).” Accessed December 1, 2021. http://www.xinhuanet.com/local/2020-11/20/c_1126767223.htm.

- “开店即热搜,茶颜悦色凭什么这么火?(Opening a Branch Store Becomes a Trending Topic: How Can Chayan Yuese be so Popular?).” Accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.socialmarketings.com/articldetails/10250.

- “深度解析|餐饮界的迪士尼:超级文和友 (An In-depth Analysis |Disney in the Catering Industry: Super Wenheyou).” Accessed December 1, 2021. http://www.foodaily.com/corpnews/show.php?itemid=5463.

- “一杯奶茶从长沙到杭州的奇幻之旅 跨省代购“网红奶茶”违法否 (A Cup of Milk Tea’s Bizarre Journey from Changsha to Hangzhou: Is Trans-provincial Smuggling of ‘wanghong milk tea’ Legal? ).” Accessed December 1, 2021. https://finance.sina.com.cn/tech/2021-07-17/doc-ikqcfnca7329425.shtml.

- “文和友,一家超级排队综合体 (Wenheyou: A Super Queuing Complex).” Accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.36kr.com/p/1167060157777025.

- “探店长沙文和友臭豆腐博物馆(A Review on Wenheyou Stinky Tofu Museum in Changsha).” Accessed December 22, 2021. https://www.sohu.com/a/332441299_184791.

- “专访文和友联合创始人 (An Interview with the Co-founder of Wenheyou).” Accessed December 22, 2021. http://news.winshang.com/html/064/1973.html.

- “为什么大热消费品牌都来自长沙?(Why Nationally Famous Food & Beverage Brands All Come from Changsha).” Accessed December 22, 2021. https://www.yicai.com/news/101232122.html.