During the Second World War, Changsha was the most badly damaged city along with Stalingrad, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki. It is also the first major world city that suffered total war destruction during the Second World War (Hudson, 92). Under the directive of “scorched earth policy (jiaotu kangzhan 焦土抗战)” by Chiang Kai-shek, the local security force torched Changsha at midnight of November 12 in 1938. The 1938 Changsha Fire or wenxi dahuo (文夕大火) destroyed most of Changsha’s neighborhoods. Changsha then became the pivot of the Sino-Japanese War during 1939-1944 due to its strategic importance. The Chinese army was able to hold this city and claimed victories in three battles of Changsha against the invading Japanese army until the city’s fall in 1944, which was only one year away from the Japanese surrender. As important as Changsha was, there are relatively few works on Changsha in the historiography of World War II. One reason to explain this phenomenon is that the 1938 Changsha Fire is an embarrassing event for the Chinese side. Unlike Stalingrad, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki, which were destroyed out of direct war confrontation, torching Changsha turned out to be a false move since the Japanese army was not approaching the city at the time. The First Battle of Changsha happened nine months after the fire. Thus, the 1938 Changsha Fire is not considered as a case of wartime destruction and becomes significantly less important to public memory than events like the Rape of Nanjing. Likewise, aside from the fact that the importance of the China theater is underestimated in the studies of World War II, the battles of Changsha are overshadowed by allies’ major offensive operations after 1943. This explains why the four battles of Changsha receive little attention from the public and academia in China and abroad. This review attempts to present a preliminary re-interpretation of the relationship between Changsha and the war. Instead of interpreting the 1938 Changsha Fire as simply an embarrassing mistake, it understands the fire as a kind of war destruction that results from military strategies and terror. I will also argue that the battles of Changsha not only signified a new stage of the Sino-Japanese War, they also helped contributed to the revitalization of Changsha. War, therefore, is not always associated with destruction and death, but can also lead to reconstruction and rejuvenation.

Hunan as a War Front

Following the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Japanese forces marched toward China from Manchuria and assaulted major coastal cities, including Shanghai and Nanjing. The pressures from north and east compelled the Nationalist government to transfer heavy industries and educational institutions toward interior regions. Hunan, an interior province, was an excellent transition point or destination for this transfer plan since it was still far from the battlefronts. As a result, one third of the factories in coastal regions were transferred into Hunan; they included machine building, ordnance, textile, and mining industries (Wang Guoyu, 356-374; Tan, 712-718). Changsha as the political and historic center of Hunan also attracted prominent intellectual elites throughout the nation as a safe haven. By engaging with journalism, educational movements, patriotic operas and plays, they made Changsha what Tan calls the capital of “cultural resistance to Japanese imperialism” and civic nationalism (Tan, 719-733). Prestigious educational institutions moved into Changsha as well. For example, Beijing University, Tsinghua University, and Nankai University together formed a temporary university in Changsha; they would later move to Kunming and became the famous National Southwest Association University (Tan, 735-736).

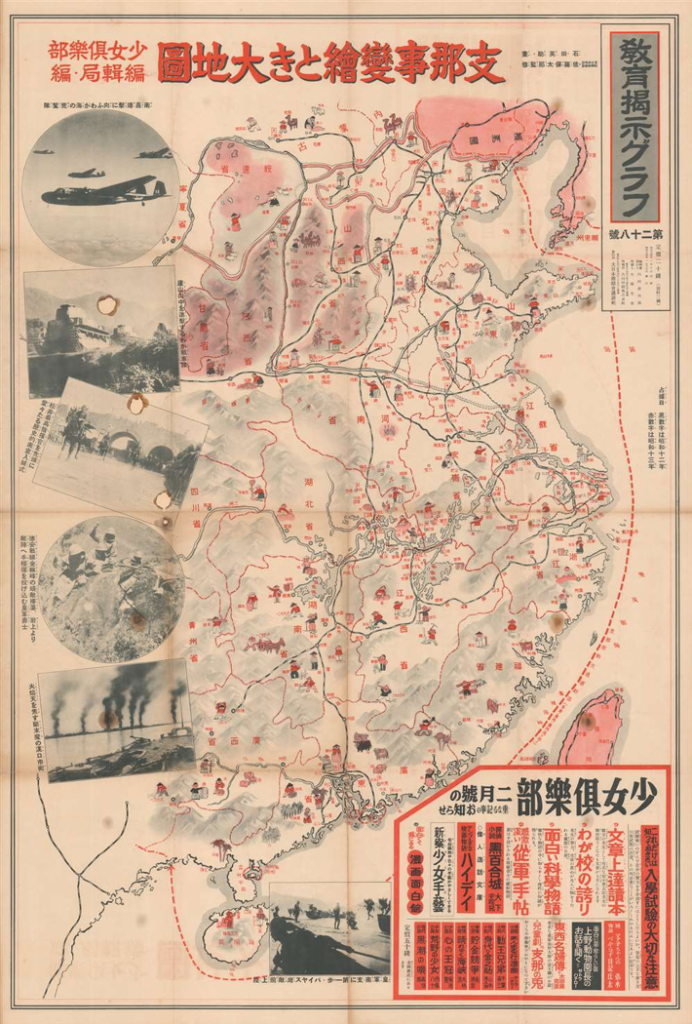

Hunan and Changsha’s status as an interior base shattered after the fall of Wuhan in 1938. The Japanese force occupied Guangzhou at approximately the same time. This development suddenly put Changsha in the spotlight. Since Changsha was the mid-point of Wuhan-Guangzhou railroad, it became an essential connecting point between two battle theaters in China for Japan. As Figure. 1 shows, the Japanese control extended from Manchuria to Hainan island, but it had not yet penetrated into Hunan, which served as a wedge that separated occupied territories. Hunan also functioned as an effective barrier to China’s wartime capital, Chongqing, which located in the southwest. Changsha thus became the next major strategic objective for the Japanese force (Xing and Xu, 20-21). This transformed Hunan from an interior base into a battlefront.

Fig 1. 支那事變繪とき大地圖. A 1939 map of China and the Second Sino-Japanese War, published on Shōjo Kurabu (少女倶楽部), a Japanese girls’ magazine. Rising-sun flags are placed on the occupied large cities (https://www.geographicus.com/P/AntiqueMap/china-kodansha-1939).

Massive currents of refugees flowed into Hunan. 26 percent of population in China was forced away from their home or native places during the war, and Hunan had one of the highest refugee populations (Hudson, 94). As a result, the population of Changsha rose to 500,000, an all-time high figure. In addition to refugees, many wounded soldiers retreated to Changsha from battlefields. Unfortunately, due to the lack of medical facilities and funding, many of them were not able to receive fair and appropriate treatment. The famous writer Zhou Libo, for example, witnessed a soldier who had lost a leg put a knife into his throat because his money was stolen by a lieutenant and no one was willing to help him (Wang Yanitai, 41-42). The existence of massive numbers of refugees and wounded soldiers caused social stability to deteriorate. This was further confounded by Japanese bombing. Seven bombings were recorded from November 24, 1937 to August 27, 1938 (Hudson, 95-96; Wang Yanitai, 43-46). Japanese bombings destroyed key facilities in the city, contributed to war terror, and added difficulties to the refugee relief work.

The Changsha Fire as a War Destruction

The biggest destruction to the city, however, was the 1938 Changsha Fire, carried out by the KMT officials. It was estimated that three thousand people died in the fire. There were not enough transportation vehicles to evacuate those who stayed in the city. Many people who escaped to the Xiang river were not able to cross it because of the limited number of boats, and some of them drowned to death. The same happened to those who attempted to escape by train. The train was overcrowded with people and many had no choice but to stand on the front, back, and top of the train. A lot of them were killed on the railroad when they fell off from the train. It is unclear how many people died because of the fire. Estimates range from 2-3000 people to 7000 people. (Wang Yanitai, 71-82; Hudson, 97-98). More than 95 percent of the houses were destroyed, and 60 percent of neighborhoods completely disappeared. The fire also wiped out almost all government buildings, educational institutions, and the financial district (Chen, 62-64; Wang Yanitai, 100-112). As a three-thousand-year-old city with rich history, most of its ancient relics were destroyed by the fire as well.

It is impossible to identify the culprit of this fire. The municipal government devised a plan to torch the city under the directive of Chiang Kai-shek’s “scorched earth policy.” The “scorched earth policy” had a solid historical basis in Republican-era China. Given China’s weaker economy and poorly equipped army compared to imperial powers, many people believed that China should utilize its vast territorial size and “scorched earth policy” to land a fatal blow to its enemy. The famous Hunanese general, Cai E (蔡锷), for example, suggested that China should learn from Boers in the Boer War or Russians in the 1812 campaign. The Russians, of course, burned Moscow during Napoleon’s invasion in 1812. Li Zongren, one of the most powerful Chinese generals at the time, was also a strong supporter of “scorched earth policy” when the Second Sino-Japanese War started (Yang, 38-39). During the Nanyue Meeting on November 1, Chiang Kai-shek made the decision to evacuate government employees and residents from Changsha to Yuanling in West Hunan; he also authorized Zhang Zhizhong, the provincial governor of Hunan, to burn the city if the Japanese force was approaching. Therefore, the evacuation was already underway before the fire. However, most people did not know the plan to torch the city, which remained a secret. On November 11, the Japanese occupation of Yuezhou, a city that was only 200 kilometers away from Changsha, escalated the situation and conveyed to the KMT a message that there was an imminent Japanese threat. In the following day Zhang Zhizhong received a telegraph from Chiang Kai-shek who again asked Zhang to torch the city if the Japanese approached. The actual plan of torching the city was devised the afternoon of the same day —— less than 12 hours before the city started to burn. The fire turned out to be an accident, however. There were still 30,000 people left in the city. Zhang Zhizhong, who was having dinner with foreign missions’ community members that night, just a few hours before the fire, asked them to evacuate the city the next day. Therefore, the provincial governor must have planned to wait at least a few more days before carrying out the fire plan (Wang Yanitai, 113-155; Yang, 42-45; Hudson, 99-100).

Fig 2. The ruins of Changsha after the fire (https://wemp.app/posts/abdd4889-f533-45b0-b350-ba78c981b9b7?utm_source=latest-posts).

Fig 3. A child sits in the ruins (https://wemp.app/posts/abdd4889-f533-45b0-b350-ba78c981b9b7?utm_source=latest-posts).

Nobody knew who started the first fire since kerosene and torches were already distributed among the military police, who were responsible to carry out the fire plan. Multiple accounts attested that numerous fire teams made up of military police or security soldiers set fire to the houses (Wang Yanitai, 113-155; Hudson, 97-100). Even the island in the middle of the Xiang river was set on fire. The plan was hastily made but frightfully well carried out. It is not this article’s purpose to trace responsibility for the fire, which is an extremely difficult question to answer; instead, we should focus on how the war had turned Changsha into an unstable ticking bomb, waiting for explosion. The “scorched earth policy” and the perceived threat of imminent Japanese attack led to the plan to torch Changsha. This enabled hundreds of poorly instructed soldiers to receive flammable materials in a hasty fashion. Since most government workers were already evacuated from the city, there were no policemen to patrol the street or maintain order. What further confounded the situation at the time was the war terror resulting from Japanese bombing and rumors of an attack. Many people attested that they heard a rumor of Japanese reaching the Xin river (新河), which was two kilometers away from Changsha; in fact, the Japanese force reached the Xinqiang river (新墙河), which was still two hundred kilometers away from Changsha (Wang Yanitai, 182-186). The difference of merely one Chinese character was able to cause much larger an impact of terror. What developed, then, was an uncontrolled city, ready to be abandoned, that was full rumors and flammable materials. The Changsha Fire should therefore be interpreted as a case of war destruction that was caused by Chinese strategic goals, Japanese military operations, perceived threat, and war terror.

The Battle of Changsha and the Rejuvenation of Changsha

The reconstruction of Changsha started almost immediately after the Changsha Fire. Both the government and non-state actors contributed to the revitalization of Changsha. Chiang Kai-shek ordered the municipal government to clean the ruins as soon as possible to restore the city transportation (Yang, 48-49). As a result, at the end of November, train station, postal service, and telegraph resumed. The municipal government formed the temporary committee of relief; the committee prepared 1000 bags of rice, 500 bags of salt, and 1000 tons of coal to help the refugees (Tan, 653-654). The government efforts were assisted by non-state actors. For example, the secretary of Changsha YMCA (Young Men’s Christian Association), Zhu Tierong, helped distribute government relief money to refugees. She recalled that 90,000 refugees were able to receive relief money in one day in an orderly fashion (Wang Yanitai, 317-318). Foreign missions including the Hunan Bible Institute, the Roman Catholic Mission, and Yale-China Association established their own relief centers, and in return they received aid and loans from the Nationalist government (Hudson, 107-108).

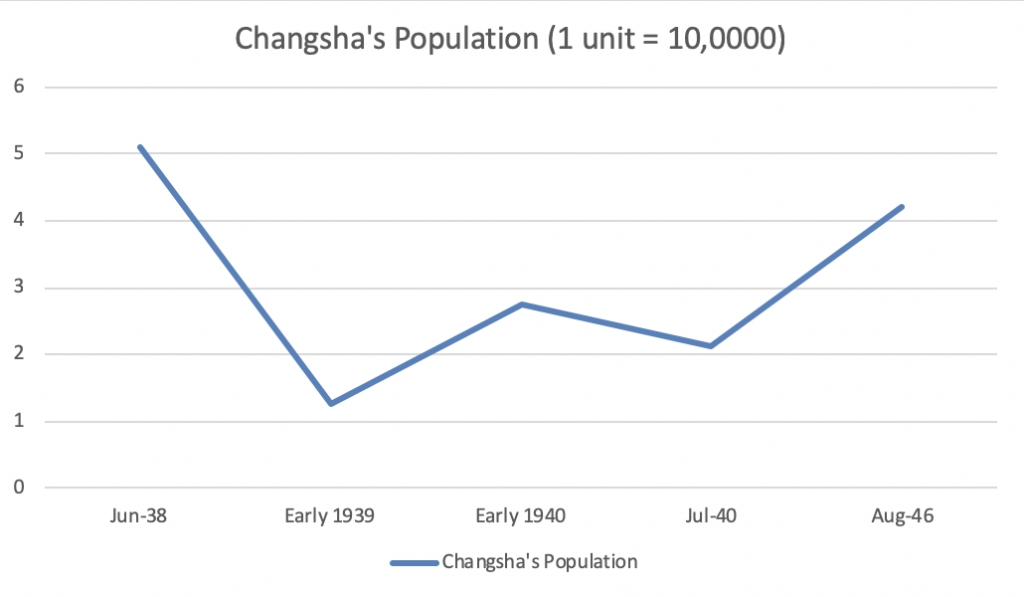

After the Changsha Fire, Zhang Zhizhong was discharged and Xue Yue became the new governor of Hunan. This helped resistance to the Japanese attacks against Changsha not only because Xue Yue strongly resisted abandoning Changsha without a fight but also because Xue Yue was at the same time the regional military commander. Secrecy was the reason why the fire plan had been so lethal. Only Zhang Zhizhong and military police knew the plan to torch the city; the city government and the army were completely in dark. This removed any possible check on the execution of the fire plan and prevented the governor from acquiring the newest information about the Japanese army. In contrast, by being both the provincial governor and the regional military commander, Xue Yue utilized every possible resource to ensure that his efforts to engage a battle with the Japanese force and the rebuilding of Changsha could be complementary to each other. The three battles of Changsha enabled China to maintain a stalemate with Japan. This is what Chiang Kai-shek called the “second phase” of Sino-Japanese War. The strategic goal of Japan also shifted to securing occupied areas and weakening the Chinese force as much as possible (防衛厅研修所戦史室, 339-341). As a result, Changsha was able to secure approximate five years of peace, which were essential for the revitalization of the city. By 1946, one year after the war ended, the population of Changsha had almost bounced back to the pre-war level.

Table 1. The Population of Changsha (湖南省抗战时期人口伤亡和财产损失, 10)

War Legacy

In 2005, a monument in memory of the 1938 Changsha Fire was erected in Tianxin Park, one of the most damaged area during the fire. The monument consists of two parts. One is an “warning bell” and another is a separate city relic. Both of them aim to remind people of the historical lesson of the fire. However, the monument soon became an object of graffiti art and vandalism. An article in 2013 reported that the inside of the bell was full of inscriptions left by couples or tourists (Li). For many residents the warning bell is probably not much different than other monuments in the city and it thus fails to stand for a historical lesson. Nor are the marks of war or fire visible in the city. Most of the historical structures destroyed in the fire were rebuilt after the war. The rapid urbanization initiated after the 1980s brought more impacts on the city than the war or the fire could ever have. Today, urbanization and modernization pose new threats toward historical relics.

The historical memories about the fire and battles of Changsha are equally elusive in Japan. A quick search of the word “長沙作戦 (Battle of Changsha)” in CiNii yields only one article “日中戦争 長沙作戦 : 日本陸軍の作戦立案の限界を示した”鉄壁の城”への攻勢” published on Rekishi Gunzō (歴史群像), a non-academic magazine. A search of “長沙大火 (Changsha Fire),” however, yields nothing. I managed to find three books on battles of Changsha or central China front: 湖南戦記―知られざる日中戦争のインパール戦(Battle Record of Hunan—the Unknown Battle of Imphal of Sino-Japanese War ) by Kodaira Kiichi (小平喜一); 長沙作戦 緒戦の栄光に隠された敗北 (Battle of Changsha—A Defeat Hidden in the Glory of the Early War) by Sasaki Harutaka (佐々木春隆); 華中作戦―最前線下級指揮官の見た泥沼の中国戦線 (Central China Warfront – The Muddy Chinese Battle Front a Junior Commander Saw in the Frontline) by Sasaki Harutaka. However, both of these authors, Kodaira Kiichi and Sasaki Harutaka, participated in the battle of Changsha, so writing these books probably mean more to themselves than to the public. From the titles alone, one can tell the battle of Changsha was perceived by Japanese as a major defeat as well. Kiichi even compares it to the battle of Imphal, which was another heavy defeat of the Japanese force in British India. The battle of Changsha is also “unknown” and “hidden” to the public.

The Changsha Fire remains an “embarrassing” event for the Chinese. After all, it is Chinese themselves who torched the city. There are also contrasting opinions on the torching itself. Wang Yanitai interviewed scholars in Changsha and listed several focal points of this debate: (1) Did the fire, to some degree, manage to hinder the march of the Japanese force? (2) Is it justified to commit the “scorched earth policy” in order to resist Japanese invasion? (3) How should we understand the Changsha Fire in a historical and comprehensive fashion? One group of scholars believed that the Changsha Fire demonstrates the great spirit of Chinese people who could endure tremendous sacrifice during the resistance war against Japanese. Torching the city was a correct decision in this view because we should leave nothing for the Japanese to use against us. Torching Changsha might have helped slow down Japanese invasion because a burned Changsha has no value. Another group of scholars, however, assert that the fire exerted great harm upon people and it in effect did nothing to stop Japanese invasion (Wang, 260-268).

Regardless of how scholars view the Changsha Fire today, the fire actually marked the end of the “scorched earth policy.” The Nationalist government never attempted to torch any of their own cities after the 1938 fire. The fire was perceived in a very negative light at the time and was later used by the Communists to accuse the Nationalist government of being corrupted, unorganized, and incompetent. However, the larger debate on this issue reveals an ethical dilemma. Does the government have the power and right to torch its own people’s home during a defensive war? We can compare this question with the equally if not more controversial decisions on dropping nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or aerial bombings on civilian areas. The 1938 Changsha Fire and battles of Changsha, therefore, deserve more attention from the public and academia since they pose questions that deserve further exploration.

Bibliography

- Wang Yanitai. 长沙文夕大火(The Changsha Fire). Beijing: 商务印书馆, 2016.

- Xing Ye and Xu Haiyun. 长沙会战 (Battle of Changsha). Beijing: 航空工业出版社, 2016.

- Hudson, James. J. “The Early War Resistance of Changsha YMCA, 1937-41.” Journal of Chinese Military History 6, no.1 (2017): 90-113. https://doi-org.proxy.library.georgetown.edu/10.1163/22127453-12341309.

- 防衛庁研修所戦史室. 香港・長沙作戦 (Battle of Hongkong and Battle of Changsha). 朝雲新聞社, 1971.

- Tan Zhongchi. 长沙通史. 现代卷 (A Comprehensive History of Changsha, 1919-1949). Changsha: 湖南教育出版社, 2013.

- Wang Guoyu. 湖南经济通史.现代卷(An Economic History of Hunan, 1919-1949). Changsha: 湖南人民出版社, 2013.

- Shen Xiaoding. 一个城市的记忆——老地图中的长沙 (The Memories of a City: Changsha in Old Maps). Changsha: 湖南大学出版社, 2018.

- Chen Xianshu and Liang Xiaojin. 老照片中的长沙 (Changsha in Old Photos). Changsha: 湖南人民出版社, 2016.

- 湖南省抗战时期人口伤亡和财产损失 (Casualties and Properties Loss of Hunan Province during the Second Sino-Japanese War).

- Yang Weizhen. “1938年長沙大火事件的調查與檢討 (Revisiting the Case of the 1938 Changsha Blaze Incident).” 國史館館刊 33 (2012): 33-56.

- “纪念长沙文夕大火80周年.”Accessed December 22, 2021. https://wemp.app/posts/abdd4889-f533-45b0-b350-ba78c981b9b7?utm_source=latest-posts.

- Li Tang. “天心阁警世钟内外各有乾坤.” Accessed December 22, 2021. https://hn.qq.com/a/20130528/006236.htm.