Cristian Gonzalez

Questions

What have been the differences between public waste management and private waste management in Bogota? What are the roles of scavengers in Bogota in the waste management industry?

Discussion

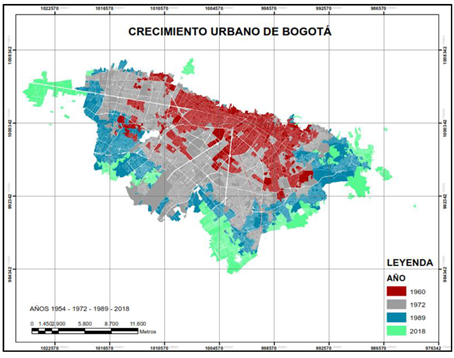

As expected, the bigger the city, the greater the waste production. The rapid growth of the city, which grew from 1,172 hectares in 1928 to 30,041 hectares in 2000 (see Figure 1), and the inefficiency of the local government of Bogota to clean up the city for most of the 1900s, worsened waste management in Bogota (Molano 2019a: 28-31). In 2018 Bogota’s daily production of waste was 6,800 tons, compared to 450 produced in 1950 (Molano 2019a: 4). From that total of waste, as illustrated by Padilla and Trujillo, 52% of the total waste is produced by households and 42% from manufacturing, by which 60% of waste related to human activity is organic waste (food) following by plastic (10%) (19). In the international context, for instance, the household characterization of waste in Ghana is similar to Bogota in which organic waste and plastic are the most generated wastes (19). Undoubtedly, this is a huge amount of waste to be managed, and according to Piña and Martinez, 80% of the 2.4 million tons produced yearly is going to the only landfill in Bogota, called Doña Juana (37). In historic context, according to Molano (2019a), from the 1950s Bogota has used two different models to manage the waste in the city (3): the developmental model (1950 to 1988) in which the state plays the main role, and the neo-liberal model (1988) in which the private sector is the main actor (3).

Figure 1. Urban growth of Bogota (1960-2018). Molano 2019a

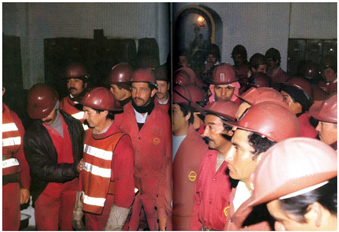

Molano’s doctoral thesis in history analyzes the historic waste policies from 1950 to 2019 in Bogota. Molano divided waste management in Bogota in two models: the developmental model, from 1950 to 1988, and the neoliberal model, from 1988 to the present. The developmental model, which started in 1950, was influenced by the Pan-American Health Organization (OPS) and the World Bank in a global effort to tackle the waste problem in cities around the world (35). These capitalist policies, as Molano states, were focused on the public sector as the main actor to solve social issues, encouraging governments to create public companies, such as the sanitation company of Bogota (42). This developmental model was based on: (1) manual labor, since 90% of the trash collection was done by people sweeping the streets, (2) trucks that collected the garbage from households, and (3) trash cans in some spots in the city (47). In 1965, 90% of the street waste was collected by more than 800 street cleaners, and the remaining 10% was collected by rubbish collection trucks (47). These street sweepers usually were low-income people, not much respected by society, and sometimes referred to with pejorative nicknames, such as pigs (51). In an effort to improve the image of the street cleaners, in the 1970s, the sanitation office implemented different strategies such as dressing the staff in uniforms, creating new logos for the company, and introducing new positive nicknames such as “escobitas”, which means “tiny sweepers” (Figure 2) (51).

Figure 2 Escobitas in the 1970s in Bogota. Molano 2019a

Despite these waste-management efforts, the size of the problem was very much greater than the sanitation company’s capacity. In 1980 the city was daily producing 4,500 tons of waste, and the company was collecting 2,000 tons, so the remaining 56% were left on the streets, frequently creating sanitary emergencies. Even though the sanitation company greatly increased the work of the escobitas to collect the garbage left on the streets, in the end, the public company solved these sanitary emergencies hiring private trucks to collect the remainder trash, rising questions about the relevancy to privatize the sanitation company (Molano 2019a: 57-58). Clearly, the developmental model was failing. Molano points out some reasons. First and most important is that politicians traded jobs for votes and personal favors, affecting the efficiency of workers because the supervision of the workers’ performance became almost impossible, since each worker had a political godfather (60). Second, the city council did not give the sanitation company the necessary annual budget to cope with the growing volume of waste in Bogota (60).

The developmental model discouraged the tradition that low- and middle-income households had to recycle (Molano 2019a: 87). According to Molano, the initial intention was the introduction of trash cans to households to ease the collection of waste for the sanitation staff, hoping that the households’ women would stop their tradition of separating paper, glass, cans, and cardboards to sell them to the scavengers. This informal recycling from households to scavengers was seen as unfair competition by the sanitation staff, in part because there were some private contractors who were paid by ton collected (87). Thus, the city waste service encouraged households to gather both recyclable and non-recyclable trash in the same can, claiming it made for more efficient and economical service (88).

Figure 3. Scavengers in Bogota. Beltran Granados, Maria Camila, “Movilidades marginales: viajes y experiencias de los recicladores de Bogota” Universidad Nacional de Colombia (2018)

Stefania Gallini notes that scavengers worked on their own, carrying the waste in handcarts or horse-drawn carts to the market (Figure 3). As mentioned earlier, they directly made deals with housewives and janitors to get their recycled materials to later sell to factories and supermarkets in the formal market (70). Additionally, many of these scavengers worked and lived in the two waste-dumps of the city, called Gibraltar and Cortijo (Rosaldo 2016: 362). These waste-dumps increasingly were creating health issues for the city, even causing typhoid epidemics in neighborhoods around the dumps because of the frequent garbage fluids during the rain seasons (Molano 2019a).

Manuel Rosaldo describes the most important mobilizations for labor rights of informal recyclers as a response to their extreme poverty. Rosaldo also states the rise of neoliberalism and the consolidation of democracy as positive factors that helped scavengers to raise their voices to fight for their rights because of strong institutions such as the Constitutional Court of Colombia. As Rosaldo describes in the second half of the 1980s, the Gibraltar and the Cortijo dumps were closed, leaving scavengers without their income source and a place to live (360-364). These displaced scavengers were pushed to work on the streets, in places where they had never shown up before, causing a negative response from many people who did not like the scavengers’ presence in their neighborhoods and resulting in a wave of violence against these vulnerable people (363). These violent attacks against the scavengers, as Rosaldo states, attracted sympathy from university students, NGOs, and other people, who helped scavengers to create associations in order to better respond to the threats and at the same time increase their incomes (364).

Later on, in 1990, the three scavengers’ associations joined together to create the famous Asociacion de Recicladores de Bogota (ARB). As Rosaldo illustrates, their intention was to turn their recycling activity into a respectable profession with better incomes, gaining political recognition (357). The ARB and other Colombian recycling associations together have achieved at least eight victories in the Constitutional Court of Colombia since 2003, obtaining rights and reversing government policies that threatened their livelihoods. One of these reversed policies was a presidential Decree that had declared all waste on the street to be property of the waste company operator of the area, potentially targeting recyclers as thieves (365). Another Constitutional Court victory was their formal inclusion in the private business of waste (365). Even though the implementation of those rights has been slow, and many of these recyclers remain with low-incomes and in many cases in extreme poverty, in the year 2014, both the informal and the associated recyclers collected 300 tons daily. In other words, 300 tons less waste went to the landfill daily (Martinez and Piña 2016: 1075). However, Martinez and Piña estimate that the daily potential volume of waste that can be recycled in Bogota is 1000 tons, so there are still lots of economic opportunities for scavengers (1075).

A product of the discrediting of the developmental model is that the neo-liberal model was born. During the 1980s, the capitalist approach changed from the public sector as a protagonist to the private sector and free market as the main actor. As Molano states, to privatize the waste management of Bogota, the local government blamed unions as the cause of the inefficient companies because of the high requirements of benefits to the employees and the lack of supervision of their performance, allowing low performance in workers without many consequences (162-166). However, Molano explains that unions were only the tip of the iceberg of the public companies’ inefficiency because the biggest problem was the excessive clientelism between the state and the people. In other words, politicians traded off jobs for personal favors, not always allocating the most qualified people in public companies. Despite many strikes by escobitas, who were the most vulnerable part of the equation, the company was privatized.

The neo-liberal model was carried out coinciding with the implementation of a new model of waste management based on the landfill as a new method to gather the waste in the city (Molano 2019b). This landfill is called Doña Juana (DJL) and was planned to replace the past two waste-dumps. The DJL initially was expected to last until the year 2000, and it started with an area of 50 hectares (Molano, 2019b:138). Nevertheless, today DJL is still active and is the only landfill in Bogota, with 600 hectares in the south of the city (Molano, 2019b:138). This landfill has had many environmental and technical troubles, first because the landfills that existed in the US and Europe in the 1980s were small and middle sizes, and the size of DJL was many times larger than those landfills around the world, making it very difficult to find experts to share their knowledge (Molano, 2019a: 207). This landfill was considered an experiment because of its size, but there were consequences, such as the landslide that occurred in 1997, in which more than one million tons of garbage collapsed inside the DJL, causing odors over an area of one mile, and creating a sanitary emergency in the south of Bogota (Molano, 2019a: 206).

Figure 4. Doña Juana landfill. htpp://www.personeriabogota.gov.co/sala-de-prensa-/notas-de-prensa/item/643-dona-juana-sigue-relleno-de-irregularidades

Unlike the old dumps, from the beginning the DJL did not allow the entrance of the scavengers. The new private waste management continued ignoring scavengers despite their stronger position because of the associations (Molano 2019a: 209). This occurred because the private companies were paid per ton disposed in the landfill, so they were interested in collecting as much garbage as possible (210-2015). Thus, like the developmental model, the neo-liberal model does not recycle at all. The original idea to privatize the waste management of Bogota was allowing free competition over waste services and prices, bringing as many companies as possible to the business. Nonetheless, as Molano describes, the same four or five multinational companies have been managing the waste in Bogota, contrary to the initial plan (192). Additionally, the new escobitas (street cleaners) lost the benefits that were obtained by unions in the past, such as job stability and better incomes. Another of Molano’s criticisms of the neo-liberal model is that the private companies lack responsibility for the environmental or physical damage related to waste management, as evidenced in the aftermath of the 1997 landslide at DJL. After this huge landslide, though the Mayor of Bogota terminated the contract with the DJL administrator, the local government had to compensate the company for the abrupt termination, in addition to repairing the landfill, and to compensate more than 60,000 people affected in the accident. In sum, the local government had to pay more than $100 million (Molano,2019b:143).

Padilla and Trujillo identify the factors that shape the attitudes towards source separated recycling among the different social classes in Bogota. In the year 2000, as Padilla and Trujillo note, Bogota started the implementation of “The Integrated Solid Waste Management Master Plan (PMIRS)”, aiming for the reduction of waste production in the city through different policies (19). However, Padilla and Trujillo illustrate that the DJL still in the year 2004 had serious environmental issues, such as the proliferation of odors, rodents, and flies, severely affecting the surrounding communities (19). Therefore, not much had changed since the 1990s regarding environmental issues in the only landfill of Bogota. Continuing with the waste reduction goals, in 2012 the Mayor of Bogota launched the zero-waste program, an ambitious effort to reduce the city’s waste production by 30% in a four-year period, through policies such as formalizing the total number of recyclers in the city and rolling back to the developmental model, but in 2015 the reduction of waste achieved was only 3.2% (Padilla and Trujillo 2018: 19; Gallini 2016).In the end, the neo-liberal model improved the coverage of waste service, reaching 100% of the city, and substantially decreased citizen complains. However, the local government did not supervise the companies sufficiently, allowing constant increases in bills, and few consequences when things go wrong, as seen in the 1997 DJL landslide. In sum, due to the growing social recognition of the importance of recycling in Bogota , in the last few years the scavenger’s recognition also has significantly improved.

SOURCES:

Beltrán, María Camila Granados. “Movilidades marginales: viajes y experiencias de los recicladores de Bogotá.” Universidad Nacional de Colombia (2018).

J. Padilla, Alcides, and Juan C Trujillo. “Waste Disposal and Households’ Heterogeneity. Identifying Factors Shaping Attitudes Towards Source-Separated Recycling in Bogotá, Colombia.” Waste Management (Elmsford) 74 (2018): 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2017.11.052.

Manuel Rosaldo. “Revolution in the Garbage Dump: The Political and Economic Foundations of the Colombian Recycler Movement, 1986-2011.” Social Problems (Berkeley, Calif.) 63, no. 3 (2016): 351–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spw015.

Molano Camargo, Frank. 2019 a. “Las políticas de la basura en Bogotá: Estado, ciudadanía y derecho a la ciudad en la segunda mitad del siglo XX.” PhD diss., Universidad de los Andes, 2019.

Molano Camargo, Frank. 2019 b. “El relleno sanitario Doña Juana en Bogotá: la producción política de un paisaje tóxico, 1988-2019.” Historia crítica (Bogotá, Colombia), no. 74 (2019): 127–49. https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit74.2019.06.

Stefania Gallini. “The Zero Garbage Affair in Bogotá.” RCC Perspectives, no. 3 (2016): 69–78.

Pardo Martinez, Clara Ines, and William Alfonso Pina. “Solid Waste Management in Bogota: The Role of Recycling Associations as Investigated through SWOT Analysis.” Environment, Development and Sustainability 19, no. 3 (2017): 1067–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-016-9782-y.