QUESTIONS:

Does Beijing have a single overall plan? When was it made and with what aims?

What remains of it today?

How should we understand the relationship between protecting historical heritage and modern development?

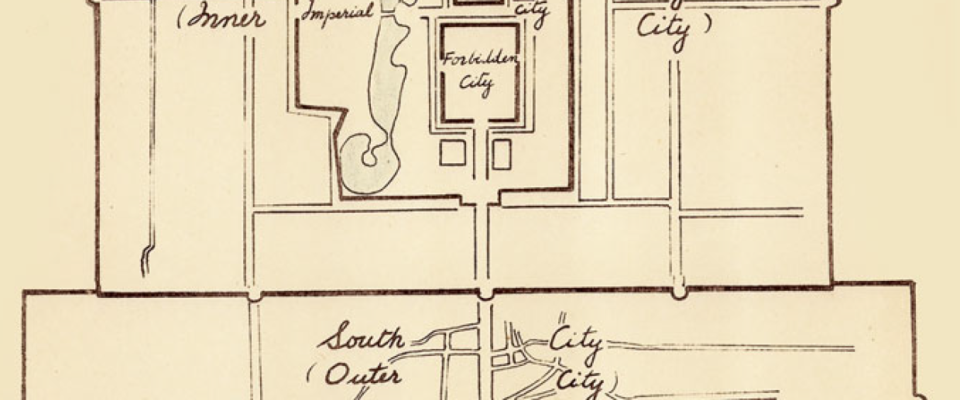

Modern Beijing, which took shape based on Mongol Khanbaliq, was finally established after the Ming’s reconstruction (Hou 2014, 96). During the reconstruction, the city shrank its northern part and then expanded southward (Hou, 97). In 1420, the northern part of Beijing was built. Three city walls further divided the space into the Forbidden City, the Imperial City, and the Inner City. With the accomplishment of the Outer City in 1553, the present form of Beijing was virtually completed. There was no further construction until the PRC period (Hou, 105).

The city walls, which surrounded Beijing for more than 400 years, were the most important part of the character of the city. The walls not only defined the boundaries of Beijing but also divided Beijing into many enclosures. As Susan Naquin summarizes, Beijing was a city of “walls within, walls without, enclosure nested inside enclosure, cities within cities (Naquin 2000, 6).” Several works focus on discussing the function and meanings of the city walls. The first consideration in constructing Beijing’s walls was to ensure the city’s safety. During the Ming period, the walls were used to defend against Mongol and Manchu raiders. Thus, the first impression created by Beijing’s walls was one of protection, enclosure, and safety, as the walls were very imposing (Naquin, 7).

Moreover, the walls are also interpreted as an expression of an imperial ideology by scholars. Based on emphasizing the emperor as the “cosmic pivot,” the city walls helped define Beijing, the capital city, as the mirror of the cosmos which the imperial power ruled (Naquin, 7). And the enclosures that the city walls made, as Wu Hung argues, could also be seen as an obsession with keeping the imperial power secret (Wu 2005, 57). The walls were layers of barriers that repeatedly separated “inner” from “outer,” which became the defense of imperial power. As Wu suggests, the walls not only ensured outsiders never gained access to power but also made the emperor invisible to the public and thus strengthened his divine authority (Wu, 58). Besides, some of the walls also helped divide the urban space into different functional divisions, especially between inner and outer cities. The Inner City functioned as a residential area, and the Outer City held commercial activities (Naquin, 9). And after the Manchu established a new authority in Beijing, this wall also separated residences of different ethnic groups. The Manchu, primarily elite, lived in the Inner City, and the Han civilians lived in the Outer City (Naquin, 10).

Though the city walls fulfilled the duties of ensuring Beijing’s safety and creating order inside the urban space, they also created difficulties for the public to develop civic life. As Naquin describes, Beijing’s residents usually lived inside the narrow alleyways cut by the walls, and the multiple sets of walls became inconvenient barriers to easy movement that residents encountered daily. Therefore, as Naquin argues, the city may have had multiple centers rather than a single one since the walls had divided the city space into fragments (Naquin, 8). In addition, the walls also cut off the communication between the city and the countryside around it, which created difficulties to develop ordinary social and commercial intercourse. According to Naquin, as the city planning valued security and order over convenience, the tension between political concerns and developing ordinary civic lives became a problem that remained for several centuries (Naquin, 10). And the tension, accompanied by the changing position of Beijing city, finally caused further actions to the city walls during the modern era.

After the Eight-Nation Alliance occupied Beijing in 1900, the demolition of the city walls began, which was accompanied by the construction of railroads. In order to direct the train to the foreign army headquarters, which settled inside the Inner City, a railroad, started from Tianjin, physically broke the city walls east to the Yongding Gate in 1900. In the same year, another rail line was brought into the city walls at Zhengyang Gate (Dong, 2003, 35). As Dong suggests, the railroads permanently shook the city walls, causing the walls to lose their practical functions and symbolic meanings. By 1930, seven gateways had been opened, and the protective walls of all Inner City gates had been either dismantled or pierced to give way to rail construction (Dong, 37). While the railroads broke the city walls from without, upgrading old streets and building up modern transportation achieved the same effect from within. According to Dong, the Imperial City walls were almost gone in 1927 because of the road widening project (Dong, 42). And by 1937, nine new openings were added to the walls due to the construction of streetcars and railroads (Dong, 41). The dismantling of Beijing’s city walls also meant the dissolution of imperial power. With the fall of the Qing Empire in 1912, Beijing had lost its privilege as the political center and had to redefine itself in a new role. As Dong argues, the demolition of city walls helped the cell-like, fragmented space inside Beijing be ideally connected, and it also helped build a smooth connection with suburban areas near Beijing (Dong, 53). In all, the changing position of Beijing made the original function of city walls obsolete, and the dismantling of city walls also showed the accelerating process of Beijing’s transformation into a modern and self-governed city.

Fortunately, Beijing’s remaining city walls survived during the Japanese occupation. However, after the foundation of the People’s Republic of China, the communist government decided to rebuild Beijing. A controversy was raised over whether the new Beijing should preserve or demolish the old city walls. In 1950, the famous Chinese architect Liang Sicheng published an article calling for protecting the city walls. According to Liang, Beijing’s city walls were valuable historical heritages that should be preserved, and the coexistence of city walls and the development of the modern city were not contradictory. In his blueprint, Liang planned to transform the city walls into civic parks, thus increasing the modern city’s green area (Wang 2011, 136). Though many architects had provided possible city plans, the communist political ideology (or Mao’s own ideology) took the lead during the whole reconstruction process. After Mao insisted on placing the nation’s governing body inside the old city, the reconstruction of Tiananmen Square began. Several walls and gates used to surround the square were dismantled during the 1950s. As Wu Hung suggests, the demolition of walls was considered a symbolic gesture to destroy the past (Wu, 23). Besides, with the advice of Soviet specialists, the communist government decided to position the city as a new industrial center of China. In order to carry out further industrial construction, the dismantling of Outer City walls began at the end of 1953 (Qu 2005, 67). Moreover, the unstable international environment and the irrational political movements during the late Mao period had made the communist government accelerate the dismantling process of Beijing’s city walls. The government decided to tear down all the city walls except a few sites and used the bricks to support munition and industrial productions (Qu, 67). By 1979, only three sites of city walls existed in Beijing, while other parts of the walls all became ruins. Though Qu points out the objective reason that Beijing’s city walls had to be torn down due to safety concerns, both Wang and Wu placed the political factor as the most significant reason for dismantling the city walls (Qu, 69; Wang, 333; Wu,23). In all, during the Mao period, Beijing’s city planning was highly influenced by political ideology. As the communist government decided to reposition Beijing as the political and industrial center, the main idea of reconstructing Beijing during the Mao period was to cut off the past and turn Beijing into a modern communist city.

To conclude, according to the sources discussed here, the building and dismantling of Beijing’s city walls were highly dependent on Beijing’s city positioning and the leading political ideology, which changed over time. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the city walls were the expression of imperial power. In the modern era, the city walls became obstacles to Beijing’s becoming a modern self-governed city. And after the foundation of the People’s Republic of China, Maoism viewed the city walls as a past remnant that must be destroyed to fit the new communist China. Interestingly, none of these authors discuss Beijing’s city walls today. Both the public and the government have begun to view the walls as important historical heritage and a symbol of Chinese culture. In 2004, the Yongding Gate, which was dismantled in 1957, was rebuilt in the original site. What does the rebuilding mean, and how to understand the relationship between historical heritage and modern city development? These are the questions that both the public, architects, and the government must continue to consider.

Bibliography:

Dong, Madeline Yue. Republican Beijing: The City and Its Histories. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Hou, Renzhi. A Historical Geography of Peiping. Heidelberg: Springer, 2014.

Naquin, Susan. Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400-1900. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Qu, Wanlin. “Controversy and Results: History Review on Beijing’s Wall after the Foundation of the People’s Republic of China,” Social Science of Beijing, no. 4 (2005): 62-70. CNKI.

Wang, Jun. Beijing Record: A Physical and Political History of Planning Modern Beijing. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co., 2011.

Wu, Hung. Remaking Beijing: Tiananmen Square and the Creation of a Political Square. London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2005.