QUESTIONS: How has the evolving political landscape impacted the development of Jakarta’s waste management and illustrated the inequalities of access to sanitation services?

To understand the broader waste management system in Jakarta, this report will define waste management as sanitation measures that can be separated into two parts: water supply and treatment and garbage collection. The city’s waste management is evaluated in four sections. First, I provide a brief history of Jakarta’s water supply network and its connection with its sewer development system. Second, I discuss the city’s garbage collection and disposal over the past four decades. Third, I focus on Indonesia’s decentralized political landscape and its impact on public sanitation services. Lastly, I address the relationship between government responsibility and the effects of waste management on poor and marginalized communities.

Water supply and sewage management

In 1619, the Dutch established Batavia, a walled colonial settlement that separated the wealthier neighborhoods of Europeans and other elites from the informal kampung villages of the indigenous populations (Putri 2009, 807). In delineating the boundaries between the two areas, the Dutch provided drastically different sanitation measures, such as water supply. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, a small percentage of households within the walled European settlement received piped water, which reduced the rate of water-borne diseases. However, Dutch authorities assumed that indigenous populations preferred using water in public spaces, so they did not provide them with household connections to water pipelines (Putri 2009, 810). The Dutch attitude towards planning water pipelines between European and local neighborhoods during the colonial period later translated into the inequitable distribution of sanitation services between upper and lower socioeconomic classes post-independence in Indonesia.

In the 2000s, high-income Jakartans actually disconnect their household’s municipal water connection due to unreliable water supply; instead, they pay for private piped water through their housing estate management, receiving water from deep, confined groundwater wells (Furlong and Kooy 2017, 897). Without the financial contributions of weather households, the cost of operating and upgrading the city’s municipal water network becomes less attractive (Furlong and Kooy 2017, 898). As a result, there was no incentive for the government to prioritize the expansion of the water supply network. It is interesting to note that while wealthier households have the option of connecting to the municipal water supply, they opt to disconnect. In contrast, low-income households are often without access to municipal water and resort to paying for bottled water or water from neighbors with a household water connection (Furlong and Kooy 2017, 898).

Jakarta’s water supply and wastewater and sewage treatment networks are heavily interconnected. Even though the water is safe to drink after leaving the water treatment plant, varying levels of water pressure in the water supply network can cause wastewater to contaminate the potable water (Furlong and Kooy 2017, 895). In 2015, Jakarta had approximately 1,852 households, accounting for less than 2 percent of the city’s population, connected to a central sewer system. (Nasution 2016, 68). Since wealthier households used septic and holding tanks for human waste, the city government has not expanded a centralized sewage system (Nasution 2016, 35). According to Cahyadi et al. (2021), existing septic systems do not meet technical requirements and actually contribute to the pollution of groundwater. (Cahyadi et al. 2021, 2). By strengthening both water supply and sewage management systems, Jakarta can significantly improve water quality and decrease water pollution.

Garbage and waste collection

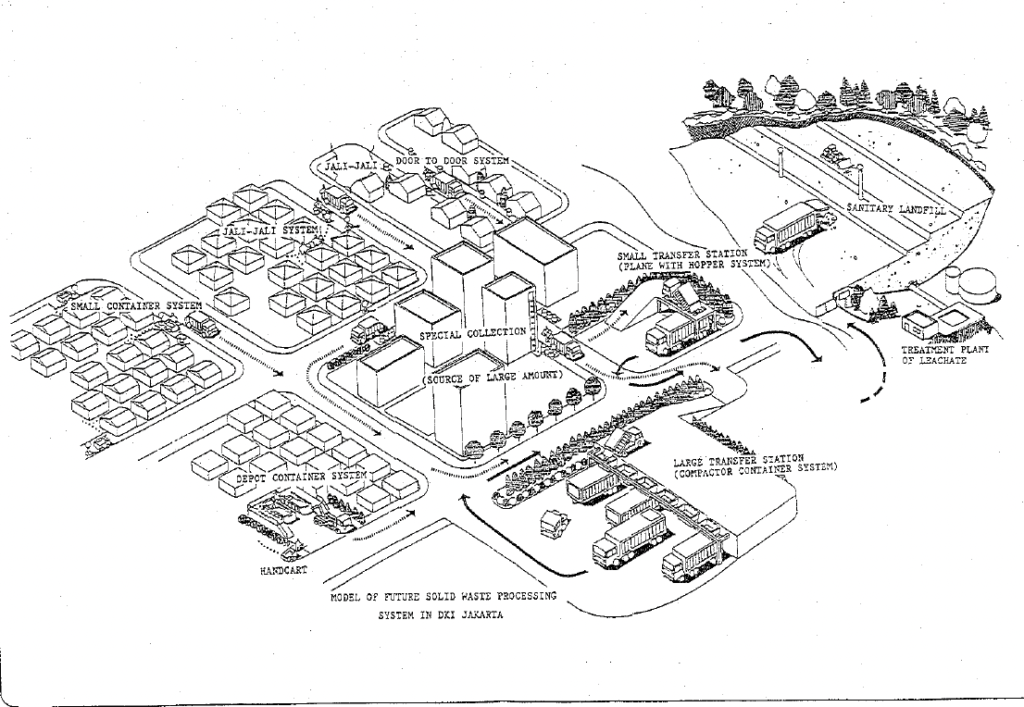

Garbage collection and disposal was also a huge challenge for rapidly urbanizing Jakarta in the twentieth century. By the 1980s, over 85 percent of all waste collection in Jakarta was done by handcart. The collected waste would then get transported to a temporary landfill and finally to a municipal landfill, an unauthorized open dumpsite, or incinerator. However, untreated waste in open dumpsites are hazardous and can pollute nearby water sources. As a result, the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) compiled a solid waste management proposal in 1987 for the establishment of two controlled, sanitary landfills in Bekasi and Tangerang, two locations outside of Jakarta’s city center, as part of new streamlined waste collection system (Study on Solid Waste 1987, 17-22). JICA suggested sanitary landfills as an affordable and feasible option to sustain a basic solid waste management system (Study on Solid Waste 1987, 17).

In the proposal, waste would be collected from households and businesses via handcart or other methods and then transported to an intermediary transfer station, where the waste would be re-sorted and transported to a waste treatment center before being dumped in a sanitary landfill (see Figure 1). Ideally, the newly proposed waste management system would reduce water pollution and illegal waste dumping in uncontrolled landfills.

Despite JICA’s thorough project proposal on improving Jakarta’s waste management system, the plan and its subsequent revised plans were never fully implemented (Putri 2009, 817). The decentralized government structure made prioritizing a comprehensive waste management system a significant hurdle to overcome. Furthermore, the general public have tended to perceive waste collection and sanitation services to be an individual household responsibility, which leads to a general unwillingness to pay for neighborhood waste management fees (Nasution 2016, 75). With the lack of both political urgency and public support, there is no immediate pressure to prioritize sanitation spending (Nasution 2016, 109). This also resulted in the unintended dearth of sanitation engineers in Indonesia. There are low numbers of sanitation engineers and their education was primarily based on Western city models, rendering them unable to transfer learned knowledge to the local Jakarta context (Nasution 2016, 41).

Government decentralization and its impact on sanitation

As Nasution concludes, there is a lack of literature in English on the development of Jakarta’s sanitation infrastructure. Consequently, it remains difficult to piece together a cohesive trajectory of the city’s municipal sanitation in relation to the evolving political landscape locally and nationally (Nasution 2016, 3). However, she cites the fragmented historical development of Jakarta’s water network to indicate the continual absence of centralized sanitation services (Nasution 2016, 3).

When Indonesia transitioned from an authoritarian government towards more democratic governance in the 1990s, the public expected that decentralization policies would bring additional government transparency and accountability, leading to more effective use of public funds for services like sanitation (van Voorst 2016, 5). In theory, the national and provincial governments were responsible for the initial costs of installing a waste management system while local governments were tasked with maintaining and financing the operations of the system (Chaerul et al. 2007, 41). However, decentralization led to varying results across different municipalities in Jakarta. Van Voorst cites the poor coordination of power and resources between local and national governments as a design flaw for local governance van Voorst 2016, 5). In 2007, Government Regulation No. 38 finally clarified the responsibilities of the central, provincial, and local governments (Firman 2008, 285).

Impacts of decentralization and government oversight

Interestingly, multiple pieces of literature did not attribute the lack of a waste management infrastructure to the lack of funding. Instead, the authors pointed to the lack of political commitment from the authorities as the main cause for the lag in development (Pasang 2007, 1936). Pasang believes that political commitment for improving waste management would allow for great visibility of government sanitation initiatives (Pasang 2007, 1936). Pasang goes further and argues that the Indonesian government should prioritize improving sustainable waste management since “the immediate issues are not greenhouse gases or the ozone layer but rather lack of proper amenities for water, sanitation, and safe haven” (Pasang 2007, 1929). Without adequate government oversight, Pasang asserts, waste disasters like the deadly 2005 waste avalanche in Bandung are likely to occur on a regular basis.

In the case of the Leuwigajah dumpsite in Bandung, a nearby city on Java Island, the landfill caused the world’s second deadliest waste avalanche in February 2005, killing 143 people (Lavigne et al. 2014, 2). After investigation, researchers concluded that heavy rainfall and biogas explosions were the cause of the waste avalanche. Biogas explosions occur in landfills with untreated waste. Leachate, toxic liquids that are extracted from solid waste, were not treated properly before waste disposal and resulted in the dangerous release of biogases (Lavigne et al. 2014, 11). Interestingly, the Leuwigajah dumpsite is officially categorized as a controlled landfill, but its eventual shift into an uncontrolled open dumpsite signifies the lack of government oversight surrounding waste management (Lavigne et al. 2014, 5). While the fatal accident in 2005 occurred outside of Jakarta, unregulated dumping can also result in similar consequences for dumpsites in the Jakarta metropolitan area if left uncontrolled.

Although there is a plethora of literature on improving Jakarta’s waste management infrastructure, there is a lack of discussion on the feasibility of a centralized approach in the context of Jakarta’s historical development. While the end goal of the development trajectory for waste management is a centralized sewer network and efficient landfill system for other cities, another model of waste management could be better suited for Jakarta’s history of fragmented sanitation development.

For instance, research on waste management should also consider scavengers in infrastructure development. Scavenger communities that live near the base of landfills are most vulnerable to waste avalanches (Lavigne et al. 2014, 9). Often overlooked in waste management planning, scavengers generally reside in housing built from scrap materials found onsite (Lavigne et al. 2014, 10). Despite the perception of a bottom-up approach from Indonesia’s decentralization, van Voorst argues that the technocratic approach of decentralization ignores the informal ways that marginalized groups interact with sanitation networks (van Voorst 2016, 6). Future advances in waste management in Jakarta should include consequences and solutions not just for privileged households but also scavenger communities and their possible displacement.

Bibliography

Aprilia, Aretha, Tetsuo Tezuka, Gert Spaargaren. 2011. “Municipal Solid Waste Management with Citizen Participation: An Alternative Solution to Waste Problems in Jakarta, Indonesia.” In Zero-Carbon Energy Kyoto 2010: Proceedings of the Second International Symposium of Global COE Program, Kyoto, 56-62. Springer.

Aprilia, Aretha, Tetsuo Tezuka, and Gert Spaargaren. 2012. “Household Solid Waste Management in Jakarta, Indonesia: A Socio-Economic Evaluation.” In Waste Management – An Integrated Vision. 72-100, IntechOpen. DOI: 10.5772/51464.

Cahyadi, Rusli, Dwiyanti Kusumaningrum, Sanusi and Ali Yansyah Abdurrahim. “Community-based sanitation as a complementary strategy for the Jakarta Sewerage Development Project: What can we do better?” E3S Web of Conferences 249 (2021): 1-6. DOI: 10.1051/e3sconf/202124901003

Chaerul, Mochammad, Masaru Tanaka, Ashok V. Shekdar. “Municipal Solid Waste Management in Indonesia: Status and the Strategic Actions.” Journal of the Faculty of Environmental Science and Technology – Okayama University 12.1 (2007): 41-49.

Furlong, Kathryn and Michelle Kooy. “Worlding Water: Thinking Beyond the Network in Jakarta.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41.6 (2017): 888-903. DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12582

Firman, Tommy. “In Search of a Governance Institution Model for Jakarta Metropolitan Area (JMA) Under Indonesia’s New Decentralisation Policy: Old Problems, New Challenges.” Public Admin. Dev. 28 (2008): 280-290.

Hadiwinoto, Suhadi, Josef Leitmann. “Jakarta. Urban Environmental Profile.” Cities 11.3 (1994): 153-157.

Lavigne, Frank, Patrick Wassmer, Christopher Gomez, Thimoty A Davies, Danang Sri Hadmoko, T Yan W M Iskandarsyah, JC Gaillard, Monique Fort, Pauline Texier, Mathias Boun Heng, Indyo Pratomo. “The 21 February 2005, Catastrophic Waste Avalanche at Leuwigajah Dumpsite, Bandung, Indonesia.” Geoenvironmental Disasters 1.10 (2014). DOI: 10.1186/s40677-014-0010-5.

Nasution, Nur ‘Aisyah. “The Dynamics of Piped-Water and Sewer Development in Jakarta, Indonesia (1945-2015): A Case Study Using Multilevel Perspective.” Master’s Thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2016.

Pasang, Haskarlianus, Graham A. Moore, Guntur Sitorus. “Neighbourhood-based waste management: A solution for solid waste problems in Jakarta, Indonesia.” Waste Management 27 (2007): 1924-1938. DOI: 10.1016/j.wasman.2006.09.010.

Putri, Prathiwi Widyatmi. “Sanitizing Jakarta: Decolonizing planning and kampung imaginary.” Planning Perspectives 34.5 (2009): 805-825.

Study on Solid Waste Management System Improvement Project in the City of Jakarta in Indonesia. Final Report Summary. n.p. Japan International Cooperation Agency, 1987.

Van Voorst, Roanne. “Formal and informal flood governance in Jakarta, Indonesia.” Habitat International 52 (2016): 5-10. DOI: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.08.023.

Feature header image credit: By Midori – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17242025